Sexual vs Asexual Population Growth Calculator

Calculate Evolutionary Population Growth

See how sexual reproduction compares to asexual reproduction over generations based on Maynard Smith's two-fold cost theory.

| Generation | Asexual Population | Sexual Population | Relative Growth |

|---|

Understanding the Two-Fold Cost

As you can see, asexual reproduction doubles population each generation, while sexual populations grow at a slower rate due to the two-fold cost. The key insight is that despite the initial disadvantage, sexual reproduction provides long-term evolutionary advantages that overcome this cost:

- Muller's ratchet: Sexual reproduction eliminates harmful mutations

- Red Queen hypothesis: Sexual populations resist parasites better

- Faster adaptation to changing environments

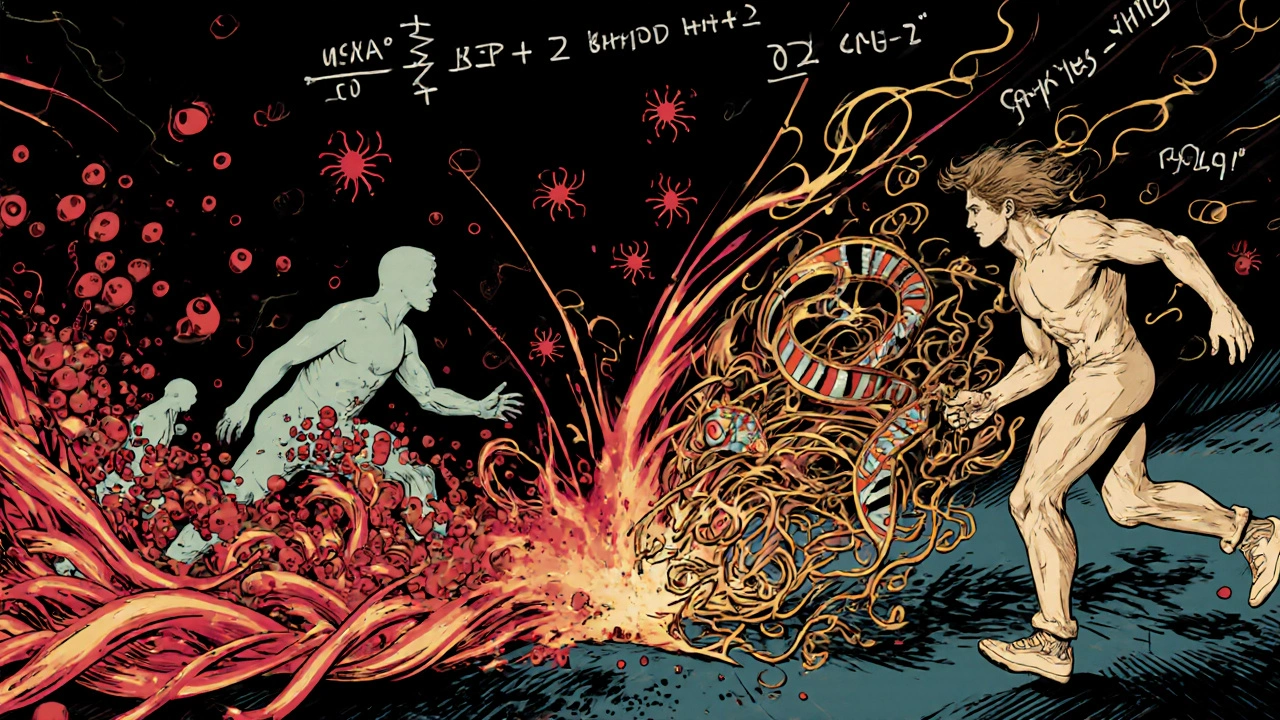

Imagine a world where every organism reproduces alone. No mates, no courtship, no males - just females cloning themselves perfectly, generation after generation. In this world, each female produces two offspring, and both of those offspring are also females who can reproduce right away. After one generation, the population doubles. After two, it quadruples. Simple. Efficient. Sexual reproduction, by contrast, is messy. Half the offspring are males - and males don’t give birth. In a population with equal numbers of males and females, only half the individuals directly produce the next generation. That means, mathematically, sexual populations grow at half the speed of asexual ones. So why does sex exist at all?

The Two-Fold Cost of Sex

This isn’t just a thought experiment. In 1971, British biologist John Maynard Smith laid out the math clearly: sexual reproduction carries a two-fold cost. If asexual females produce two offspring, and all of them are female and can reproduce, then each asexual lineage grows at double the rate of a sexual one. In sexual populations, each female still produces two offspring, but one is male. That male doesn’t make babies himself. He just carries genes. So, per female, the reproductive output is cut in half. That’s the two-fold cost - and it’s real.Field studies confirm it. In New Zealand, scientists studied a freshwater snail called Potamopyrgus antipodarum, which has both sexual and asexual populations living side by side. Over 18 months, researchers tracked over 3,400 snails. They found that asexual females produced nearly twice as many grand-offspring as sexual females - 1.98 times more, to be exact. The numbers matched Maynard Smith’s prediction almost perfectly. In stable environments, asexual reproduction should win. It’s faster. It’s simpler. It doesn’t waste energy on males.

Why Don’t Asexuals Take Over?

If asexual reproduction is so much more efficient, why haven’t all animals and plants gone that route? The answer lies in what happens over time - not in the short term, but over hundreds or thousands of generations.Asexual populations are genetic clones. Every offspring is a perfect copy of the mother. That sounds great - until mutations pile up. Every generation, random errors creep into DNA. In asexual lineages, those errors stick around forever. There’s no way to fix them. This is called Muller’s ratchet. Imagine a ratchet that only turns one way: each mutation adds another click, and you can’t go back. Over time, the genetic load builds up. The population gets weaker, less able to survive.

Sex breaks that cycle. When two parents mix their genes, they create new combinations. Harmful mutations can be masked, shuffled out, or eliminated. A 2015 study in PLOS Genetics found that sexual species carry 17.3% fewer harmful mutations than their asexual relatives. That’s not a small edge - it’s life or death over time.

The Red Queen and the Parasite Arms Race

There’s another big reason sex survives: parasites. Think of it like a never-ending race. Parasites evolve fast. They adapt to infect the most common host types. In an asexual population, everyone is genetically identical. If a parasite finds a way to infect one individual, it can infect them all. That’s a population killer.Sex changes the game. By mixing genes every generation, sexual populations produce offspring with new immune defenses. It’s like constantly changing your lock so the burglar can’t pick it. This idea is called the Red Queen hypothesis - named after the character in Alice in Wonderland who says, “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

In New Zealand lakes, researchers found that sexual Potamopyrgus snails were 2.2 times more resistant to a deadly parasitic worm than their asexual cousins. In labs, when nematodes were exposed to bacteria, sexual lines outperformed asexual ones by 34% after just 30 generations. The more parasites in the environment, the more sexual reproduction dominated. When parasites were removed, asexuals bounced back. Sex isn’t always better - but it’s better when things are changing.

When the Cost Isn’t Two-Fold

The classic two-fold cost assumes a 50-50 split between males and females. But nature doesn’t always follow the rules. In some species, sex ratios are skewed. A 2016 study on onion thrips found that in sexual populations, 67% of offspring were female. That cuts the cost down to about 1.5-fold. In fig wasps, males rarely leave their birth site - they mate with sisters and die young. The cost of producing them is tiny. In these cases, sex doesn’t need a huge benefit to stick around.Even in species with equal sex ratios, not all males are equal. In some fish, males don’t raise young. They just fertilize eggs and leave. The energy cost of making a male is low. In mammals, males take more resources - but in birds, males often help feed chicks. The cost of sex isn’t fixed. It’s flexible. And that flexibility helps explain why sex is so widespread.

Genetic Mixing Is a Long-Term Survival Tool

Sex isn’t about efficiency. It’s about resilience. Asexual reproduction is like using the same password for every account - it works until it doesn’t. Sexual reproduction is like changing your password every week. It’s annoying. It takes effort. But it keeps you safe.Studies show sexual populations adapt 60% faster to environmental changes than asexual ones. In a changing climate, new diseases, or shifting food sources, the ability to shuffle genes gives sexual species a huge advantage. Even small benefits - like a 1% increase in survival chance - can outweigh the two-fold cost over hundreds of generations. Evolution doesn’t care about speed. It cares about staying alive long enough to pass on genes.

And that’s the key point: sex isn’t about winning the next generation. It’s about winning the next hundred.

Why We Still Don’t Have All the Answers

Despite decades of research, the puzzle isn’t fully solved. Some scientists argue that the benefits of sex are too small to justify the cost. Others say the cost is often overstated. A 2020 paper found that the genetic advantage from recombination might be as low as 0.1% per generation - barely enough to matter. But then again, when you combine that with parasite resistance, mutation cleanup, and faster adaptation, the numbers add up.What’s clear is that sex isn’t a single trick. It’s a toolkit. Muller’s ratchet fixes mutations. The Red Queen fights parasites. The Fisher-Muller effect speeds up adaptation. And in some cases, even the cost itself gets reduced by biased sex ratios or low male investment.

There’s no one reason sex survived. There are many. And together, they outweigh the cost.

Sex Isn’t a Flaw - It’s a Strategy

We often think of evolution as a race to the fastest, strongest, most efficient. But evolution doesn’t reward efficiency. It rewards survival. And in a world full of parasites, mutations, and change, sex is the ultimate insurance policy.Asexual reproduction might win in a quiet, stable pond. But in the messy, dangerous, ever-changing world outside - where predators, pathogens, and climate shift constantly - sex is the only strategy that lasts.

It’s not about having more kids today. It’s about having kids who can survive tomorrow.

What is the two-fold cost of sex in evolution?

The two-fold cost of sex refers to the fact that in sexually reproducing species with a 1:1 sex ratio, only half the population (females) directly produce offspring, while the other half (males) do not. This means asexual females - who produce only female clones - can double their population each generation, while sexual populations remain stable. As a result, sexual reproduction appears to have half the reproductive efficiency of asexual reproduction.

Why hasn’t asexual reproduction replaced sexual reproduction if it’s more efficient?

Although asexual reproduction is faster in the short term, sexual reproduction provides long-term genetic advantages. It helps eliminate harmful mutations through recombination, speeds up adaptation to changing environments, and improves resistance to parasites. These benefits outweigh the immediate cost over many generations, especially in complex or unstable ecosystems.

How does the Red Queen hypothesis explain the persistence of sex?

The Red Queen hypothesis suggests that sex persists because it helps hosts stay ahead of rapidly evolving parasites. Asexual populations are genetically identical, so a parasite that adapts to infect one individual can infect them all. Sexual reproduction constantly reshuffles genes, creating new combinations that parasites haven’t seen before. Studies on snails and nematodes show sexual populations resist infection significantly better than asexual ones in parasite-rich environments.

Is the two-fold cost the same in all species?

No. The cost depends on sex ratios, how much energy is invested in males, and environmental conditions. In species with female-biased sex ratios - like onion thrips - the cost drops below two-fold. In species where males contribute little to offspring care, the cost is lower. In high-predation or parasite-heavy environments, sexual females may even have higher offspring survival, making the cost disappear entirely.

Can asexual species survive long-term?

Some asexual species survive for thousands of years, like certain lizards and insects. But they’re rare in complex ecosystems. Most asexual lineages go extinct quickly because they accumulate harmful mutations and can’t adapt to new threats. The few that last often live in stable, isolated environments where parasites and competition are minimal.

What evidence supports the benefits of sexual reproduction?

Multiple studies confirm the benefits. In Potamopyrgus snails, sexual females had 23% higher fitness in parasite-rich environments. In nematodes exposed to bacteria, sexual lines showed 34% higher fitness after 30 generations. Genomic studies show sexual species carry 17.3% fewer harmful mutations. Experiments with rotifers show sexual populations adapt 60% faster to environmental change. These aren’t theoretical - they’re measured in real organisms.