Golden Ratio Beauty Calculator

Ancient Greek sculptors used the Golden Ratio (1:1.618) to create ideal male forms. This calculator helps you understand how your proportions compare to this ancient standard.

Did you know? Greek kouros statues were designed with the Golden Ratio (1:1.618) to represent the ideal male form. This ratio was believed to reflect divine order and was used in sculpture, architecture, and philosophy to embody the concept of kalokagathia—the union of physical beauty and moral virtue.

When you think of ancient Greek art, you probably picture perfect marble statues-naked young men with broad shoulders, narrow hips, and calm, timeless faces. But these weren’t just decorations. They were political statements. Religious symbols. Social codes. And above all, they were the physical embodiment of kalokagathia-the Greek ideal that said a man’s beauty wasn’t just how he looked, but who he was.

What Kalokagathia Really Meant

This wasn’t a fantasy. It was the standard for Athenian citizenship. Only freeborn males could aim for it. Women, slaves, and foreign residents were excluded by law and custom. The men who embodied kalokagathia were called the kaloi k’agathoi-the beautiful and good ones. They weren’t just rich aristocrats. They were the ones who led armies, spoke in the Assembly, and taught the next generation.

Plato wrote that true beauty was the harmony of body and soul. Aristotle agreed. To them, a man who trained his body but ignored his mind was no better than a horse. And a man who read philosophy but couldn’t run a race? He wasn’t fit to lead.

The Body as a Public Project

In Athens, your body wasn’t private. It was performance art. Every morning, boys aged 12 to 18 trained in the gymnasia-public exercise yards where nudity was normal. You didn’t just lift weights or wrestle. You were being watched. Judged. Ranked.

The ideal male form? Tall, lean, muscular but not bulky. Narrow waist, broad shoulders. Symmetrical. Balanced. The kouros statues from the 600s BCE show this perfectly. They’re not portraits of real people. They’re mathematical ideals. Most stand nearly 2 meters tall. Their waist-to-shoulder ratio matches the Golden Ratio-1:1.618. That’s the same proportion found in shells, galaxies, and Renaissance paintings. The Greeks believed this wasn’t coincidence. It was divine order.

But here’s the twist: the average Athenian man was only 165 cm tall. Most of them were shorter, weaker, and scarred from labor. The statues? They were aspirational. They showed what a citizen should be-not what he was.

Youth as the Highest Form of Beauty

The most admired body wasn’t the mature soldier’s. It was the ephebe’s-the boy just past puberty, still beardless, still soft around the edges. Between 12 and 18, a young man was at his peak of physical beauty. That’s why so many vase paintings show older men admiring youths. This wasn’t just about lust. It was about potential.

The relationship between the erastes (the older lover) and the eromenos (the beloved youth) was a social institution. It wasn’t random. It had rules. The youth was expected to be modest. Not to seek pleasure. Not to appear eager. The older man was supposed to guide him-not exploit him. The goal? To turn physical attraction into intellectual mentorship.

Plato’s Symposium makes this clear. Socrates says the first step toward wisdom is falling for a beautiful boy. But the real goal? To rise above the body and see beauty itself-the kind that lives in ideas, justice, truth. Desire was the ladder. The body was just the first rung.

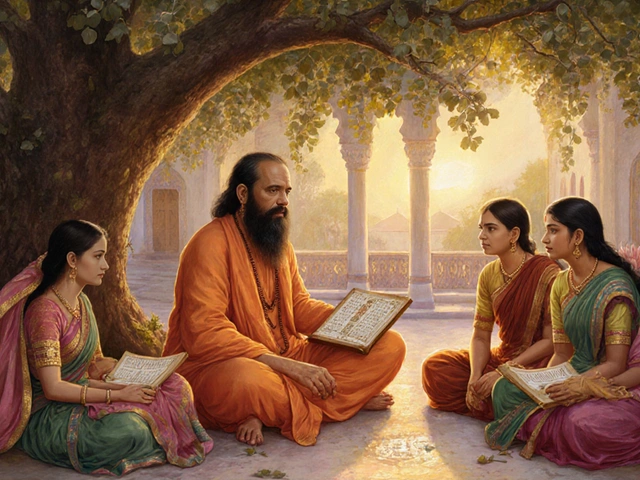

Education: The Making of a Man

Kalokagathia didn’t come from birthright alone. It was taught. From age seven, boys studied under two masters: the paidotribes (gymnastics trainer) and the kitharistes (music teacher). They ran, wrestled, threw discus. Then they played the lyre, recited Homer, learned rhetoric.

Why music? Because the Greeks believed rhythm and harmony shaped the soul. A boy who could play the lyre well was assumed to have self-control. One who could recite epic poetry understood honor, duty, sacrifice. These weren’t hobbies. They were moral training.

Archaeologists have found palaestras-wrestling schools-with viewing platforms. The architecture was designed so everyone could see the boys train. Beauty was on display. And display meant status. The better you looked, the more respect you got. The more respect you got, the more influence you had.

When Beauty Failed

But kalokagathia wasn’t foolproof. Alcibiades, one of Athens’ most beautiful and charismatic leaders, had it all-aristocratic blood, perfect physique, brilliant mind. Yet he was exiled, accused of sacrilege, and eventually killed. Why? Because he broke the code. He was ambitious. Self-serving. He used his charm to manipulate, not to uplift.

Plato saw this coming. In the Gorgias, he argues that real beauty comes from the soul. A man can look perfect and still be corrupt. That’s why the ideal was always under pressure. Society wanted the body to reflect the soul. But sometimes, it didn’t.

Even the statues tell the story. The earliest kouroi look stiff, almost robotic. Later ones, like the Kritios Boy, show movement, emotion, individuality. The Greeks were learning: beauty wasn’t just about perfection. It was about life.

Power, War, and the Phalanx

Kalokagathia wasn’t just about looks. It was about survival. In the hoplite phalanx, soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder, shields locked, spears forward. One weak link could break the line. And die. Everyone else.

That’s why fitness mattered. Not for vanity. For collective safety. A man who trained in the gymnasium wasn’t just preparing for beauty contests. He was preparing to die for his city. The same body that won admiration in the palaestra was the one that held the line at Marathon or Salamis.

Victor Davis Hanson calls this the "Western Way of War"-a system where civic duty and physical excellence were fused. You didn’t fight because you were told to. You fought because you were expected to. And if you weren’t fit? You weren’t a full citizen.

Who Got to Be Beautiful?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: kalokagathia was exclusive. Only about 10-15% of Athenians could fully participate. You needed money. Land. Freedom. Slaves did the work so citizens could train. Women? They were kept inside. They didn’t enter gymnasia. They didn’t study rhetoric. They didn’t vote. Even in Sparta, where women trained physically, they were still barred from the intellectual side of the ideal.

But here’s the twist: it wasn’t completely closed. Themistocles, the general who saved Athens at Salamis, wasn’t born noble. He rose through skill, strategy, and public service. His story proved that kalokagathia could be earned. Not just inherited. That’s why the ideal lasted. It gave people something to reach for.

The Legacy That Still Shapes Us

When Renaissance artists like Michelangelo sculpted naked men, they weren’t just copying Greek statues. They were reviving a philosophy. Leon Battista Alberti wrote in 1434 that a man must train his body and mind equally-just like the Greeks. When modern educators push "whole-person development," they’re echoing kalokagathia.

Martha Nussbaum, a contemporary philosopher, links it to her "capabilities approach"-the idea that human dignity requires access to health, education, and expression. That’s kalokagathia in 21st-century language.

Even our gym culture, our obsession with "getting fit," our belief that discipline equals virtue-those roots go back to Athens. We may not worship marble statues anymore. But we still believe that how you look says something about who you are.

Why This Still Matters

Kalokagathia wasn’t just about male beauty. It was about power. Who gets to be seen as valuable? Who gets to be heard? Who gets to lead?

Today, we’re still wrestling with the same questions. Is beauty a right? A reward? A performance? Can someone be morally good and physically ordinary? Can someone be gorgeous and broken inside?

The Greeks didn’t have easy answers. They argued about it. They painted it. They built statues to debate it. And maybe that’s the real lesson. Beauty isn’t a fixed standard. It’s a conversation. One that never ends.