Mattachine Society Knowledge Quiz

Test Your Knowledge

How much do you know about America's first gay rights movement? This quiz will test your understanding of the Mattachine Society, its history, and its impact on LGBTQ rights. Select the best answer for each question and see how you score.

In 1950, when being openly gay could cost you your job, your freedom, or even your safety, a small group of men in Los Angeles started something dangerous: a secret society to fight for their right to exist. They called it the Mattachine Society. Not a protest group, not a support circle - but a carefully organized movement built on secrecy, strategy, and the radical idea that homosexuality wasn’t a sickness, but a culture.

How a Secret Society Became a Movement

The Mattachine Society didn’t begin with marches or signs. It started in the living room of Harry Hay, a former Communist Party member and labor organizer, along with five other men: Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Dale Jennings, Konrad Stevens, and Rudi Gernreich. They met in silence, spoke in code, and never revealed their full names. Their model? The Communist Party’s cell structure - hidden leadership, strict loyalty, and layers of secrecy to protect members from the FBI, police, and employers who saw gay people as threats. They chose the name "Mattachine" after medieval French masked dancers who used theater to mock the powerful. It was perfect: invisible, symbolic, and defiant. Their first mission statement, written in April 1951, didn’t ask for tolerance. It demanded recognition. They compared themselves to Black, Mexican, and Jewish communities - all fighting for dignity in a society that treated them as less than human.Challenging the Medical Establishment

Back then, the American Psychiatric Association called homosexuality a "sociopathic personality disturbance." Doctors, judges, and politicians used that label to justify firing people, locking them up, or forcing them into "cures" like electric shock therapy. The Mattachine Society flipped the script. They didn’t try to prove gay people were "normal." They argued they were a minority group - with shared history, values, and experiences - just like any other. This wasn’t just theory. They printed pamphlets and sent them to doctors, lawyers, and clergy. By 1955, they claimed to have reached 75% of the nation’s leading psychiatrists. Their goal? To change the minds of the people who held the power to label, punish, or heal.The Jennings Case: When a Trap Backfired

In February 1952, Dale Jennings was arrested in a Los Angeles park on charges of "lewd behavior." It wasn’t a random arrest. Police routinely targeted gay men in public spaces, luring them into traps and then arresting them. The Mattachine Society didn’t stay quiet. They turned Jennings’ arrest into a public campaign. They hired a lawyer, raised money, and mobilized supporters. At trial, they challenged the police’s entrapment tactics. The jury couldn’t agree - a hung jury. One juror later said, "We’ve made up our minds that the police are the ones who are guilty." It was a tiny win, but in 1952, it was revolutionary. For the first time, a court didn’t automatically side with the state against a gay man. That case became the foundation of their legal defense network. If you were arrested, Mattachine helped you. They didn’t just offer lawyers - they gave people dignity.

The Great Shift: From Radical to Respectable

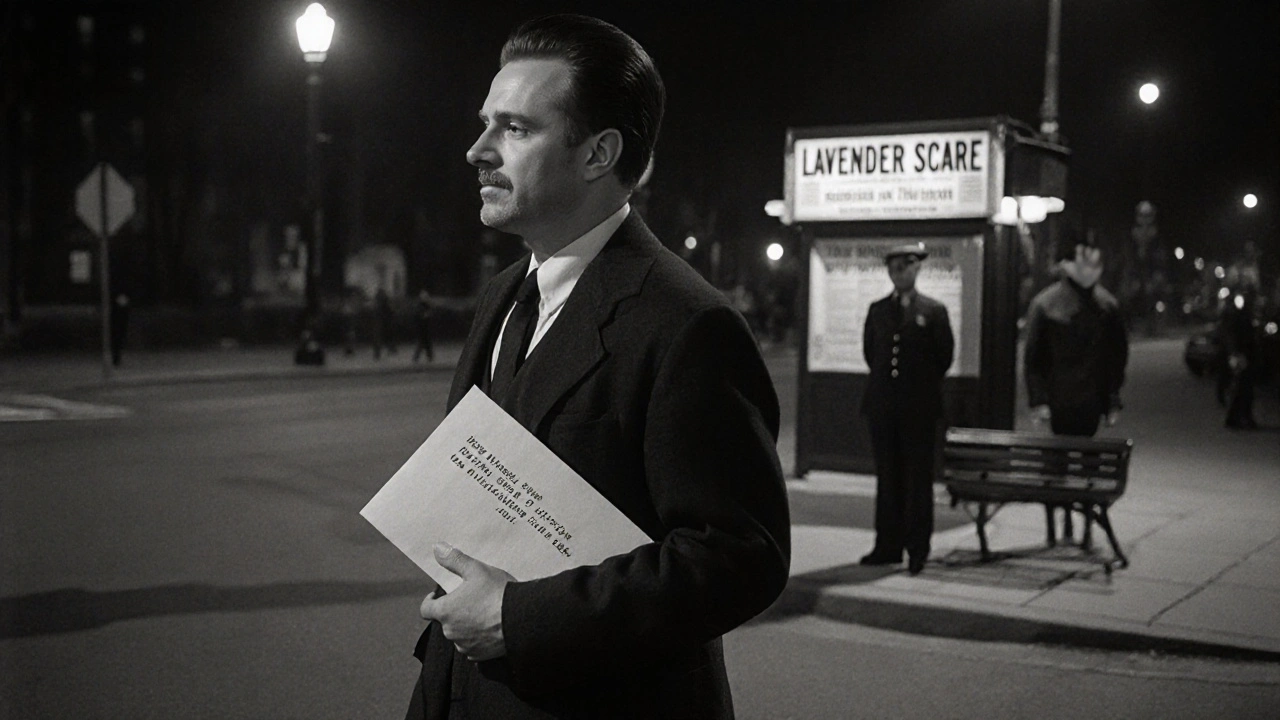

By 1953, the original founders were scared. McCarthyism was in full swing. The FBI was watching. The government was firing hundreds of gay federal workers under the "Lavender Scare." The leadership of the Fifth Order - the secret core of Mattachine - resigned. In their place came more conservative members like Hal Call and Ken Burns. The new leadership changed the rules. They banned "subversive elements" - meaning, no more Communists. They demanded loyalty to U.S. laws, even though those laws criminalized homosexuality. They dropped the idea of cultural liberation. Their new goal? Assimilation. Be quiet. Be respectable. Don’t make waves. This split changed everything. Membership dropped. The radical energy faded. But the organization didn’t die. It adapted.The Mattachine Review: Quiet Power

Even after the shift, they kept publishing. In 1955, they launched The Mattachine Review, a newsletter that reached about 2,000 readers by 1960. It wasn’t flashy. No photos. No bold headlines. Just essays, letters, and articles about gay life, law, and identity. It was distributed carefully - mailed in plain envelopes, never marked as "homosexual content." This was their weapon: education. They taught gay men they weren’t alone. They showed doctors that gay people weren’t sick. They proved that a quiet, persistent voice could change minds.Contrast: Mattachine vs. Daughters of Bilitis

In 1955, a parallel group formed: the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national lesbian organization. While Mattachine was mostly gay men, Bilitis focused on women. Both groups shared the same strategy: non-confrontation, education, respectability. But Bilitis was even more cautious. Their newsletter, The Ladder, avoided political language entirely. They didn’t challenge laws - they asked for understanding. Mattachine had more structure. More political ambition. They sent questionnaires to candidates in 1953, asking them where they stood on gay rights. One newspaper called them a "strange new pressure group." That was the moment the mainstream noticed.

Stonewall and the End of an Era

When the Stonewall uprising happened in June 1969, the Mattachine Society of New York didn’t celebrate. They posted signs outside the Stonewall Inn: "We homosexuals plead with our people to please help maintain peaceful and quiet conduct on the streets of the Village." They met with city officials to ask them to stop the protests. That response shocked younger activists. They wanted rage, not restraint. Within weeks, a new group formed: the Mattachine Action Committee. They held a public forum on "Gay Power." Almost 100 people showed up. By July, they voted to organize protests. The old Mattachine was already fading. By 1970, the Gay Liberation Front and other militant groups had taken over. They didn’t want to be respected. They wanted to be heard. And they were loud.Why Mattachine Still Matters

They didn’t win big laws. They didn’t end police raids. They didn’t make homosexuality legal overnight. But they did something deeper. They gave gay people a language to describe themselves. They built the first network of support. They created the first model for organized LGBTQ activism. Without Mattachine, there would have been no blueprint for Stonewall. No legal defense fund. No newsletters. No strategy. No one to say, "We are not alone. We are not broken. We are a community." Historians now call it the first sustained gay rights movement in the U.S. The National Park Service lists it as a foundational force that changed the trajectory of the entire movement. Even today, when you see a Pride parade, you’re seeing the echo of a secret meeting in Los Angeles - where six men dared to imagine a world where they could be free.What Happened After

The New York chapter of the Mattachine Society kept going until 1986. Its archives, preserved by the New York Public Library, show how it slowly shifted from advocacy to survival. By the 1980s, it was focused on AIDS education - a new crisis, but the same mission: protect, inform, organize. The original founders? Harry Hay lived quietly, later becoming a mentor to younger activists. Rudi Gernreich became a famous fashion designer. Dale Jennings faded from public view. But their work didn’t vanish. It became part of the soil from which the modern LGBTQ movement grew.What was the Mattachine Society’s main goal?

The Mattachine Society’s main goal was to challenge the idea that homosexuality was a mental illness or moral failing. They wanted to build a collective identity for gay men, organize politically, and fight discrimination through education and legal defense - not public protests. Their early vision was radical: to treat gay people as a cultural minority with rights, not as criminals or patients.

Why did the Mattachine Society change its leadership in 1953?

The original founders, many of whom had ties to leftist politics, feared government persecution during the McCarthy era. Fearing FBI raids and public exposure, they stepped down. New leaders, more conservative and focused on respectability, took over. They removed radical language, banned Communist members, and shifted the group’s focus from liberation to quiet assimilation - even if it meant accepting laws that criminalized homosexuality.

How did the Mattachine Society fight police harassment?

They fought police harassment by providing legal defense to men arrested in entrapment operations, like Dale Jennings in 1952. They publicized these cases to expose how police targeted gay men in public spaces. They also educated the public and professionals on how entrapment worked. Their success in the Jennings trial - a hung jury - was one of the first legal victories against police abuse in LGBTQ history.

Did the Mattachine Society support the Stonewall riots?

Initially, no. The Mattachine Society of New York urged calm and asked gay people to avoid confrontations after Stonewall. They feared backlash and believed peaceful advocacy was the only way forward. But within weeks, younger members broke away to form the Mattachine Action Committee, which supported protests. This split showed the growing divide between the old homophile movement and the new militant gay liberation movement.

How was the Mattachine Society different from later LGBTQ groups?

Unlike later groups like the Gay Liberation Front, Mattachine avoided public demonstrations, slogans, or direct confrontation. They worked behind the scenes: publishing newsletters, lobbying professionals, offering legal aid. They believed change came through education and respectability, not rage. Later groups rejected that approach, arguing that silence only enabled oppression. Mattachine laid the groundwork - but didn’t lead the revolution.