History of Homosexuality Concept Timeline

First used in a letter to Karl Ulrichs, introducing the concept of a sexual identity rather than just behavior.

Doctors like Krafft-Ebing and Ellis began classifying homosexuality as a medical condition.

"An Inquiry into the Psychology of Sex" describing homosexuality as an "inborn constitutional abnormality."

"Homosexuality" labeled as a "sociopathic personality disturbance" in the first DSM manual.

APA voted to remove homosexuality as a mental disorder after Evelyn Hooker's research and activism.

Academics challenged the binary of gay/straight, introducing terms like "queer" to reject fixed categories.

People use diverse terms like queer, pansexual, nonbinary, and fluid to express identity beyond traditional labels.

The word homosexuality didn’t always exist. Before the 1860s, people didn’t think of same-sex attraction as something that defined who you were. They saw it as something you did-like stealing or lying. A man might have sex with another man, but if he also married a woman, raised kids, and went to church, he wasn’t labeled as anything special. He was just a man who sometimes did something forbidden. That changed in a quiet, almost invisible way, and the shift didn’t come from protest or politics. It came from doctors, lawyers, and scientists trying to classify human behavior like species in a zoo.

The Birth of a Label

In 1868, a Hungarian-German writer named Karl Maria Kertbeny wrote a letter to a German activist named Karl Ulrichs. In it, he used two words for the first time: homosexuality and heterosexuality. He didn’t invent the idea of same-sex love-people had been having it for thousands of years. He invented the idea that it was a type of person. Before this, same-sex behavior was called the "Italian vice," the "English vice," or "oriental mores." It was a crime, a sin, a moral failing. But Kertbeny wanted to remove the moral judgment. He argued that some people were simply born this way. He wasn’t trying to shame them-he was trying to protect them.

Ulrichs, who was openly gay at a time when that could get you locked up, had already been writing about "urnings"-men who were attracted to other men. He borrowed the name from Plato’s Symposium, where Pausanias talks about two kinds of love: one from Uranus (heavenly), and one from Aphrodite (earthly). Ulrichs believed same-sex attraction was natural, not a disease. But he didn’t have the language to make it stick. Kertbeny did. And when the term "homosexual" showed up in medical journals in the 1870s, it spread like wildfire.

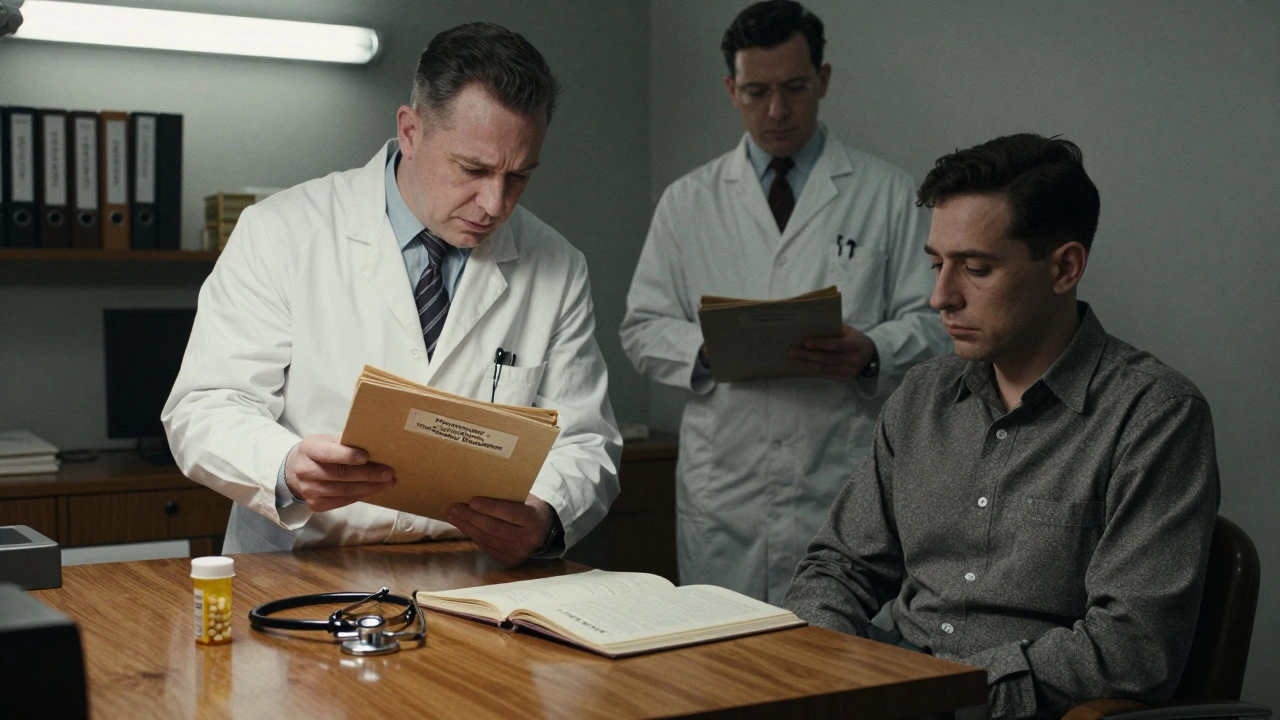

Doctors, Not Priests, Took Charge

By the 1880s, doctors like Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis were writing books that treated homosexuality as a medical condition. Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis listed homosexuality among "perversions," but he also wrote that some people were born with it. Ellis, in his 1896 book, called it an "inborn constitutional abnormality." Both men were conflicted. They saw it as natural, yet still "abnormal." That contradiction became the foundation of modern gay identity: you were not evil, but you were not normal either.

This was a huge shift. Before, the church decided what was sinful. Now, the hospital decided what was sick. And being labeled "sick" had consequences. People were institutionalized. Forced into treatments. Some were castrated. But it also gave people a new kind of community. If you were one of these "homosexuals," you weren’t alone. You belonged to a group. A category. A tribe.

The Long Road Out of the DSM

In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association put "homosexuality" in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). It was listed as a "sociopathic personality disturbance." That meant therapists were trained to "cure" it. In 1956, a psychologist named Evelyn Hooker did something radical. She tested 30 gay men and 30 straight men on psychological tests. She showed the results to experts who didn’t know who was who. They couldn’t tell the difference. The gay men weren’t more disturbed. Some were more stable. Hooker’s research was ignored for years. But it was the first hard evidence that homosexuality wasn’t a mental illness.

Activists picked up the study. By the early 1970s, gay rights groups were staging protests at APA meetings. They held signs that said "Psychiatry Is the Enemy." In 1973, after years of pressure, the APA voted to remove homosexuality from the DSM. It wasn’t because science suddenly changed. It was because people refused to accept the label. The removal didn’t end discrimination. But it did end the official medical excuse to treat gay people as broken.

Identity vs. Construction

Just when it seemed like "homosexuality" was finally accepted as normal, scholars started asking a deeper question: Is it even real? In the 1970s, thinkers like Michel Foucault and Mary McIntosh argued that "homosexuality" as we know it didn’t exist before the 19th century. It wasn’t discovered-it was invented. Before then, people didn’t think of themselves as "gay" or "straight." They thought of themselves as people who did certain things. The idea that your entire identity-your soul, your worth, your future-was tied to who you slept with was a modern invention.

Foucault called it a "species." The sodomite was a temporary sinner. The homosexual was a permanent type. And once you became that type, you had to live inside the box they made for you. You joined clubs. You read books. You fought for rights. You got married. You came out. All of it was shaped by a category that didn’t exist a hundred years ago.

Anthropologists found cultures where same-sex relationships were common but didn’t come with identity labels. In Native American communities, "Two-Spirit" people existed long before Europeans arrived. They weren’t called "gay" or "lesbian." They had their own roles, their own names, their own spiritual meaning. The idea that everyone must fit into one of two boxes-gay or straight-is a Western idea. It’s not universal.

The Paradox of the Label

Here’s the twist: the label that once made you a criminal became the tool that gave you rights. Without "homosexuality" as a category, there would be no gay rights movement. No Pride parades. No marriage equality. No legal protections. But at the same time, the label locked people in. If you didn’t fit neatly into "gay" or "straight," you were invisible. Bisexual people were dismissed as confused. Transgender people were folded into the wrong category. Queer people were told to pick a side.

That’s why, in the 1990s, queer theory exploded. Scholars like John D’Emilio and Jonathan Ned Katz argued that "homosexuality" was just one way of organizing desire-and not the only one. Queer wasn’t just a slur. It was a rejection of boxes. It was a way to say: I don’t fit your categories, and I never will.

What Comes Next?

Today, the word "homosexuality" is still used in laws, medical records, and surveys. But younger generations are moving beyond it. They use "queer," "pansexual," "nonbinary," "fluid." They don’t want to be labeled by their partners. They want to be defined by their own terms. Digital spaces let people create identities that didn’t exist before. A 16-year-old in Kansas can find a community of nonbinary people in Manila through TikTok. That kind of connection wasn’t possible in 1960.

Still, the legacy of "homosexuality" lingers. It gave us visibility. It gave us language. It gave us the right to say, "I am not sick." But it also made us think that our worth was tied to how we fit into someone else’s system. The real revolution isn’t just about being accepted. It’s about refusing to be defined by a category that was never meant to hold us.

When was the term "homosexuality" first used?

The term "homosexuality" was first used in a letter written by Karl Maria Kertbeny on May 6, 1868. He later published it in a pamphlet in 1869 as part of an effort to decriminalize same-sex relationships by framing them as a natural variation, not a moral crime.

Was homosexuality always considered a mental illness?

No. Before the 19th century, same-sex behavior was seen as a sin or crime. It became classified as a mental illness only after doctors and psychologists began studying sexuality as a medical field in the 1870s. The American Psychiatric Association listed it as a disorder in the DSM until 1973, when it was removed after years of activism and scientific evidence.

How did Karl Ulrichs contribute to the idea of homosexuality?

Karl Ulrichs was one of the first people to argue that same-sex attraction was innate, not chosen. In the 1860s, he published pamphlets introducing the term "urning" to describe men attracted to men. He based his ideas on ancient Greek philosophy and claimed urnings were a natural third sex. His work laid the foundation for modern LGBTQ+ rights activism.

Why did Michel Foucault say "the homosexual was now a species"?

Foucault meant that before the 19th century, same-sex acts were seen as occasional behaviors anyone might commit. Afterward, people began to believe that some individuals were fundamentally different-"homosexuals" as a distinct type of person. This shift turned behavior into identity, and identity into a category that could be studied, controlled, and pathologized.

Are all cultures the same in how they view same-sex relationships?

No. Many cultures have had same-sex relationships without using the concept of "homosexuality." For example, Native American "Two-Spirit" people, the Bugis of Indonesia with their five genders, and the "muxe" in Mexico all have distinct roles and identities that don’t map onto Western gay/straight categories. The idea that everyone must fit into two boxes is a modern Western invention.

Is the term "homosexuality" still useful today?

It’s still used in legal and medical contexts for clarity, but many people find it limiting. It forces people into a binary and ignores the diversity of gender and attraction. Terms like "queer," "pansexual," or "nonbinary" are more inclusive and reflect how people actually experience identity today. The term has historical value, but it’s not the full story.