Historical Medical Vibrator Price Converter

Equivalent historical value:

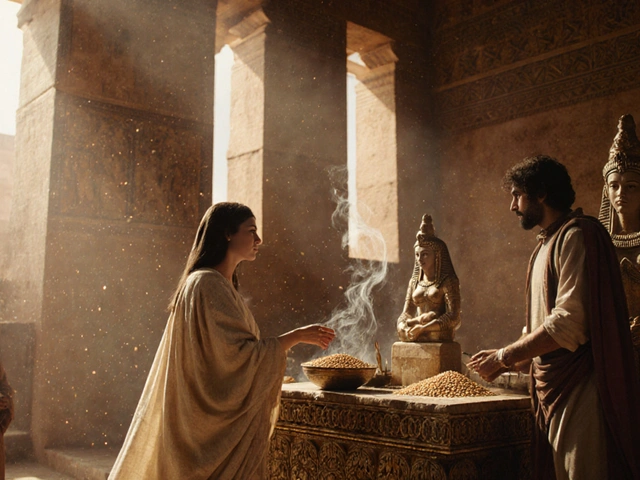

Before electricity, before the word "sex toy" even existed, there were machines designed to shake women’s bodies - not for pleasure, but for medicine. In the 1700s, a French inventor created a spring-driven device called the tremoussoir, a hand-wound mechanical vibrator that could produce 30 to 50 vibrations per minute. It wasn’t sold in back-alley shops or hidden under mattresses. It was advertised in medical catalogs, sold to doctors, and used in clinics as a treatment for a condition called female hysteria.

What Was Female Hysteria, Really?

Female hysteria wasn’t just a made-up term. It was a real diagnosis in medical textbooks from the 18th century until 1952. Doctors described it as a nervous disorder caused by a "wandering uterus," with symptoms ranging from anxiety and irritability to fainting and sexual longing. The cure? Pelvic massage - manual, repetitive, and exhausting. One physician might spend hours a day massaging patients. By the 1860s, doctors were looking for a better way.Enter the mechanical vibrator. The idea wasn’t to give women orgasms - that was never said out loud. It was to relieve "hysterical paroxysm," a medical term for orgasm, which doctors had observed was the natural end of the massage. The device was just a tool to speed up the process. As historian Rachel P. Maines wrote, vibrators were invented to save doctors’ hands, not to liberate women’s sexuality.

The Steam-Powered Machine That Took Up a Room

In 1869, Dr. George Taylor of New York built something far more ambitious than the tremoussoir: the Manipulator. It wasn’t battery-powered or hand-cranked. It was steam-powered. A full boiler sat in a separate room, producing 15 to 20 pounds of steam pressure. A rod connected through the wall to a padded handle that the patient lay against. The machine shook for 15 to 20 minutes per session. It weighed over 150 pounds. It cost more than most families made in a month. It was never meant for home use.

And yet, it worked. Patients reported relief. Doctors praised its efficiency. Taylor’s device was essentially an inefficient steam engine with an attached dildo - deliberately sloppy in design to maximize vibration. As Maines put it, "It was engineered to be bad at being an engine, so it could be good at being a vibrator."

The Hand-Cranked Alternative That Still Took Effort

Not everyone could afford a steam engine in their office. So in the 1880s, Gerald Macaura - who claimed to be a doctor but wasn’t - sold a hand-cranked device called the Pulsocon. It could hit up to 5,000 vibrations per minute, but you had to turn the crank the whole time. It weighed three pounds and was about 12 inches long. It was portable, but it wasn’t easy. A single session could leave a physician’s arm aching. Still, it was cheaper than steam, and it worked fast.

Doctors didn’t advertise it as a sexual device. They called it a "blood circulator." It was sold to treat neuralgia, rheumatism, and "general debility." No mention of orgasms. No mention of pleasure. Just "therapeutic stimulation."

How They Were Sold: The Art of Medical Camouflage

Marketing these devices took skill. You couldn’t say "this will make your wife climax." So they didn’t. Instead, they used medical language that sounded legitimate and safe.

The Chattanooga Manufacturing Company’s 1900 catalog called their device the Vitalizer. It promised "1,000 gentle vibrations per minute" and "no tiresome hand movement required." It was for "sore muscles" and "nervous exhaustion." Sears Roebuck sold them in their 1907 catalog as "personal massagers" - for headaches, insomnia, and fatigue. Montgomery Ward called them "indispensable for the modern home."

These weren’t sex toys. They were medical appliances. And they were sold alongside electric belts, hydrotherapy machines, and spinal adjusters. The packaging was clean, the language was clinical, and the buyers were often women who thought they were buying relief from stress - not sexual release.

What Did Women Actually Think?

Women didn’t always know what these devices were really for. A 1992 survey by the Kinsey Institute found that 28% of women born before 1920 had used a vibrator - but most didn’t realize it could lead to orgasm. One woman, Mary Jane Cowley, wrote in her 1905 diary: "The device has provided remarkable relief from my headaches, though I confess it produces rather surprising secondary effects."

Doctors knew. They wrote about it in private notes. But they never told their patients outright. The social stigma around female sexuality was too strong. So they gave women a tool that delivered pleasure under the cover of medicine. As scholar Hallie Lieberman noted, "This allowed women to access sexual pleasure while maintaining social respectability."

Electricity Changed Everything - But Not the Marketing

The first electric vibrator appeared in 1883, but it didn’t become common until the 1890s. By 1902, Chattanooga’s electric Vitalizer was selling 17,000 units a year. It cost $15 - about $500 today. It didn’t need a boiler or a crank. You plugged it in, turned it on, and let it do the work.

But the marketing didn’t change. Sears still sold them as "personal massagers." Doctors still prescribed them for "nervous conditions." Even in the 1930s, when religious groups complained, Sears pulled them from the catalog - only to bring them back in 1946 with the same language. "For muscular tension," they said. "For relaxation."

It wasn’t until the 1960s, when sex researchers like William Masters and Virginia Johnson began studying human arousal, that the truth started to leak out. Betty Dodson, a feminist activist, began teaching women in the late 1960s that orgasm wasn’t a medical side effect - it was a right. She told them to use the vibrator they already owned, not as a cure, but as a tool for pleasure.

The Legacy: A Medical Tool That Became a Symbol of Liberation

For nearly 240 years - from 1734 to 1973 - vibrators were legal to sell in the U.S. with no restrictions. Not because society approved of them, but because no one wanted to admit what they were really for. The devices were always there, quietly changing lives, hidden in plain sight under the label of "therapy."

Today, we think of vibrators as symbols of sexual freedom. But their origins are far more complicated. They were born from medical arrogance, shaped by gender norms, and disguised in clinical jargon. The same machines that were once used to "cure" women of their desires now help them reclaim them.

The tremoussoir didn’t invent pleasure. But it did make it possible - without saying a word about it.