Sexual vs Asexual Reproduction Simulator

Simulation Parameters

Results

For over a billion years, life reproduced the same way: by making copies. One cell split in two. A bacterium divided. A fungus sent out spores. Offspring were clones-exact genetic duplicates of the parent. Simple. Efficient. No need to find a mate. No wasted energy on courtship or competition. Then, something changed. Something so radical it rewrote the rules of life itself. Sexual reproduction emerged. Not just as a tweak, but as a full-scale overhaul of how genes are passed down. And somehow, despite being slower, costlier, and more complicated, it took over the planet.

The Cost of Being Sexual

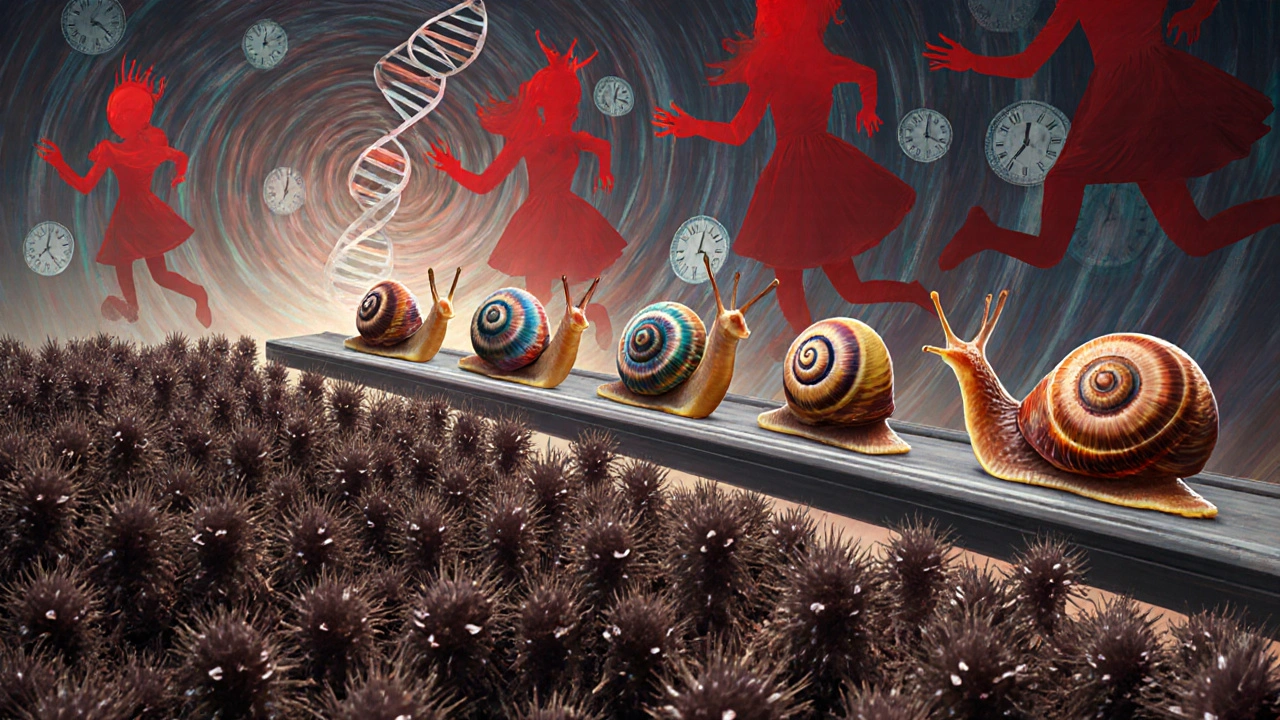

Imagine two populations of the same species. One reproduces asexually. Every individual makes identical copies of itself. The other reproduces sexually. Each parent passes only half their genes to each offspring. At first glance, the asexual group should dominate. They produce twice as many offspring. Every individual is a reproducer. In the sexual group, only half the population-females-can bear young. Males don’t produce offspring directly. This is the twofold cost of sex, first described by evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith in 1978. It’s a math problem that still stumps scientists: if asexual reproduction is so efficient, why isn’t everything asexual? The answer isn’t obvious. In stable environments, asexual species thrive. Bdelloid rotifers, tiny freshwater animals, have survived without sex for at least 40 million years. They’ve cloned themselves through droughts, ice ages, and mass extinctions. Yet, across the tree of life, over 99% of animal species use sex. Plants, fungi, protists-they all rely on it. Why? Because sex doesn’t just copy genes. It remixes them.The Power of Mixing Genes

Asexual reproduction is like photocopying a document. Every error stays. Every advantage stays. Sexual reproduction is like taking two different versions of the same document, cutting out paragraphs, and gluing them together into something new. That’s genetic recombination. It happens during meiosis, when sperm and egg cells form. Chromosomes swap pieces. Genes shuffle. The result? Each offspring is genetically unique. This isn’t just about variety. It’s about survival. In a world full of parasites, pathogens, and changing conditions, being identical is dangerous. If a virus evolves to infect one clone, it can wipe out the whole group. But if every individual has a different genetic mix, some will survive. That’s the core idea behind the Red Queen hypothesis, named after the character in Alice in Wonderland who says, “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” Evidence? Look at New Zealand freshwater snails. Scientists compared sexual and asexual populations in the same lakes. The asexual snails had 63% more parasites. The sexual ones kept ahead. Their genes were constantly shifting, making it harder for parasites to adapt. In lab experiments with fruit flies, sexual populations accumulated beneficial mutations 37.8% faster than asexual ones. Natural selection worked better because it had more variation to act on.How Did It Start?

The transition from cloning to gametes didn’t happen overnight. It didn’t require a single mutation. It needed a chain of changes-many of them invisible at first. Scientists now believe the tools for sex were already there, repurposed from older systems. DNA repair mechanisms in ancient bacteria could have been the starting point. When cells needed to fix broken DNA, they sometimes borrowed pieces from nearby cells. That’s not sex. But it’s close. Around 1 to 2 billion years ago, single-celled eukaryotes began experimenting. Some started exchanging genetic material temporarily. Then, they started keeping it. The diploid stage-having two copies of each chromosome-became useful. It masked bad mutations. If one copy was broken, the other could compensate. That’s called complementation. It gave hybrids an edge. Over time, this led to the evolution of gametes: specialized cells that carried half the genome. Sperm and egg weren’t invented-they evolved from simpler reproductive cells. Fungi offer a glimpse into this transition. Researchers have found 17 intermediate reproductive strategies in fungi today-some reproduce mostly asexually, but can switch to sex under stress. These aren’t fossils. They’re living examples of how sex can evolve incrementally. Dr. Sarah Otto’s team at the University of British Columbia showed that facultative sex-sex when needed-can evolve naturally. No grand leap required.

The Molecular Toolkit

We now know that sex isn’t just about behavior. It’s built into our genes. A landmark 2023 study in Cell identified 17 core genes involved in meiosis-the process that creates gametes. These genes are found in nearly all sexually reproducing species, from algae to humans. Even more telling: they’re nearly identical to genes used in DNA repair in bacteria. Evolution didn’t invent a new system. It tweaked an old one. The same genes that fix breaks in DNA also help chromosomes pair up, swap segments, and split cleanly during meiosis. This is why sex is so widespread. It didn’t require a miracle. It required a repurposing. Once the machinery was in place, natural selection favored those who used it. The benefits-faster adaptation, better mutation cleanup-outweighed the costs.Why It Still Matters Today

This isn’t just ancient history. It’s happening now-in labs, in farms, in hospitals. Hybrid corn, which relies on controlled sexual reproduction, generates $8.2 billion annually in the U.S. alone. Crop breeders use sex to combine disease resistance with high yield. Without it, we’d be stuck with low-yield, fragile varieties. In medicine, cancer is often a failure of sex. Tumors grow by cloning themselves. They bypass meiosis. They ignore recombination. That’s why they accumulate mutations so fast-and why they become resistant to treatment. The Cancer Genome Atlas found that 78% of solid tumors show signs of lost sexual reproduction mechanisms. Understanding how sex keeps genomes clean helps us fight cancer. Even synthetic biology is borrowing from evolution. Researchers are designing genetic circuits inspired by meiosis-systems that can shuffle and test gene combinations automatically. One team at MIT used CRISPR to trigger facultative sex in yeast, mimicking how ancient organisms might have transitioned. It worked.

Still Unanswered

We know a lot. But we don’t know everything. How did internal fertilization evolve? How did mating organs form? Why did some species, like certain lizards and sharks, evolve parthenogenesis-sex without males-after millions of years of sex? These are open questions. Some argue that sex is too complex to evolve naturally. But biology doesn’t need perfection. It just needs advantage. A small benefit, repeated over millions of generations, becomes a revolution. The fact that sex exists at all-despite its cost-is proof that it works. Better than cloning. Better than copying. Better than staying the same.What We Know for Sure

- Asexual reproduction is efficient but fragile. Sexual reproduction is costly but flexible.- Genetic recombination through meiosis is the engine behind evolutionary innovation.

- The Red Queen hypothesis best explains why sex dominates in changing, parasite-rich environments.

- The molecular tools for sex were repurposed from ancient DNA repair systems.

- Sexual reproduction increases speciation rates by 58% over geological time.

- Over 99% of animal species use sex because it outlasts cloning in the long run.

- Cancer and crop failure both show what happens when sex breaks down.

Life didn’t choose sex because it was easy. It chose sex because it was powerful. And that’s why, after two billion years, we’re still here-different, diverse, and never quite the same as our parents.

Why is sexual reproduction more common than asexual reproduction if it’s less efficient?

Sexual reproduction is less efficient because it requires two parents and only passes on 50% of each parent’s genes. But it creates genetic diversity through recombination. This diversity helps populations adapt faster to diseases, environmental changes, and parasites. Over time, this advantage outweighs the cost. While asexual species thrive in stable environments, sexual species dominate in changing ones-and most environments change.

What is the Red Queen hypothesis?

The Red Queen hypothesis says that sexual reproduction evolved as a defense against rapidly evolving parasites. Just like the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland who says you must run just to stay in place, hosts must constantly shuffle their genes to stay ahead of pathogens. Studies on snails and fruit flies show sexual populations have fewer parasites and adapt faster than clones. It’s not about being faster-it’s about being harder to predict.

Did sex evolve from asexual reproduction, or did both evolve together?

Sex evolved from asexual ancestors. All sexually reproducing organisms share a common single-celled eukaryotic ancestor that lived 1-2 billion years ago. That ancestor was likely asexual. The machinery for sex-meiosis, gamete formation, genetic recombination-evolved gradually from older systems like DNA repair. We see this in modern organisms like fungi and algae that can switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on conditions.

Can organisms switch between sexual and asexual reproduction?

Yes. Many organisms, including aphids, certain lizards, and fungi, can switch. They reproduce asexually when conditions are stable and safe, then switch to sex when stress hits-like drought, disease, or overcrowding. This flexibility suggests sex isn’t a fixed trait but a tool. Evolution favors organisms that can use the right strategy at the right time.

How do scientists study the evolution of sex?

Researchers use model organisms like fruit flies, nematodes, and yeast. They create controlled populations, track mutations over hundreds of generations, and compare sexual and asexual lines. Genomic sequencing now lets them see exactly which genes change. Long-term experiments, like Richard Lenski’s E. coli study running for over 75,000 generations, show how traits evolve. Lab experiments with CRISPR are even letting scientists trigger sexual behavior in normally asexual species.

Why do some species, like bdelloid rotifers, survive without sex for millions of years?

Bdelloid rotifers survive without sex because they live in isolated, stable environments like temporary ponds. They’ve evolved other ways to deal with mutations-like absorbing DNA from their surroundings and repairing their own genomes aggressively. But they’re the exception. Most lineages that abandon sex eventually go extinct. Their long-term survival is rare and still being studied.

Is there a link between sexual reproduction and cancer?

Yes. Cancer cells often behave like asexual clones-they multiply without recombination, ignoring the checks and balances of meiosis. This lets them accumulate mutations rapidly, leading to drug resistance and spread. Studies show 78% of solid tumors show signs of broken sexual reproduction mechanisms. Understanding how sex keeps genomes stable helps scientists design better cancer treatments that target mutation-prone cells.