Ancient Consent Laws Quiz

Test Your Understanding

Answer these questions about the Hittite and Assyrian laws on sexual consent. Select the correct answer and check your results!

Results

When you think of the oldest laws about sexual consent, you probably don’t picture clay tablets from 3,500 years ago. But in the ancient Near East, long before Greece or Rome, two powerful civilizations - the Hittites and the Assyrians - wrote down rules about what counted as consent, and what didn’t. These weren’t abstract ideas. They were practical, enforceable laws, carved into stone and clay, meant to keep order in bustling cities and rural villages alike. And what they reveal is startling: one society had a surprisingly modern clause recognizing mutual willingness as legal protection, while the other responded to rape with a brutal, tit-for-tat punishment that targeted the perpetrator’s wife.

The Hittite Code: Consent as a Legal Shield

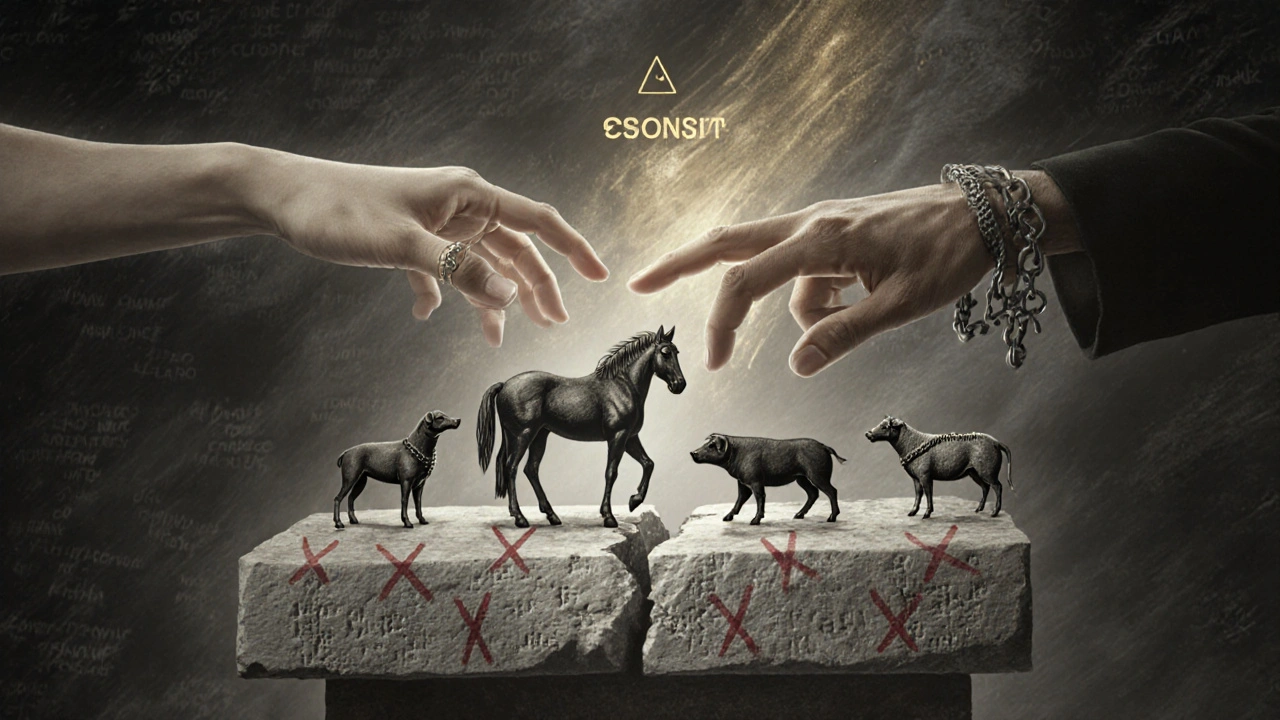

The Hittite Code, written between 1650 and 1500 BCE in what is now central Turkey, stands out for one reason: it explicitly said that if a man and a woman had sex willingly, there was no crime. That’s not a modern idea - it’s from a legal text older than the Bible. Clause §190 of the Hittite Laws reads: “If a man and a woman came together sexually willingly, and [had] intercourse, there shall be no punishment.” This isn’t just a footnote. It’s one of the earliest known legal declarations that consent matters - and that mutual agreement removes criminal liability. This wasn’t just theoretical. The Hittites had a system where local assemblies, called panku, handled cases. Judges were appointed by the king, and witnesses were required to prove what happened. If someone claimed rape, they had to back it up. That’s a procedural safeguard most ancient societies didn’t bother with. And yet, the Hittites didn’t apply this protection equally. It only clearly covered free citizens. Slaves, foreigners, and women without male guardians were left out. Historian Tikva Frymer-Kensky pointed out that the law’s generosity was limited by class and gender. A noblewoman’s consent mattered; a slave woman’s didn’t. The Hittites also had clear rules about what was off-limits. Bestiality was punishable by death - but only for cows, sheep, pigs, and dogs. Horses and mules? Exempt. Scholars still argue why. Some say it was religious: horses were sacred, tied to the gods. Others, like Gary Beckman, think it was practical. Horses were valuable, used for transport and war. Punishing their use as sexual objects might have disrupted the economy. Either way, the exception tells us the law wasn’t just about morality - it was about control, resources, and social function.The Assyrian Response: Punishment Through Retribution

The Middle Assyrian Laws, written around 1400-1100 BCE in northern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), took a different path. They didn’t focus on consent as a legal defense. Instead, they focused on damage control - specifically, damage to family honor and male authority. When a man raped an unbetrothed virgin, the law didn’t punish him by imprisoning him or fining him. It forced him to marry her. And then came the twist: the rapist’s wife had to be raped by the girl’s father or brothers. That’s not a metaphor. That’s Law §55 of the Middle Assyrian Laws. This wasn’t about protecting the victim. It was about restoring balance in a society where women were seen as property - daughters, wives, sisters - belonging to men. The rape wasn’t just a crime against the woman; it was a theft from her father or future husband. The punishment wasn’t meant to stop violence. It was meant to make the rapist suffer the same loss of control over his own household. David P. Wright calls it a “brutal but sophisticated” recognition of trauma - but it’s trauma inflicted on another woman, not the victim. The victim’s voice? Still silent. Assyrian law was rigidly hierarchical. If a slave raped a free woman, the punishment was death. But if a free man raped a slave woman, the penalty was often just a fine - paid to her owner. Consent didn’t matter if the victim wasn’t someone’s property. The law didn’t care whether she resisted. It cared whether her owner lost control.

Homosexuality: Two Very Different Approaches

The Hittites didn’t outlaw consensual same-sex relations. In fact, their laws only punished non-consensual acts. Clause §189 says: “If a man violates his daughter, it is a capital crime. If a man violates his son, it is a capital crime.” Notice what’s missing: no mention of consensual sex between men. There’s no law saying “a man shall not lie with a man.” That’s not an oversight - it’s a deliberate silence. Gordon J. Wenham and Harry Hoffner both noted that Hittite law didn’t criminalize homosexuality. It criminalized abuse of power - especially when it involved family members. The Assyrians were the opposite. Their laws explicitly targeted male homosexuality. Law §17 and §18 say that if a man had sex with another man, he would be castrated. This wasn’t about consent. It was about gender roles. In Assyrian society, being the passive partner in a male-male act was seen as a violation of masculinity - a loss of status. The punishment wasn’t about the act itself. It was about enforcing hierarchy. A man who allowed himself to be penetrated was no longer seen as a full man - and the law made sure everyone knew it.

The Gaps: Who Was Left Out?

Both legal systems had glaring blind spots. Neither protected men from sexual violence unless the victim was a son and the perpetrator was his father. That’s it. There’s no law saying, “If a man is raped by another man, he gets justice.” Male victims outside the father-son relationship? Invisible. Marten Stol, a leading scholar of ancient sexuality, called this a “systemic silence.” In a world where men were supposed to be strong, dominant, and in control, being violated was unthinkable - and therefore, unaddressed. Women’s consent was only recognized when it affected a man’s property. A married woman’s adultery? Death penalty under both Hittite and Assyrian law. But if she was raped by someone other than her husband, the punishment depended on who she belonged to - her father, her husband, or her master. Her feelings? Irrelevant. The law didn’t ask if she said no. It asked: Did she resist? And if she didn’t? That was interpreted as consent. That’s not protection. That’s blame. Slaves had no legal standing in sexual matters. In Assyrian law, a slave woman’s body was her owner’s to use. In Hittite law, slaves could marry, buy property, even buy their freedom - but only if their owner allowed it. Consent was a privilege, not a right.Legacy: What These Laws Tell Us

These ancient codes weren’t just about sex. They were about power. Who had it? Who didn’t? Who got to decide what was right? The Hittites showed that consent could be a legal concept - even if it was limited. The Assyrians showed how deeply gender, class, and ownership were woven into the idea of justice. What’s remarkable is how much we’ve learned from these tablets. Before archaeologists dug up Hattusa and Assur in the early 1900s, we thought ancient law was all about harsh punishments - eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth. But the Hittite consent clause and the Assyrian reciprocal rape provision show something deeper: these societies were trying to make sense of human behavior. They were wrestling with the same questions we still ask today: What does consent mean? Who gets to define it? Who gets protected? Modern legal systems still struggle with these questions. But the Hittites and Assyrians were the first to write them down. They didn’t get it right. But they tried. And that matters.Did the Hittites have a law that recognized sexual consent?

Yes. Clause §190 of the Hittite Code explicitly states that if a man and a woman had sex willingly, there was no punishment. This is one of the earliest known legal recognitions of mutual consent in human history, dating to around 1650-1500 BCE. However, this protection applied only to free citizens and did not extend to slaves or foreigners.

How did Assyrian law handle rape?

The Middle Assyrian Laws (MAL A §55) handled rape by forcing the perpetrator to marry the victim and then requiring the victim’s father or brothers to rape the rapist’s wife. This wasn’t about protecting the victim - it was about restoring family honor and punishing the rapist through symbolic retribution. The victim’s trauma was acknowledged, but her agency was ignored.

Were homosexual acts illegal in Hittite and Assyrian law?

No - not in Hittite law. The Hittites only punished non-consensual same-sex acts, such as a father violating his son. Consensual male-male relations were not outlawed. In contrast, Assyrian law (MAL A §17-18) explicitly criminalized male homosexuality, prescribing castration as punishment, particularly for the passive partner, reflecting strict gender roles.

Why were horses and mules exempt from Hittite bestiality laws?

The exemption of horses and mules from the death penalty for bestiality in Hittite Law (§187-188, §199-200) remains debated. Some scholars, like Itamar Singer, suggest it was because these animals had sacred or ritual significance. Others, like Gary Beckman, argue it was practical: horses were vital for warfare and transport, and criminalizing their use would have disrupted the economy. The law reflects real-world priorities, not just moral codes.

Did these laws protect women equally?

No. Both legal systems treated women as property - daughters, wives, or slaves - belonging to men. A woman’s consent mattered only if it affected a man’s rights. A noblewoman’s rape carried a heavier penalty than a slave woman’s, not because of her suffering, but because of the loss to her male guardian. Resistance was expected; failure to resist was often interpreted as consent, placing the burden on the victim.

How do these ancient laws compare to modern views on consent?

The Hittite consent clause is strikingly similar to modern principles - mutual agreement removes criminal liability. But unlike today, their consent was conditional on social status. Modern law aims for universal consent regardless of class, gender, or status. Assyrian law, with its focus on retribution and honor, is closer to ancient vengeance systems than modern justice. Neither system fully recognized individual autonomy - a gap we’re still working to close.