Roman Sexual Roles Quiz

What was the most important factor determining social status in Roman sexual encounters?

Why was the woman-on-top position considered shameful for Roman men?

What was the significance of oral sex for Roman men?

What was the purpose of the lost text 'Tablets of Philaenis'?

How did Roman society view the sexual role of women?

When you think of ancient Rome, you probably picture emperors, gladiators, and marble temples. But beneath the surface of that grand civilization was a complex, often surprising, approach to sex-one that had little to do with modern ideas of romance or equality, and everything to do with power, status, and control.

The Rules Were Clear: Active vs. Passive

Roman sexuality wasn’t about who you loved. It was about who you dominated. The central rule was simple: a free Roman man had the right to penetrate, but never to be penetrated. This wasn’t about orientation-it was about social hierarchy. A man could have sex with women, boys, slaves, or foreigners, as long as he stayed in the active role. If he took the passive role, he risked losing his reputation, his political standing, even his citizenship.This wasn’t just a social norm-it was enforced in law and ridicule. When Julius Caesar was young, rumors spread that he had been the passive partner to King Nicomedes of Bithynia. His enemies called him “Queen of Bithynia.” That wasn’t just gossip; it was political warfare. Being called a “wife” by a man was one of the worst insults you could receive.

What Positions Did They Actually Use?

Roman texts and art give us a surprisingly detailed picture of sexual positions. The most common was the woman lying on her back, legs apart-what they called the “natural manner.” Ovid, in his Ars Amatoria, advised men to adjust positions based on a woman’s body shape. “She who is noteworthy in face,” he wrote, “let her be supine.” It wasn’t about pleasure for her-it was about control, comfort, and aesthetics.Other positions were documented too: sitting, side-lying, standing, and the woman-on-all-fours position, which Romans called the “doggy style.” Unlike today, where this position is often seen as purely physical, Romans viewed it as natural and even fertile. Animals were respected in Roman culture, and this posture mirrored how dogs and horses mated. It was acceptable-even preferred-for married couples.

But the woman-on-top position? That was taboo. Romans called it “riding like a horse,” and it implied the man was being controlled. In Pompeii, prostitutes who performed this position charged double. It wasn’t because it was more pleasurable-it was because it broke the social code. A man letting a woman take charge was seen as weak, unmanly, and dangerously close to the status of a slave.

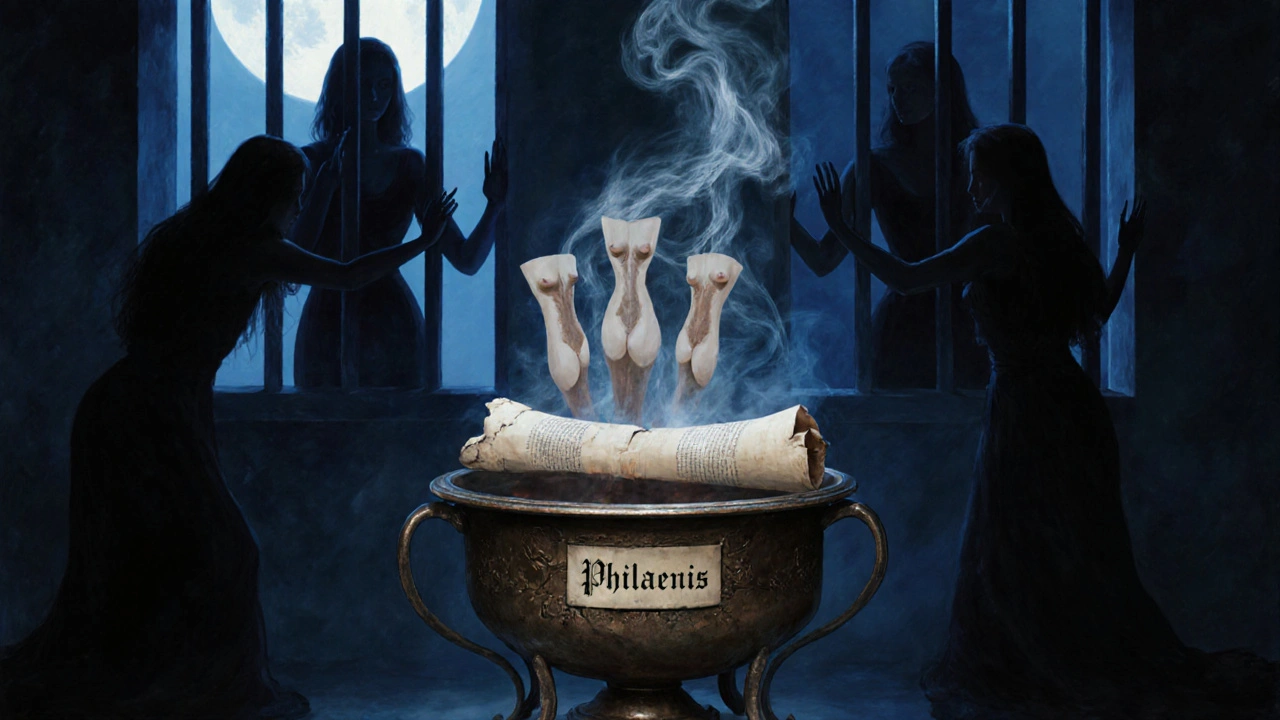

The Lost Manual: Philaenis and the Seven Postures

There was once a book called the Tablets of Philaenis, attributed to a woman who supposedly wrote a detailed guide to sexual positions. It’s lost now, but Roman writers like Lucian and Martial referenced it as the ultimate source of filthy knowledge. Scholars like Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, in their 1890 translations, noted that Philaenis’s text listed seven distinct postures of coition. These weren’t just random suggestions-they were a catalog of techniques, some practical, some extreme.Why did this book disappear? Because it threatened the hierarchy. If women had written manuals on sex, it meant they had knowledge, agency, and authority. That was dangerous in a society built on male dominance. The very mention of Philaenis became shorthand for moral decay. By the 2nd century CE, saying “Philaenis-style” was enough to shock an audience.

Oral Sex: A Double Standard

Romans didn’t see oral sex as immoral in itself-it was about who was doing what. A man receiving oral sex from a woman or boy? Fine. A man performing cunnilingus? That was disgraceful. Martial, the poet, mocked men who did it, calling them “depraved.” Why? Because it meant he was lowering himself to serve a woman. In Roman eyes, pleasure wasn’t shared-it was taken or given as a sign of power.But here’s the twist: women weren’t expected to enjoy sex. The clitoris, which Romans called the landica, was known to medical writers. Some doctors even performed procedures to “trim” it if it was too large, believing it caused “hysteria.” This wasn’t religious-it was medical. But it still reveals the truth: female pleasure was seen as a problem to be managed, not a right to be honored.

What the Art Tells Us

The paintings in Pompeii’s Suburban Baths, discovered in 1986 and published in 1995, show scenes that would shock even modern viewers: group sex, male-male acts, female-female acts, and oral sex. These weren’t hidden away-they were painted on the walls of a public bathhouse. So why the contradiction between the art and the texts?The answer is context. The baths were places of leisure, not morality. These images were meant to amuse, not instruct. They were satire, fantasy, or even jokes. They didn’t reflect how most Romans lived-they reflected what Romans found funny or shocking. The same way a modern meme might show absurd sex acts, these paintings were meant to make you laugh, not copy.

Women, Slaves, and the Silence of the Record

Here’s the hardest truth: Roman sexual texts were written by men, for men. Women’s voices are nearly absent. When Suetonius wrote that Emperor Claudius “had a curiosity for women,” he wasn’t praising him-he was mocking him for being too ordinary. Female same-sex relationships? We have no clear descriptions. Only vague guesses from male writers who didn’t care enough to record them. “It simply didn’t matter,” as one modern analysis puts it, “because women didn’t matter.”Slaves and foreigners had no legal rights, so their sexual experiences were never recorded unless they were used as punchlines. A slave boy’s pleasure? Irrelevant. A female slave’s consent? Not a question.

Modern Misunderstandings

We often project modern ideas onto the past. We assume Romans were “liberated” because they had more sexual freedom. But their freedom was only for a few. For women, slaves, and non-citizens, sex was rarely a choice-it was a duty, a risk, or a punishment.And we misread their art. Those Pompeian frescoes aren’t proof of a sexually open society. They’re proof of a society obsessed with control, hierarchy, and performance. The man on top? Power. The woman on top? Shame. The man being penetrated? Ruin.

What makes Roman sexuality so fascinating isn’t how different it was from ours-it’s how similar. We still tie sex to power. We still punish men for being “too passive.” We still shame women for taking control. The Romans just made it more explicit.

Why This Matters Today

Studying Roman sexual practices isn’t about titillation. It’s about seeing how deeply culture shapes intimacy. Power, not love, dictated who touched whom, how, and why. The same patterns echo today-in workplaces, in relationships, in politics. When we call someone “a bottom” as an insult, we’re using a Roman idea.The Romans didn’t have a word for “homosexuality” because they didn’t think in terms of identity. They thought in terms of roles. And that’s the real lesson: sex isn’t just about bodies. It’s about who holds the power-and who’s forced to submit.

Were Roman sexual positions documented in medical texts?

Yes. Medical writers like Galen and Lucretius discussed sexual practices in clinical terms, focusing on fertility, anatomy, and health. They recognized the clitoris (called landica) and even described procedures to alter it for medical reasons, such as treating hysteria. These weren’t moral judgments-they were physiological observations, though still framed within a patriarchal worldview.

Did Roman women have any sexual agency?

Very little. While elite women could own property and manage households, their sexual behavior was tightly controlled. Adultery was punished severely, especially if it involved a citizen man. Female pleasure was rarely acknowledged. Any sexual activity outside marriage or procreation was seen as dangerous. The few exceptions-like the women in Pompeii’s brothels-were treated as commodities, not partners.

Why was the woman-on-top position considered shameful?

Because it reversed the natural order of dominance. In Roman thought, the man was supposed to be the active, controlling force. If a woman rode him, it implied he was passive-like a horse being ridden. This was humiliating for a free Roman man. In brothels, it was priced higher because it was seen as an extreme, transgressive act-not because it was more pleasurable, but because it broke social rules.

What role did slavery play in Roman sexual practices?

Slavery was central. Roman men could legally have sex with slaves of any gender without social consequence. Slaves had no legal rights to refuse. This wasn’t seen as exploitation-it was seen as a right of ownership. The sexual use of slaves reinforced social hierarchy: free men dominated, slaves submitted. This system made sexual power a visible part of daily life.

Are the Pompeii erotic paintings accurate depictions of everyday life?

No. The paintings in the Suburban Baths were likely meant for humor or fantasy, not instruction. They show exaggerated, sometimes absurd scenes-group sex, male-male acts, female-female acts-that would have been shocking even in Roman times. They reflect what Romans found amusing or taboo, not what they actually did in private. Most Romans likely followed stricter norms, especially in respectable households.

Did Romans have a concept of homosexuality?

No. Romans didn’t classify people by sexual orientation. They classified behavior by role: active or passive. A man who penetrated other men was still considered fully masculine. A man who was penetrated was seen as degraded, regardless of gender. The modern idea of “gay” or “straight” didn’t exist. Identity was tied to social status, not desire.

What happened to the original text of Philaenis?

The original text has been lost. It was likely destroyed or suppressed because it gave women authority over sexual knowledge-a threat to Roman male dominance. By the 2nd century CE, the name “Philaenis” had become a byword for obscene literature. Scholars know it existed because other writers reference it, but no fragments survive. Its absence speaks louder than any surviving text.

How did Roman sexual norms affect marriage?

Marriage was primarily about producing legitimate heirs and managing property. Sexual fidelity was expected from wives, but not from husbands. A husband could have sex with slaves, prostitutes, or male partners without penalty. A wife’s infidelity, however, could lead to divorce, loss of property, or even death. Marriage was a legal contract, not an emotional bond-and sex was its most regulated function.