For decades, we’ve been told that breaking the silence around sex-especially sexual violence-is the path to justice. But what if silence wasn’t just oppression? What if it was also a survival tactic, a shield, even a form of resistance? The truth is, sexual history isn’t written only in loud confessions. It’s written in the pauses, the metaphors, the half-sentences, and the words never spoken aloud.

The Myth of the Silent Victim

The idea that victims of sexual violence were completely silent before the 1970s is a myth. Women didn’t just sit quietly. They talked-but not the way we expect. They said things like, "I was able to handle it," or "That was just how things were back then." These weren’t denials. They were coded messages. A 2022 Stanford study of over 2,300 oral history interviews from 1938 to 1975 found that nearly 27% contained clear references to sexual harassment or assault-even though only 5% used the word "rape" or "assault." The rest used indirect language: "He made me uncomfortable," "I had to be careful," "It wasn’t what I signed up for." This wasn’t ignorance. It was strategy. Women knew that saying "no" outright could get them fired, labeled a troublemaker, or worse. So they spoke in whispers wrapped in polite language. Their silence wasn’t empty. It was full of meaning.When Saying "No" Doesn’t Work

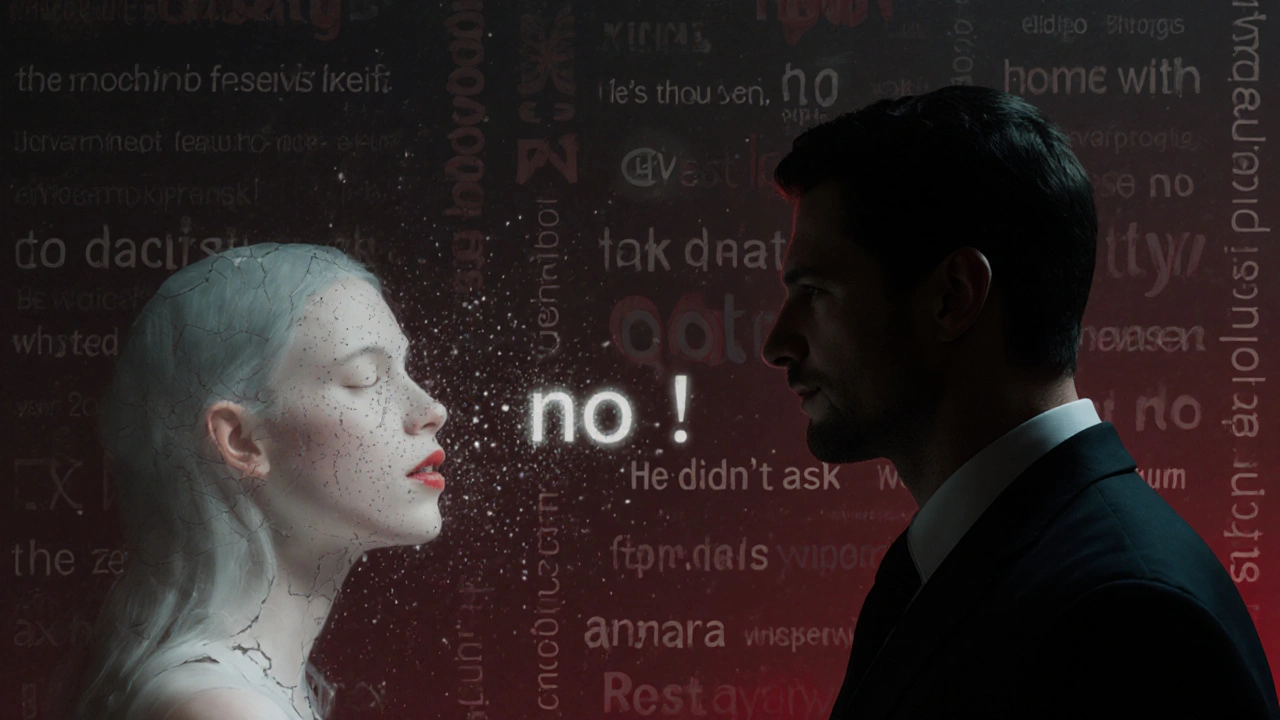

Philosopher Mary Kate McGowan’s 2005 work on speech act theory changed how we understand sexual refusal. She showed that saying "no" isn’t enough. For a refusal to count as a real speech act, someone has to hear it-and accept it as valid. In many cases, especially when pornography shaped cultural expectations, "no" was ignored. Men didn’t hear it as refusal. They heard it as part of the script. The speech act failed-not because the woman didn’t speak, but because the context poisoned her words. This isn’t just about the past. It’s still happening today. A 2023 study in the Journal of Sexual Medicine found that 68% of cervical cancer patients avoided talking about sex with their doctors because they feared being seen as "inappropriate" during illness. Even in medical settings, where trust should be high, silence wins. Why? Because the system hasn’t changed. The words are there. The willingness to speak might even be growing. But the listening? Still broken.

Silence as Resistance

Not all silence is forced. Sometimes, it’s chosen. In 2018, 14 women from the Democratic Republic of Congo refused to testify at the International Criminal Court about sexual violence. Their representative said: "Speaking within your framework would make our truth smaller than our silence." This wasn’t defeat. It was defiance. They knew the court would reduce their experiences to legal categories that didn’t fit. They refused to let their pain become a political tool. This is what scholar Maria Todorova calls "strategic silence." It’s not passive. It’s active. People choose silence when speaking would reinforce stereotypes, be twisted by institutions, or serve someone else’s agenda. In a 2021 study published in the Leiden Journal of International Law, 73% of cases where survivors declined to testify involved this exact concern: that their story would be used to justify wars, policies, or narratives they never agreed with. In communities where non-heteronormative sexuality is stigmatized, silence works the same way. A 2008 study of 87 people practicing consensual non-monogamy found that 74% altered their stories when talking to doctors. 63% left out key details from family histories. They weren’t hiding because they were ashamed. They were protecting themselves from being labeled as sick, broken, or immoral.The Grammar of Silence

Stanford researchers didn’t just collect stories. They built a tool to decode them. The Sexual Violence Linguistic Marker (SVLM) system identifies 47 specific phrases that signal sexual violence-phrases that traditional keyword searches miss. "He didn’t ask," "I didn’t know how to say no," "I just went along with it." These aren’t cries for help. They’re quiet admissions. And they’re everywhere. The SVLM system found that 31% of interviews previously labeled "no relevant content" actually contained references to sexual violence. Traditional methods failed because they looked for keywords. The new method looked for patterns-the rhythm of hesitation, the tone of normalization, the weight of a pause. This is the grammar of silence. It’s not about what’s said. It’s about how it’s said, and what’s left unsaid.