Before the internet, before cable TV, before even paperback books became common, American courts had a simple way to decide what was too dangerous to read: if a single sentence could corrupt a child, the whole book was banned. That was the Hicklin Test-a legal standard from 1868 that shaped censorship for nearly a century.

Where the Hicklin Test Came From

It started in England, in a courtroom in London. In 1868, a pamphlet called The Confessional Unmasked was seized by authorities. It was a scathing critique of Catholic confession practices, written by a former priest. The author didn’t include any explicit sex scenes. But the court didn’t care. What mattered was whether any part of the pamphlet might corrupt someone with a weak moral compass. The judge, Chief Justice Alexander Cockburn, ruled that if a publication had the tendency to deprave and corrupt those whose minds were open to such influences, it was obscene. The test was named after Benjamin Hicklin, the court official who first ordered the pamphlet’s destruction.That ruling didn’t stay in England. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court adopted it in Rosen v. United States. Suddenly, American judges were using a Victorian-era English standard to decide what Americans could read. The test didn’t ask whether the work had artistic value. It didn’t care about the author’s intent. It didn’t even look at the whole book. All it needed was one line-just one-that might harm a child or a morally vulnerable person.

How It Worked in Practice

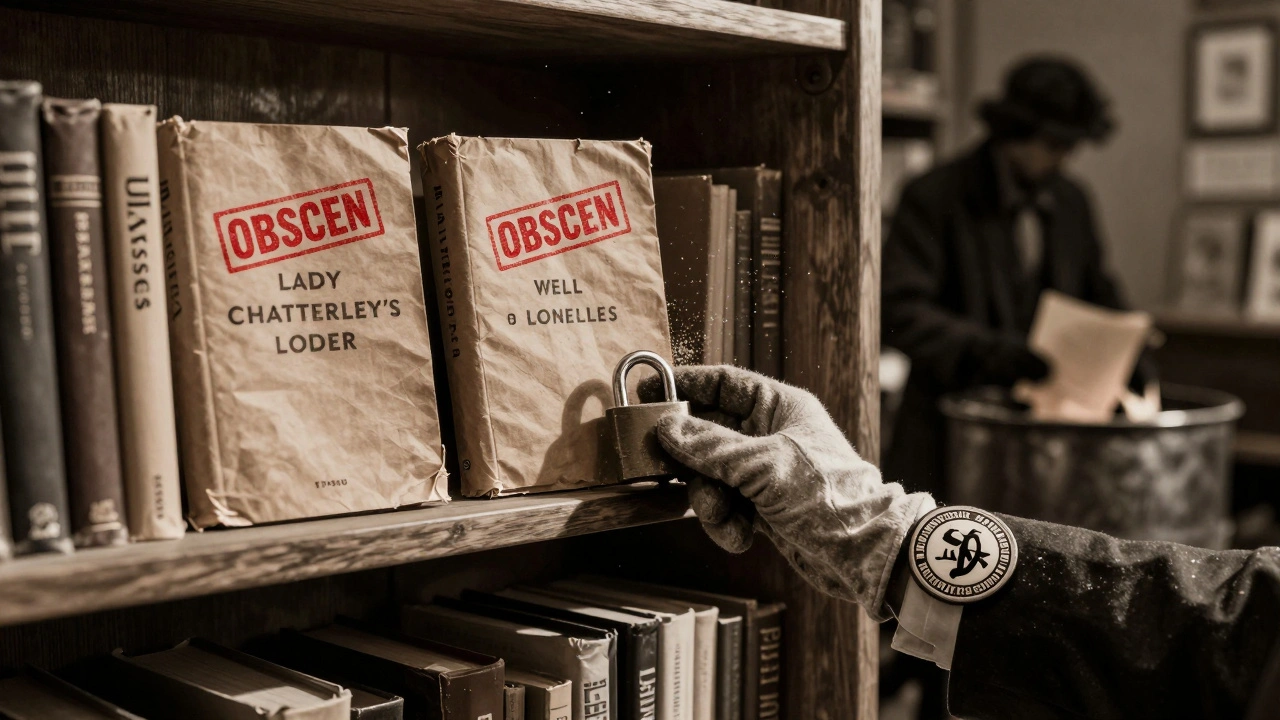

Imagine you’re a publisher in 1910 trying to print a medical textbook on human anatomy. You’ve included diagrams of reproductive organs for educational purposes. Under the Hicklin Test, all it took was one page with a clear illustration of a vagina or penis to get the entire book labeled obscene. Courts didn’t ask if the book was used in medical schools. They didn’t care if it saved lives. If a single teenager might find it shocking, the book was destroyed.This wasn’t theoretical. In 1921, Radclyffe Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness, a groundbreaking story about lesbian love, was banned in the U.S. after a judge declared its language could “deprave and corrupt” readers. The book had no explicit sex scenes. It had no pornography. But it named emotions and relationships that made some people uncomfortable. That was enough.

The same logic was used to ban James Joyce’s Ulysses, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and even books about birth control. In 1933, a U.S. judge famously ruled that Ulysses was obscene-even though the novel was widely praised by literary critics. The court focused on a few passages describing sexual thoughts. That was all it needed.

The Comstock Act and the Machinery of Censorship

The Hicklin Test didn’t operate alone. It was paired with the Comstock Act of 1873, a federal law that made it a crime to mail anything “obscene, lewd, or lascivious.” The law was enforced by Anthony Comstock, a moral reformer who became a federal agent with the power to raid bookstores, libraries, and private homes. He didn’t need a warrant. He didn’t need to prove harm. He just had to point to a passage that might corrupt someone.Over 40 years, Comstock and his agents seized about 15 tons of books and destroyed 4 million “obscene pictures.” They targeted not just pornographic magazines, but also pamphlets on contraception, sex education manuals, and even contraceptive devices sold as “medical appliances.” The ACLU later reported that over 200 medical and scientific works on human sexuality were banned between 1900 and 1950 under this system.

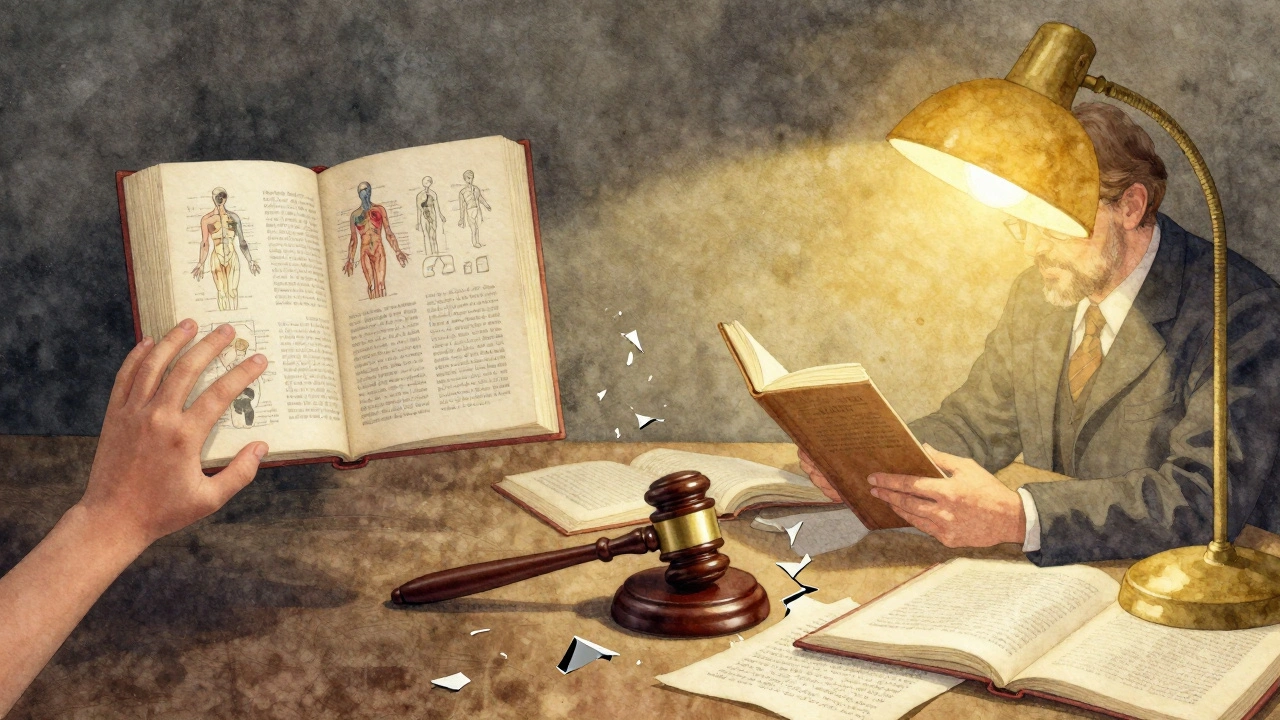

Defendants had almost no defense. Courts didn’t allow expert testimony on literature or medicine. They didn’t consider whether the material had educational value. The burden was on the publisher to prove that no one-no child, no mentally vulnerable adult-could possibly be corrupted by any part of the work. That was impossible.

Why the Hicklin Test Was Rejected

By the 1950s, the absurdity of the system was impossible to ignore. College professors couldn’t teach modern literature. Doctors couldn’t share medical information. Artists were afraid to create. In 1957, the U.S. Supreme Court finally overturned the Hicklin Test in Roth v. United States. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote that judging obscenity by its effect on the most susceptible person was “incompatible with a constitutional theory of freedom of expression.”The new standard, called the Roth Test, shifted the focus. Instead of asking whether a child might be corrupted, courts were now supposed to ask whether the average adult, applying contemporary community standards, would find the material appealed to prurient interest. And crucially, the work had to be judged as a whole-not by its worst sentence.

That standard was later refined in 1973 with the Miller Test, which added two more requirements: the material had to be patently offensive, and it had to lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. This was a massive shift. It meant that a book like Ulysses or a painting like Madonna and Child could no longer be banned just because someone found nudity shocking.

Legacy and Modern Echoes

The Hicklin Test is dead in American law. But its ghost still haunts debates about online content. When lawmakers push to ban social media posts that might “harm children,” they’re often using the same logic: if something could affect the most vulnerable, it should be removed-even if it’s harmless to adults. In 2004, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor noted that concerns about protecting kids online were “a modern echo” of the Hicklin approach.Today, the Hicklin Test is taught in law schools not as a working standard, but as a warning. It shows what happens when fear replaces judgment. When the law tries to protect people from ideas instead of empowering them to think for themselves. When a single sentence can silence a whole book.

In 2014, India became the last major country to formally reject the Hicklin Test. The Indian Supreme Court ruled it incompatible with modern constitutional values. That marked the end of a 146-year reign. But the test’s influence lingers-not in courtrooms, but in the mindset that says: if it might hurt someone, it must be stopped.

What We Lost-and What We Gained

Under the Hicklin Test, censorship wasn’t about protecting society. It was about controlling it. It silenced voices that challenged religious norms, questioned gender roles, or simply told the truth about the human body. It made literature a crime. It turned science into sin.When the test was overturned, it didn’t mean obscenity became legal. It meant the law finally recognized a basic truth: adults can read, think, and decide for themselves. The freedom to read something disturbing isn’t the same as the freedom to harm. But punishing people for what they might imagine is a step too far.

Today, we still argue about what should be allowed online. But we don’t ban books because a child might stumble on a passage. We don’t arrest doctors for teaching anatomy. We don’t burn novels because they make some people uncomfortable. That’s progress. And it came because someone finally said: the law shouldn’t protect people from ideas. It should protect their right to have them.

What was the Hicklin Test?

The Hicklin Test was a legal standard from 1868 that defined obscenity as any material that had the tendency to deprave and corrupt those whose minds were open to immoral influences. Courts could ban entire books based on a single passage, even if the work had literary, scientific, or artistic value. It focused on the most vulnerable readers-like children-rather than the average adult or the work as a whole.

When was the Hicklin Test used in the United States?

The U.S. Supreme Court adopted the Hicklin Test in 1896 and used it as the primary standard for obscenity for 61 years, until it was overturned in 1957 in Roth v. United States. During that time, it was used to ban books, medical texts, and art under the Comstock Act of 1873.

Why was the Hicklin Test considered unfair?

It ignored context, intent, and artistic merit. Prosecutors only needed to find one offensive line to ban a whole book. Authors couldn’t defend their work by explaining its purpose. Even medical textbooks on human reproduction were seized because they showed anatomy. The burden of proof was impossible: publishers had to prove that no one, not even a child, could be corrupted by any part of the material.

What replaced the Hicklin Test?

In 1957, the Supreme Court replaced it with the Roth Test, which judged obscenity based on whether the average adult, applying contemporary community standards, would find the work appealed to prurient interest. In 1973, the Miller Test added two more criteria: whether the material was patently offensive and whether it lacked serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. These tests required evaluating the work as a whole.

Is the Hicklin Test still used anywhere today?

No. The last major jurisdiction to formally reject the Hicklin Test was India in 2014, when the Supreme Court ruled it incompatible with modern constitutional rights. Today, it exists only as a historical example of overbroad censorship.