Roe v. Wade wasn’t just a court case. It was a turning point that reshaped how millions of Americans thought about their bodies, their choices, and the role of government in their lives. On January 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that a woman had a constitutional right to end a pregnancy before the fetus could survive outside the womb. That decision didn’t just legalize abortion in Texas-it overturned laws in 46 states overnight.

How It All Started

The case began with a woman named Norma McCorvey, who went by the pseudonym ‘Jane Roe.’ She was 21, pregnant, and living in Texas in 1970. Texas law made abortion illegal except when the mother’s life was in danger. No exceptions for rape, incest, or fetal abnormalities. McCorvey didn’t want the baby. She couldn’t afford to raise another child. She couldn’t travel to a state where abortion was legal. So she sued.

Her lawyers, Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee, didn’t file in state court. They knew that’s where the fight would get stuck. Instead, they filed in federal court-specifically, in the Northern District of Texas-so the case could eventually reach the Supreme Court. They teamed up with a married couple, John and Jane Doe, who wanted to use contraception but feared prosecution under Texas’s anti-contraception laws. And Dr. James Hallford, a physician who had performed abortions and was facing criminal charges.

The district court ruled that the Texas law was unconstitutionally vague and violated the Ninth Amendment, but refused to block enforcement. So the case went to the Supreme Court.

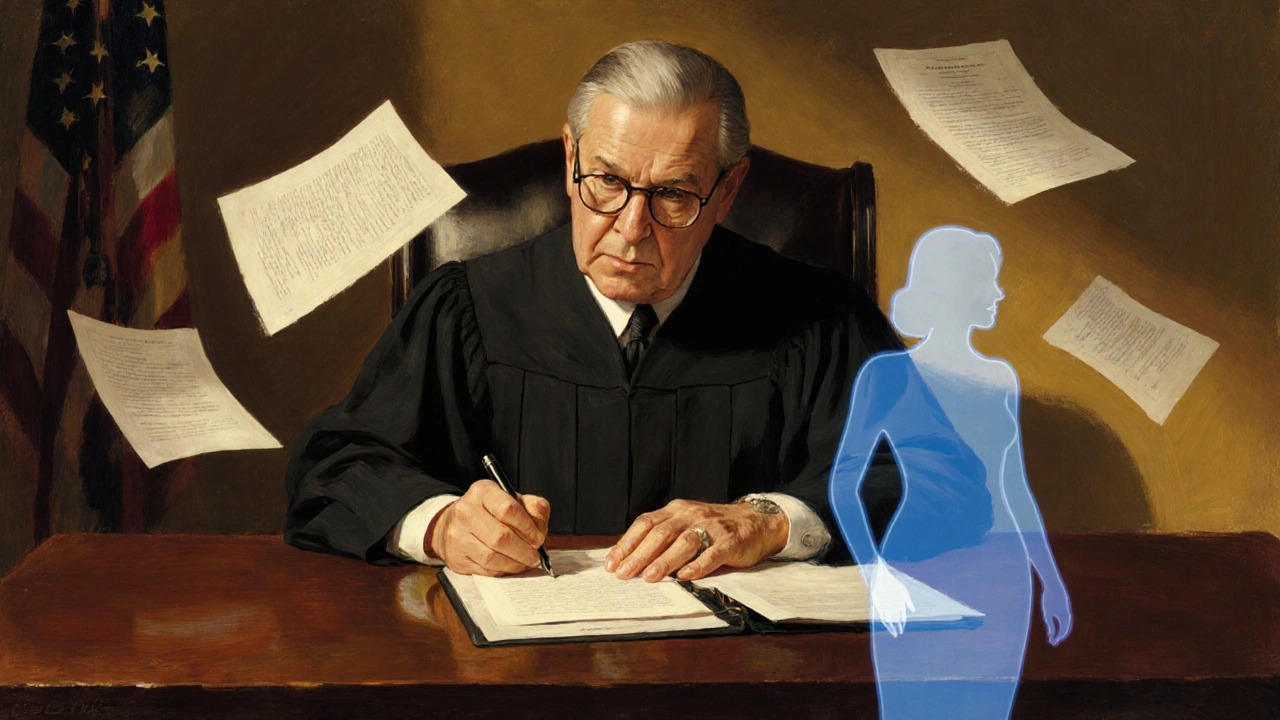

The Court’s Ruling

The Court’s opinion, written by Justice Harry Blackmun, didn’t say abortion was a ‘right’ in the way the First Amendment guarantees free speech. Instead, it found that the right to privacy-implied by the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of ‘liberty’-included a woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy.

That’s why the ruling wasn’t about when life begins. Blackmun wrote: ‘The judiciary, at this point in the development of man’s knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.’ The Court didn’t decide if a fetus was a person. It decided that the state’s interest in potential life couldn’t override a woman’s right to make her own medical choices-until the fetus could survive on its own.

To balance those interests, the Court created a three-part framework:

- First trimester (weeks 1-12): No state regulation allowed beyond requiring the procedure be done by a licensed doctor.

- Second trimester (weeks 13-24): States could regulate abortion to protect the mother’s health-like requiring clinics to meet certain safety standards.

- After viability (around 24-28 weeks): States could ban abortion, except when the mother’s life or health was at risk.

This wasn’t perfect. Critics said it was too vague. Doctors didn’t always know when viability occurred. But for nearly 50 years, it gave women a legal shield.

Who Disagreed-and Why

Two justices dissented. Byron White called the decision ‘an improvident and extravagant exercise of the power of judicial review.’ He thought the Constitution didn’t say anything about abortion, so the Court had no business inventing a right.

William Rehnquist argued that Texas’s law had been on the books since 1859, with no constitutional challenge. He believed the Court was overstepping by overriding state laws that reflected the will of voters and lawmakers.

Those dissenting voices didn’t disappear. They became the foundation for decades of legal and political strategy aimed at overturning Roe.

The Ripple Effect

After Roe, abortion became safer and more accessible. By 1980, the number of abortion-related deaths had dropped by over 90% compared to the pre-Roe era. Women no longer had to risk their lives with coat-hanger abortions or travel across state lines in secret.

But the backlash started fast. Anti-abortion groups began organizing. States passed laws to chip away at Roe-mandatory waiting periods, parental consent rules, ultrasound requirements, and clinic regulations designed to shut down providers. These were called TRAP laws-Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers. Between 2011 and 2021, states passed over 1,000 such restrictions.

By 2020, there were still 930,000 abortions in the U.S. But access was uneven. In rural areas, women often had to drive hundreds of miles. In states like Mississippi, there was only one clinic left.

The Unraveling: Dobbs v. Jackson

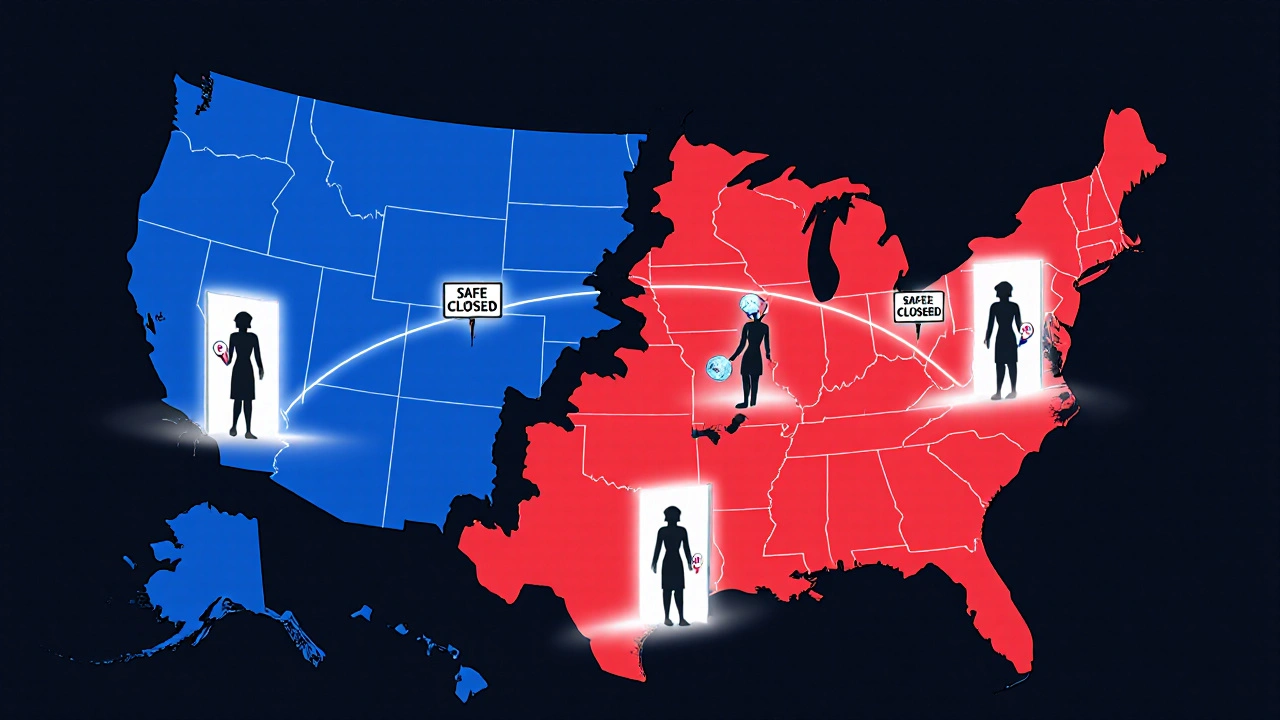

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The Court ruled 6-3 that the Constitution doesn’t mention abortion, so no such right exists. The decision returned the power to regulate abortion to individual states.

The immediate result? Fourteen states had ‘trigger laws’ that banned abortion automatically. Ten more passed new restrictions within months. At least seven women were denied emergency care for miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies because doctors feared prosecution. Hospitals in some states stopped offering even basic reproductive care.

What changed? The Court no longer recognized a constitutional right to abortion. That meant the trimester framework was gone. The ‘undue burden’ standard from Casey (1992)-which had kept Roe alive-was gone too. States could now ban abortion at any stage, even for rape or incest.

What Happens Now?

Today, abortion access depends entirely on where you live.

- In California, New York, and Illinois, abortion is protected by state law and widely available.

- In Texas, Florida, and Ohio, most abortions are banned-with narrow exceptions for the mother’s life, but not for rape or fetal anomalies.

- In states like Kansas and Michigan, voters have passed ballot measures to protect abortion rights.

Some women cross state lines. Others use medication abortion pills mailed from clinics in supportive states. But not everyone can afford the travel, the time off work, or the cost of the pills. The gap between rich and poor has widened.

The American Medical Association still says abortion is a medical decision between a patient and their doctor. But in many places, doctors are afraid to act-even when a pregnancy threatens a woman’s life.

The Legacy of Roe v. Wade

Roe v. Wade was never about ending abortion. It was about control. It said: a woman can decide what happens to her body, even if the state disagrees.

Its overturning didn’t end abortion. It just made it harder, riskier, and unequal. The number of abortions hasn’t dropped nationwide-it’s just moved. Women in restrictive states are traveling farther. Some are self-managing with pills. Others are being forced to carry pregnancies they didn’t want.

Legal scholars are still arguing over whether Roe was well-reasoned. Harvard’s Laurence Tribe called it poorly written. Yale’s Reva Siegel called it a principled defense of liberty. But one thing is clear: Roe became one of the most cited Supreme Court decisions in history-referenced in over 3,200 cases.

It didn’t just change abortion law. It changed how Americans think about rights, privacy, and the role of courts. And now, with Roe gone, the fight isn’t over. It’s just moved to statehouses, ballot boxes, and emergency rooms.