Fossil Reproduction Pattern Calculator

Determine whether fossil spacing patterns indicate sexual or asexual reproduction using evidence from Ediacaran and Cambrian fossils.

Analysis Results

For over 500 million years, life on Earth has been figuring out how to make more of itself. But how do we know what ancient creatures did in the dark, deep past when no one was around to watch? The answer lies in the rocks. Paleontologists aren’t just digging up bones-they’re reading the hidden stories of sex, reproduction, and survival written in stone. And what they’re finding is rewriting everything we thought we knew about early life.

Sex Before the Cambrian Explosion

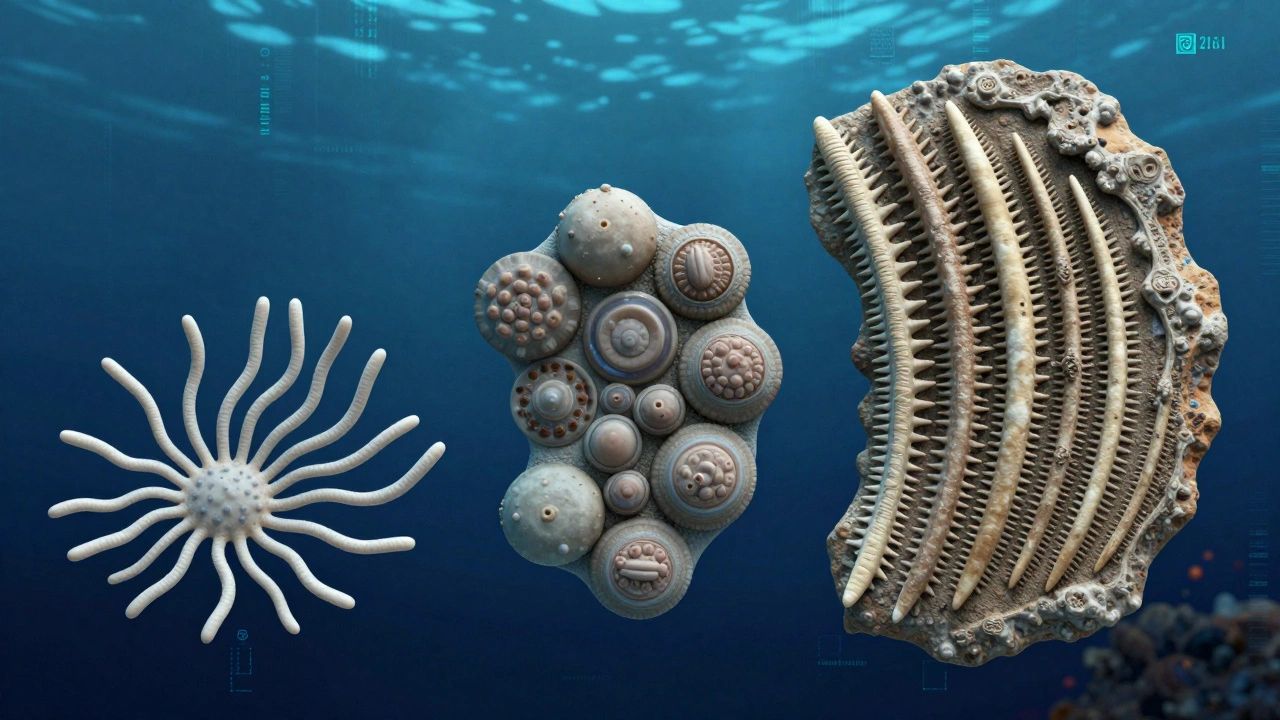

For decades, scientists assumed complex reproduction-like sexual reproduction-only became common after the Cambrian explosion, around 540 million years ago. That’s when animals with hard shells, limbs, and eyes suddenly appeared in the fossil record. But then came the Ediacaran fossils, older than any of that, dating back to 565 million years ago. These soft-bodied organisms didn’t look like anything alive today. They were frond-like, quilted, and stuck to the seafloor. Most thought they were just weird blobs with no clear biology.

Then, in 2019, a team led by Dr. Emily Mitchell at the University of Cambridge mapped over 1,500 Fractofusus fossils at Mistaken Point in Newfoundland. Using GPS with sub-centimeter precision and statistical models designed to detect clustering patterns, they found something shocking: two distinct reproductive strategies in the same species. Some fossils were scattered randomly across the rock, spaced up to 20 meters apart. That suggested they were released as floating propagules, likely carrying genetic material-strong evidence of sexual reproduction. Other fossils were tightly grouped in parent-child clusters, just 1 to 2 meters apart. That’s classic asexual reproduction through stolons, like how modern corals spread.

This wasn’t just a fluke. It meant that 565 million years ago, long before trilobites or dinosaurs, life had already evolved the ability to switch between two reproductive modes. That’s not primitive. That’s sophisticated.

How Do You Prove Sex in a Fossil?

You can’t find a fossilized mating pair. You can’t see sperm or eggs unless the conditions were perfect. So paleontologists use three main tools: spatial patterns, microscopic embryos, and isolated reproductive structures.

For sessile organisms like the Ediacaran rangeomorphs, spatial analysis is king. The nested double Thomas cluster model-developed by Mitchell’s team-compares the spacing between fossils to what you’d expect from random growth, asexual spread, or sexual dispersal. It’s like using a crime scene’s bullet trajectory to figure out where the shooter stood. If fossils are clustered in generations, it’s likely asexual. If they’re spread far apart with no clear parent-child links, it’s probably sexual.

For animals that left behind embryos, things get even more direct. In China’s Doushantuo Formation, fossils preserved in phosphate have revealed cellular details at 1.4-micrometer resolution. Scientists saw 543-million-year-old Markuelia embryos in various stages of development-some with 16 cells, others with 64-showing clear patterns of cell division. These weren’t just random blobs. They were growing like modern priapulid worms. That meant sexual reproduction was already happening, and the genetic machinery to control early development was ancient.

And sometimes, you don’t need the whole body. In 2022, researchers found Qianodus duplicis teeth-439 million years old-from a tiny, cartilaginous fish. Teeth fossilize better than bones. These teeth weren’t just for eating. Their arrangement and wear patterns suggested they were replaced in a cyclical, sequential way, just like modern sharks. That kind of tooth replacement is tied to hormonal cycles linked to reproduction. So even without a skeleton, these teeth told us about reproductive timing.

The Limits of the Fossil Record

But here’s the hard truth: most of what happened in ancient reproduction is lost. Less than 0.001% of dinosaur fossils show any direct evidence of behavior like nesting or parental care. A 2023 study found a tyrannosaur stomach with juvenile bones inside-possible evidence of cannibalism or scavenging-but even that’s debated. We can’t assume that because birds lay eggs, their ancestors did too. The oldest known amniote eggs are 250 million years old, but amniotes appeared 350 million years ago. That’s a 100-million-year gap. What happened in between? We don’t know.

And then there’s the problem of misinterpretation. In 2015, a paper claimed to find sexual dimorphism in 480-million-year-old trilobites based on size differences. Later reanalysis showed the variation fell within normal growth ranges. No dimorphism. Just growth. That’s why experts like Dr. Paul Barrett warn against guessing from shape alone. You need multiple lines of evidence.

Soft-bodied organisms are especially tricky. Their bodies decay fast. Only in rare cases-like the Burgess Shale or Doushantuo-do we get the kind of preservation that captures detail. And even then, taphonomy-the science of how fossils form-can distort everything. A fossil might look like a reproductive structure, but it could just be a mineral deposit. That’s why modern methods like synchrotron X-ray tomography are so critical. They let scientists see inside the rock without breaking it open.

Technology Is Changing Everything

Twenty years ago, this field was mostly guesswork. Now, it’s data-driven. A single Ediacaran mapping project requires a team of three to four people, high-end GPS units costing $30,000, laser scanners, and months in remote, rugged terrain. One field season at Mistaken Point can cost over $150,000.

But the payoff is huge. In 2024, a team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences found fossilized sperm cells-550 million years old. Using synchrotron radiation, they mapped the structure at half-a-micrometer resolution. These weren’t just blobs. They had tails, heads, and movement patterns. The oldest direct evidence of sexual reproduction ever found.

And now, machine learning is stepping in. In December 2023, researchers at the University of Bristol trained an AI to recognize reproductive clusters in partial fossil assemblages. It got 96.7% accuracy. That means you don’t need a complete fossil bed to make a strong inference. You can piece together the story from fragments.

The future? The PaleoRepro Project, launched in February 2025, is a $14.7 million global effort to combine spatial mapping, embryology, and geochemistry across 12 key fossil sites. The goal: build a database of reproductive strategies across 600 million years of life.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just about old bones. It’s about understanding how complexity evolves. If life could switch between sexual and asexual reproduction 565 million years ago, then the pressure to evolve complexity wasn’t waiting for the Cambrian. It was already there, shaping life long before hard shells or eyes appeared.

It also changes how we think about evolution. We used to see it as a slow march from simple to complex. But the fossil record of sex tells us: complexity can appear early, disappear, and reappear. It’s not linear. It’s messy. It’s opportunistic.

And for the first time, we’re not just guessing. We’re measuring. We’re modeling. We’re seeing the patterns in the rocks, and they’re telling us that sex-real, genetic, complex sex-wasn’t a late invention. It was one of the first big ideas life ever had.

What’s Next

The biggest threat isn’t lack of data-it’s loss of sites. Coastal erosion at Mistaken Point is eating away 2.3 meters of rock every year. That’s 2.3 meters of 565-million-year-old history, gone forever. Without urgent preservation, we may lose the best window we have into early reproduction.

Meanwhile, new techniques are emerging. Researchers are testing for preserved proteins in dinosaur eggshells. Others are looking for chemical traces of hormones in fossilized tissues. The line between paleontology and molecular biology is blurring.

One thing is certain: the story of sex in deep time is just beginning. And every fossil, every cluster, every microscopic embryo is another piece of a puzzle that’s older than any animal alive today.