Sexuality Diagnosis History Checker

Explore the medicalization timeline

Select a sexual identity or behavior to see when it was classified as a disorder and when it was removed from diagnostic manuals.

Before the 1800s, same-sex desire, unusual sexual behaviors, or low libido weren’t seen as medical problems. They were sins, crimes, or moral failings. Then, something shifted. Doctors, researchers, and clinics began to claim authority over what was normal and abnormal in human sexuality. This wasn’t just about treating illness-it was about defining who people were. The medicalization of sexuality turned identities into diagnoses, and those diagnoses changed lives.

The Birth of Sexology: When Doctors Took Over

In the mid-1800s, as churches lost influence in public life, medicine stepped in. German physician Iwan Bloch didn’t just study sex-he created a new field: sexology. In 1907, he called it the scientific study of sexual life from a medical and social perspective. That label gave doctors permission to talk about sex in ways no one had before. And they didn’t just observe-they classified. Magnus Hirschfeld opened the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin in 1919. It was the first clinic in the world dedicated entirely to sexual health. People came with questions about their desires, their bodies, their identities. Hirschfeld’s team gave them medical documents that could protect them from arrest or persecution. For some, that was life-changing. But it also meant their identities were now tied to a doctor’s diagnosis. Being a homosexual wasn’t just about who you loved-it became a medical category, labeled as a ‘congenital inversion’ by even the most progressive thinkers of the time.The DSM: The Rulebook That Defined Normal

In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association released the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM. It didn’t just list symptoms-it listed people. Homosexuality was labeled a ‘sociopathic personality disturbance.’ That wasn’t an accident. It was policy. For decades, therapists used this manual to justify electric shocks, chemical castration, and talk therapy aimed at ‘curing’ gay people. The DSM didn’t just punish difference-it created new identities. Before the 1950s, people didn’t think of themselves as ‘lesbians’ or ‘transgender.’ They were women who loved women, or people who felt trapped in the wrong body. The DSM turned those feelings into disorders. By the 1980s, the DSM-III had 22 categories of ‘psychosexual disorders.’ Everything from ‘fetishism’ to ‘inhibited sexual desire’ was now a clinical condition. It wasn’t until 1973, after years of protests from LGBTQ+ activists, that homosexuality was removed from the DSM. But the damage was done. Millions had been told they were sick. Many believed it.From Morality to Physiology: The Masters and Johnson Effect

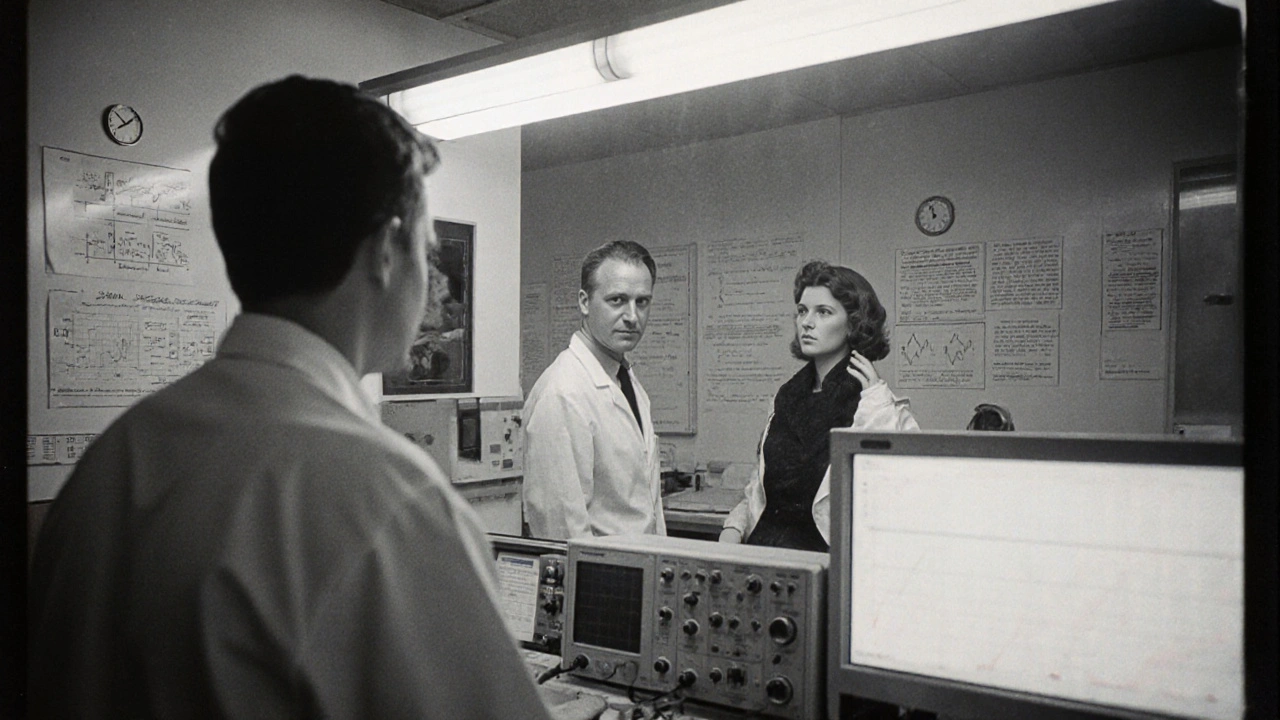

In 1966, William Masters and Virginia Johnson published Human Sexual Response. They studied over 10,000 orgasms in a lab. Their findings were groundbreaking: sex had a predictable cycle-excitement, plateau, orgasm, resolution. It sounded scientific. And it became the new standard. Suddenly, if someone didn’t follow that cycle, they had a ‘dysfunction.’ If a woman didn’t get aroused easily, she had ‘hypoactive sexual desire disorder.’ If a man couldn’t maintain an erection, he had ‘erectile dysfunction.’ These weren’t just labels-they were medical problems that needed treatment. Clinics opened. Drugs were developed. The pharmaceutical industry saw opportunity. The shift from moral failure to medical condition seemed progressive. But it didn’t free people-it replaced one kind of control with another. Now, instead of being judged by priests, people were judged by doctors using a rigid physiological model. Desire that didn’t fit the cycle? Pathological. Sex that didn’t follow the script? Broken.

The Rise of the Sexual Medicine Clinic

By 2020, there were 217 certified sexual medicine clinics in the U.S. Each required doctors to complete 120 hours of specialized training through the American Board of Sexual Medicine. These weren’t just fertility clinics or STD centers. They were places where people went to fix their sexuality. Medical schools picked up the trend. By 2019, 89% of U.S. medical schools taught sexual health using the same frameworks from Masters and Johnson. Students learned to diagnose ‘dysfunctions’ before they learned to talk about consent or pleasure. And patients? They came in hoping for help-and often left with a label. A 2017 study in the Journal of Homosexuality found that 68% of LGBTQ+ people had negative experiences with healthcare providers who applied outdated medical models. Some were told their identity was a disorder. Others were pushed into conversion therapy. One woman told researchers she was diagnosed with ‘hypoactive sexual desire disorder’ after saying she didn’t want sex often. She didn’t feel distressed-she felt fine. But the doctor said she needed treatment.Pharma and the Business of Desire

When Viagra hit the market in 1998, it didn’t just treat erectile dysfunction-it created a market. By 2005, global sales hit $4.3 billion. Companies saw a pattern: if you can convince people their natural desires are broken, you can sell them a fix. The push for female sexual dysfunction drugs was even more aggressive. Between 2000 and 2010, pharmaceutical companies spent $4.2 billion developing treatments for low female desire. The drug flibanserin (Addyi) was approved by the FDA in 2015 after two rejections. It worked for about 1 in 3 women. It caused dizziness, nausea, and fainting. And yet, it made $17.3 million in its first year. A 2020 study from the Kinsey Institute found that 73% of women who took Addyi still saw themselves as ‘dysfunctional’ even after stopping the drug. The diagnosis stuck. The label outlasted the pill. Industry spending on sexual medicine research jumped 214% between 2010 and 2020. Most of that money went to female sexual dysfunction-even though the market was smaller than the male market. Why? Because the medical model made it profitable to pathologize desire.

Who Gets Pathologized? Who Gets Saved?

Medicalization didn’t treat everyone equally. Transgender people were especially vulnerable. For decades, gender identity was classified as a mental disorder. Even after the WHO removed ‘gender identity disorder’ from its diagnostic manual in 2019 and replaced it with ‘gender incongruence’ under sexual health, many doctors still confused gender with sexuality. A 2020 study in the American Journal of Public Health found that transgender people were 3.2 times more likely to be misdiagnosed. Over half reported being denied gender-affirming care because their provider thought their identity was a sexual disorder. Meanwhile, same-sex relationships among women in the 1800s-called ‘romantic friendships’-were erased by the medical label of ‘lesbian.’ What had been socially accepted affection became a clinical category tied to deviance. The same happened with men. Before the 1900s, men who had sex with men weren’t seen as a different kind of person-they were men who did something. The medical model turned them into a type of person. And that change stuck.The Pushback: When Experts Started Questioning the System

Not everyone agreed. Dr. Leonore Tiefer, a psychologist and critic of sexual medicine, spent decades arguing that low desire in women wasn’t a disease-it was a normal variation. She called the push for female Viagra a ‘medical scam.’ In 2018, the Citizen’s Commission on Human Sexuality formed. They lobbied the American Medical Association. In 2021, the AMA passed Resolution 305, acknowledging that pathologizing normal sexual variations causes harm. The DSM-5-TR in 2022 removed or merged several outdated categories. Paraphilias were still there, but the number of sexual disorders dropped by 37% since the DSM-III. Experts are now debating whether any sexual variation should be labeled a disorder at all. The World Health Organization’s 2023 Global Strategy on Human Sexual Health now explicitly recommends ‘depathologization of sexual orientations and gender identities.’ That’s a big deal. It means the global medical community is starting to say: some things aren’t broken. They just aren’t normal according to a 1950s lab.What’s Left?

Today, you can buy an app that tells you if your libido is ‘normal.’ You can get a prescription for a pill that makes you want sex more. You can be told your identity is a diagnosis. But you can also walk into a clinic and be heard without being judged. The medicalization of sexuality gave us language to talk about things that were once silenced. It gave some people access to care, protection, and even legal rights. But it also turned intimacy into a checklist, desire into a metric, and identity into a disorder. The question now isn’t whether medicine should be involved in sexuality. It’s: who gets to decide what’s normal? And whose lives are we fixing-or erasing-in the process?Was homosexuality ever really considered a mental illness?

Yes. From 1952 until 1973, homosexuality was listed as a mental disorder in the DSM. It was classified as a ‘sociopathic personality disturbance,’ then later as a ‘sexual deviation.’ This classification justified forced treatments like electroshock therapy and chemical castration. It wasn’t removed because science proved it was wrong-it was removed because activists pressured the psychiatric establishment to change. Even after removal, many doctors continued to treat it as a disorder for years.

How did Masters and Johnson change how we think about sex?

Masters and Johnson turned sex into a measurable physiological process. Their four-phase model-excitement, plateau, orgasm, resolution-became the standard for diagnosing sexual problems. If someone didn’t follow that cycle, they were labeled with a dysfunction. Their work made sex seem scientific, but it also made natural variations in desire, arousal, or timing seem like medical failures. Their lab-based model ignored emotion, context, culture, and consent, but it became the foundation of modern sexual medicine.

Are sexual dysfunction diagnoses still used today?

Yes, but they’ve changed. The DSM-5 replaced ‘hypoactive sexual desire disorder’ with ‘female sexual interest/arousal disorder’ in 2013, partly because the old term was too vague and often misapplied. But the core idea remains: if your desire doesn’t match a clinical norm, it’s a disorder. Critics argue these diagnoses still pathologize normal differences, especially in women and older adults. Newer versions like the DSM-5-TR have reduced the number of categories, but the medical framework persists.

Why did pharmaceutical companies invest so much in female sexual dysfunction drugs?

Because they saw a market. While the male erectile dysfunction market was huge, the female market was seen as untapped. Companies spent billions promoting the idea that low desire in women was a treatable disease. Drugs like flibanserin (Addyi) were approved despite weak evidence and serious side effects. Marketing framed it as a ‘female Viagra,’ even though the biology is completely different. The goal wasn’t just health-it was profit. And it worked: billions were made, and millions of women were told their natural libido was broken.

Can medicalization ever be helpful?

Yes, but selectively. Medicalization helped people with real physical conditions like erectile dysfunction due to diabetes or pain during sex from endometriosis. It gave them access to treatment and reduced stigma. It also helped some LGBTQ+ people in the early 20th century by giving them medical documentation that protected them from arrest. The problem isn’t medicine itself-it’s when medicine defines normal human variation as disease. The best approach today is to treat actual dysfunction while respecting identity, desire, and autonomy as natural, not pathological.

What’s the future of sexual medicalization?

There’s growing tension. On one side, digital health apps and pharmaceutical companies are pushing more medical labels for things like ‘digital porn addiction’ or ‘low sexual satisfaction.’ On the other, researchers and activists are calling for depathologization. A 2022 survey found 62% of sexuality experts believe diagnostic categories for sexual variations will be eliminated in the next 15 years. The WHO’s current stance supports this shift. The future likely lies in separating real medical conditions from social norms-treating what hurts, not what doesn’t fit.