Sex Education Impact Calculator

Impact Calculator

Projected Outcomes

Teen Pregnancy: 0 cases

Venereal Disease: 0 cases

Based on Guttmacher Institute research: Comprehensive programs reduce teen pregnancy by 50% compared to abstinence-only approaches. Historical data from the 1955 AMA series showed 22% teen pregnancy reduction and 37% STD reduction.

Before the 1950s, most American students learned about sex from whispers, biology textbooks, or the occasional lecture by a visiting doctor. Schools rarely talked about it. When they did, it was often just about avoiding disease-no mention of relationships, contraception, or emotions. Then, in 1955, everything changed. The American Medical Association and the National Education Association released a five-part series of pamphlets that became the first nationwide standard for sex education in U.S. public schools.

The Problem Before the Series

In the 1920s, only 20% to 40% of schools offered any kind of sex education. What little existed was scattered and inconsistent. Some districts used posters. Others had doctors come in for a single assembly. The 1918 Chamberlain-Kahn Act had pushed venereal disease education for soldiers during World War I, but that didn’t translate to classrooms. By the early 1950s, public health officials were alarmed. Post-WWII data showed 11% of military recruits had contracted venereal diseases. Teen pregnancy rates were rising. Schools had no clear guidelines. Parents were confused. Teachers were untrained. The country needed a unified approach.The Five Pamphlets That Changed Everything

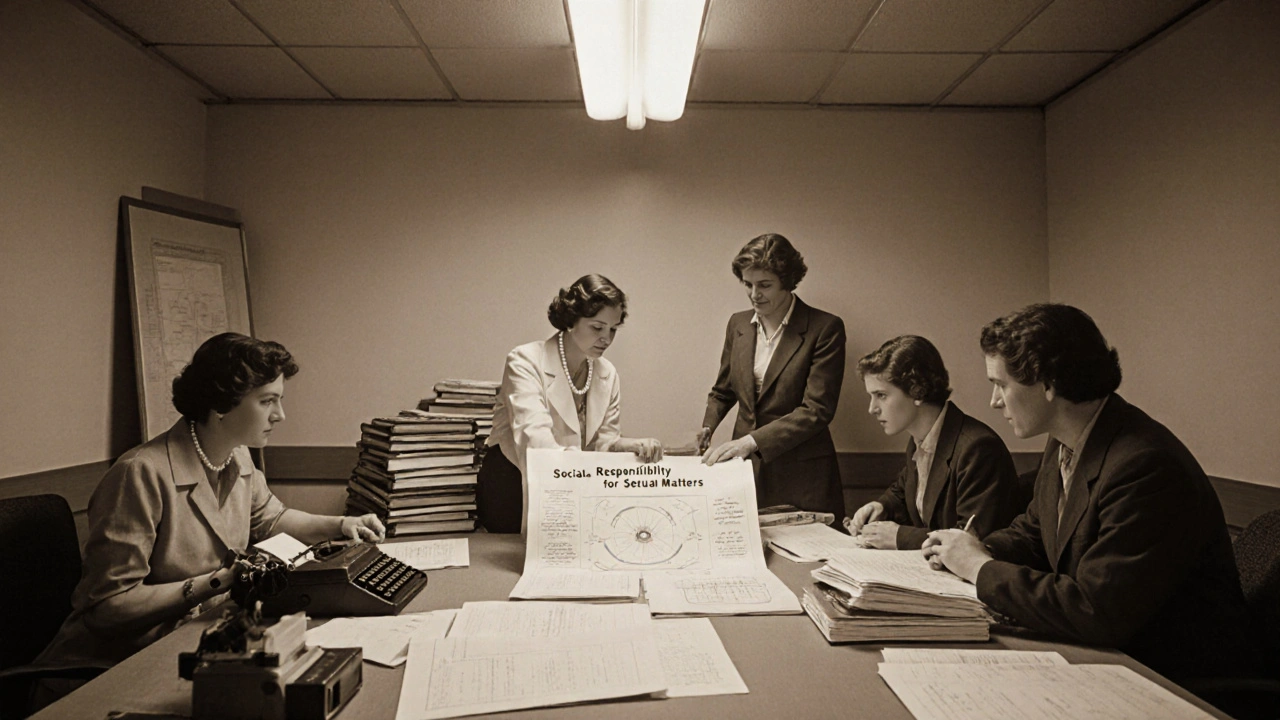

The AMA’s series wasn’t just another pamphlet. It was a full curriculum. Five titles covered everything from biology to ethics:- Understanding Growth and Development

- Personal Health and Hygiene

- Marriage and Family Living

- Prevention of Venereal Disease

- Social Responsibility in Sexual Matters

How It Was Rolled Out

The government didn’t just hand out the pamphlets. They built a system. $2.3 million in federal grants-about $25 million today-funded the printing and distribution of 1.2 million copies. Every public school in the 48 states received them. But the real innovation was training. Teachers had to complete 40 hours of specialized instruction before they could teach the material. That was unheard of. Before this, most educators had no formal training in human sexuality. Now, they had manuals, lesson plans, and even sample letters to send to parents. Schools were told to start with 7th grade and build up over six years. They were expected to spend 15 to 20 hours total per student. Districts had to keep records of what was taught and who participated. By 1957, 85% of U.S. high schools were using the materials. That’s a massive jump from the 40% of schools offering any sex ed in the 1920s.

What Worked-and What Didn’t

The results were clear. A Harvard study tracking 15,000 students from 1956 to 1960 found a 22% drop in teenage pregnancy rates and a 37% decline in reported venereal diseases among teens who received the full curriculum. Teachers loved it. A 1957 NEA survey showed 78% of educators said the materials were clear, accurate, and age-appropriate. Urban schools embraced it. Rural areas? Not so much. In Mississippi, Alabama, and other parts of the Bible Belt, parents pulled their kids out of class. Churches handed out flyers warning that the series would “corrupt the morals of our youth.” A 1958 letter from a Mississippi principal said 47% of parents requested exemptions. A Gallup poll that same year showed 72% support in Northeastern cities-but only 31% in rural Southern towns. The John Birch Society called it “moral relativism.” The National Catholic Welfare Conference published a 47-page critique accusing the series of undermining parental authority. The Southern Baptist Convention passed a resolution urging churches to resist it. But here’s the twist: the materials weren’t pushing sex. They were pushing facts.The Hidden Gaps

The AMA series was groundbreaking-but not perfect. It assumed all students were straight. There was no mention of same-sex relationships. LGBTQ+ students were invisible in the curriculum. That wasn’t an accident. The 1950s were not a time for open discussion of sexual orientation. The materials reflected the norms of the era, even as they broke new ground in other areas. Also, the series didn’t address race or class. It was designed for a mostly white, middle-class audience. Schools in poor or segregated districts often lacked the resources to implement it fully. Visual aids were recommended but rarely available in rural areas. Only 63% of schools had access to them. Still, for the time, it was revolutionary. Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone, who later led Planned Parenthood, said the AMA series helped her convince the medical community that doctors should be allowed to give out birth control information. The Journal of the American Medical Association called the series “the medical profession’s formal recognition that ignorance about human sexuality constitutes a significant public health hazard.”