Ancient Funerary Practices Comparison

Etruscan

Sex was sacred ritual

Erotic scenes on tomb walls

Women held property and participated actively

Sexual acts as spiritual transition

Death seen as journey, not end

Art reflected community, not just individuals

Greek

Sex rarely shown in tombs

Women depicted as virgins, distant

Focus on restraint and modesty

Death seen as final separation

Funerary art focused on ideals

No erotic imagery in elite burials

Roman

No explicit erotic imagery

Death as dignified transition

Focus on lineage and status

Women less visible in public

Emperor depictions as gods

Sex viewed as vulgar in funerary context

Key Differences: Etruscan vs Greek vs Roman

| Etruscan | Greek | Roman | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex in Funerary Art | Explicit erotic scenes | Rare or absent | Rare or absent |

| Gender Roles | Women active participants | Women distant, passive | Women less visible in public |

| View of Death | Transition to afterlife | Final separation | Dignified transition |

| Spiritual Significance | Sex as sacred ritual | Not connected to death | Not connected to death |

| Women's Agency | Property ownership, public presence | Limited public role | Limited public role |

| Cultural View | Pleasure as sacred | Restraint as virtue | Dignity as priority |

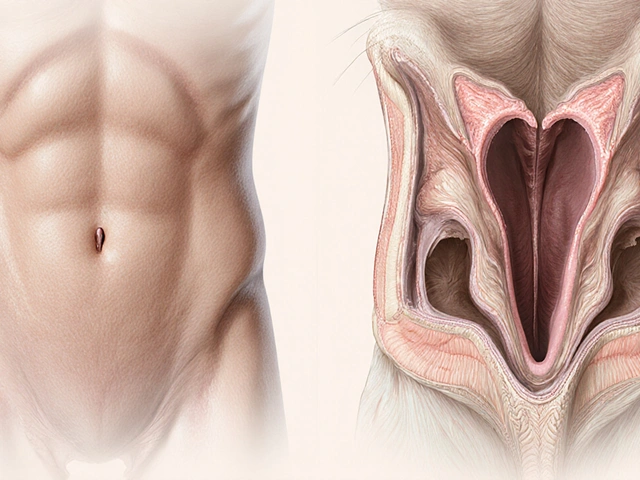

When you think of ancient tombs, you probably imagine quiet, solemn spaces-stone carvings of gods, rows of names, maybe a few offerings left behind. But in Etruria, around 2,500 years ago, the dead weren’t buried in silence. They were surrounded by erotic scenes-naked bodies entwined, couples embracing, men and women engaged in acts that would make even modern viewers pause. These weren’t random decorations. They were sacred. They were maps.

Death Wasn’t the End-It Was a Transition

The Etruscans didn’t see death as a final stop. They saw it as a journey. And like any journey, it needed preparation. Their tombs weren’t just burial chambers; they were ritual spaces designed to guide the soul from life into the afterlife. Paintings on the walls showed dancing, feasting, wrestling, and yes-sex. These weren’t just celebrations of life. They were tools. Professor Rasmus Brandt, who has spent 30 years studying Etruscan tombs in Italy, argues that the moment of orgasm was central to this transition. At that peak, he says, you’re no longer fully in your body. You’re in a trance. That altered state, he believes, allowed the dead to cross into the realm of the spirits. The Etruscans didn’t just depict sex-they used it as a ritual technology. The physical act mirrored the soul’s release from the body. This isn’t just theory. It’s written into the art. In the Tomb of the Bulls, painted around 540 BCE in Tarquinia, two men and a woman are shown in a complex, intimate formation. One man kneels on his forearms, the other penetrates the woman from behind. The positioning isn’t random-it’s deliberate. The bodies are arranged to suggest movement, energy, a kind of sacred chaos. This wasn’t pornography. It was liturgy.Sex Wasn’t Taboo-It Was Sacred

Compare this to ancient Greece. Athenian funerary art rarely showed couples together. Women were depicted as virgins, holding lotus buds-symbols of unfulfilled marriage. The dead were remembered as pure, silent, and distant. The Etruscans did the opposite. They celebrated union. Take the sarcophagus of Larth Tetnie and Thanchvil Tarnai from Vulci, dated to the late 4th century BCE. The husband and wife lie naked under a thin blanket. Their bodies are so precisely carved you can see their thighs touching. Her hand is sliding downward. The artist didn’t hide the intimacy. They highlighted it. This wasn’t about lust. It was about continuity. The act of sex, in death as in life, was a force that connected worlds. And women weren’t passive in this. Etruscan women held property, kept their own names, and sat beside men at banquets. In the Tomb of the Triclinio, painted around 470 BCE, women are shown drinking wine, playing music, and dancing with men. Roman writers like Theopompus were shocked. To them, this was decadence. To the Etruscans, it was normal. Women weren’t just present-they were active participants in rituals that bridged life and death.More Than Just Heterosexuality

The sexual scenes in Etruscan tombs aren’t limited to men and women. Homosexual acts appear frequently. In the Tomb of the Flogging, one man is penetrated while another penetrates a woman, all while a third beats her with a riding crop. It’s violent. It’s intense. And it’s not meant to shock-it’s meant to convey power, control, transformation. Scholar Alessandro Naso calls this an “erotic S&M threesome,” but he doesn’t interpret it as punishment. He sees it as a ritual of release. The pain, the pleasure, the physical extremes-all were ways to break through the barrier between worlds. Modern labels like “gay” or “bisexual” didn’t exist then. The Etruscans weren’t categorizing people. They were mapping states of being. Even the tools used in these scenes matter. The riding crop, the wine cups, the jewelry-these weren’t props. They were ritual objects. The same gold necklaces found on women in tombs were also found in temple deposits at Poggio Colla, showing that women’s ritual roles extended beyond death.

Why Did They Do This? Three Theories

Scholars don’t all agree on what these scenes meant. Three main interpretations have emerged:- Ritual Transition (Brandt): Orgasm was a spiritual gateway. The body’s peak moment mirrored the soul’s departure. The act itself was a form of hypnotic trance that helped the dead navigate the dark forces of the afterlife.

- Celebration of Life (Naso): Sex was a defiant act against death. By showing pleasure, movement, and connection, the Etruscans refused to let death have the last word. Death wasn’t feared-it was met with vigor.

- Humor and Symbolism (Whitehead): Some scenes may have been playful, even absurd. The Etruscans weren’t always serious. A man being licked by a dog while a woman watches? That might have been a joke. But even jokes can carry meaning.

How This Changed Over Time

These depictions didn’t appear overnight. They evolved. From the Orientalizing period (720-580 BCE) through the Hellenistic era (323-31 BCE), 83% of painted tombs included some form of erotic imagery, according to Ingrid Edlund-Berry’s 2023 synthesis of 37 excavations. The earliest scenes were simpler-couples embracing. Later, they became more complex: group acts, use of props, even animal figures like the lions in the Tomb of the Lioness, who stand guard over dancers and lovers. In the 19th century, many scholars tried to ignore or cover up these images. Victorian morals made them uncomfortable. But since the 1980s, the field has changed. Today, researchers use multispectral imaging to reveal hidden pigments. In 2021, scans of the Tomb of the Bulls uncovered genitalia that had faded beyond human sight. The original paintings were even more explicit than we thought. This isn’t just academic curiosity. In 2023, the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage allocated €2.3 million to preserve and study these tombs. The Corpus of Etruscan Tomb Paintings now has a dedicated volume (Volume VII) for erotic scenes. The field is growing-87 publications on Etruscan sexuality appeared between 2000 and 2023, up from just 12 before 1980.

What This Tells Us About Etruscan Society

The presence of these scenes tells us something fundamental: the Etruscans saw sex as deeply spiritual. It wasn’t separate from religion-it was part of it. Death wasn’t something to mourn quietly. It was something to face with fullness-emotion, sensation, connection. Their women had agency. Their bodies were open. Their rituals embraced the physical. And their art didn’t shy away from the raw, messy, powerful reality of being alive-even when facing death. Compare this to Rome, which later absorbed Etruscan territory. Roman funerary art was restrained. Emperors were shown as gods. Families were depicted in formal poses. Sex? Not in tombs. The Romans saw Etruscan practices as wild, excessive, even dangerous. But maybe they were just afraid of what the Etruscans knew: that pleasure and death are two sides of the same coin.Why This Still Matters Today

We still struggle with how to talk about sex and death. We bury our dead in silence. We avoid the body. We pretend death is clean, quiet, and distant. The Etruscans didn’t. They painted their tombs with sweat, skin, and desire. They understood that the moment of orgasm-like the moment of death-is a threshold. One ends the body. The other ends the soul’s attachment to it. Their art reminds us that rituals don’t have to be solemn to be sacred. Sometimes, the deepest truths are found not in silence, but in the wild, messy, beautiful act of being human.Today, researchers are comparing Etruscan tomb scenes to Moche sex pots from ancient Peru. Both cultures linked sex and death. Both used erotic imagery to guide the soul. This isn’t coincidence. It’s a pattern-one that challenges our modern assumptions about what ancient people believed.

Why were sexual scenes common in Etruscan tombs but not in Greek or Roman ones?

Etruscan society valued sexual intimacy as part of spiritual life, especially in the transition to death. Greek and Roman cultures, especially in Athens and later Rome, emphasized restraint, public modesty, and the separation of sex from religious ritual. Greek funerary art often showed idealized, chaste figures, while Romans focused on lineage and social status. Etruscans, by contrast, saw sex as a sacred act that mirrored the soul’s release, making it central to their burial customs.

Did Etruscan women have more freedom than women in other ancient cultures?

Yes. Etruscan women kept their birth names, owned property, participated in public banquets, and were depicted in art alongside men in intimate and active roles. This contrasted sharply with Athenian women, who were largely confined to the home and rarely shown in funerary art. Roman observers were so surprised by Etruscan women’s visibility that they labeled them as decadent. Archaeological finds, like gold jewelry from Poggio Colla, confirm women’s active roles in both domestic and ritual life.

Were these sexual scenes meant to be real rituals or just symbolic art?

Evidence suggests both. The scenes were painted on tomb walls as symbolic guides for the soul’s journey, but they may also reflect actual ritual practices. Professor Rasmus Brandt argues that participants in funerary rites may have engaged in ecstatic or erotic acts to induce trance states, helping the deceased cross into the afterlife. The consistency of these images across centuries and multiple sites supports the idea that they were part of lived religious practice, not just decoration.

How do we know these scenes weren’t just about hedonism or decadence?

Roman writers like Theopompus called Etruscans hedonists, but that was a biased outsider view. The scenes appear in tombs alongside other ritual symbols-dancers, lions, banquets, and processions-suggesting they were part of a broader cosmology. The precision of the depictions, the inclusion of specific positions and tools, and their presence in elite burials over 400 years point to deep ritual meaning, not casual indulgence. Modern scholars reject the idea that these were simply “party scenes.”

Are there any modern parallels to Etruscan sexual funerary art?

Yes. The Moche culture of ancient Peru created pottery depicting explicit sexual acts alongside scenes of death and sacrifice, suggesting a similar link between sexuality and the afterlife. Other cultures, like certain Hindu tantric traditions, also use sexual symbolism to represent spiritual union. These parallels show that the connection between sex and transcendence isn’t unique to Etruria-it’s a recurring theme in human attempts to understand death.

Why did Etruscan erotic art disappear after Roman conquest?

As Rome absorbed Etruria, Roman cultural norms replaced Etruscan ones. Romans viewed explicit sexual imagery as vulgar, especially in funerary contexts. Their own burial practices emphasized dignity, lineage, and restraint. With Roman dominance came suppression of Etruscan religious practices, including those involving erotic ritual. The tombs were sealed, forgotten, and only rediscovered centuries later-when modern archaeology began to look beyond moral judgments.