AIDS Drug Cost Impact Calculator

How ACT UP Changed Drug Prices

Before ACT UP, the only approved AIDS drug AZT cost $10,000 per year (over $26,000 today). After their Wall Street protest, Burroughs Wellcome lowered the price by 20%. This calculator shows the financial impact of this action.

Impact Analysis

ACT UP's Impact: This calculation shows just one of many victories. When ACT UP protested the FDA, approval time for AIDS drugs dropped from 6-7 years to 1.2 years, saving an estimated 14 million lives.

Remember: These price drops weren't charity—they were demands made by people who were dying. As Larry Kramer said: "We're not asking for help anymore. We're taking it."

Civil disobedience didn’t start with the civil rights movement-it didn’t even end there. In the late 1980s, as AIDS killed thousands and the government looked away, a new kind of protest rose from the ashes of grief and rage. People who were dying, their lovers, their friends, their families-none of them waited for permission to speak up. They took to the streets, locked themselves to buildings, lay down in traffic, and refused to be silent. This was ACT UP: the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power.

They Didn’t Ask for Permission

On March 12, 1987, Larry Kramer stood in a small community center in New York City and shouted at a room full of angry, grieving people: "We’re not asking for help anymore. We’re taking it." That night, 300 people formed ACT UP. They didn’t have a budget. They didn’t have political connections. They had nothing but their bodies, their rage, and a single, terrifying truth: if no one acted, they would all die. The government wasn’t just slow-it was actively hostile. The CDC didn’t even include women in its official AIDS definition until 1993. Insurance companies denied coverage. Hospitals turned patients away. Politicians like Senator Jesse Helms called AIDS a "punishment for sin." Meanwhile, the drug Burroughs Wellcome charged $10,000 a year for AZT-the only approved treatment. That’s over $26,000 today. People were paying rent with their life savings just to stay alive a few more months. ACT UP’s answer? Direct action. No petitions. No lobbying. No polite meetings. They targeted the people and institutions responsible.Wall Street, St. Patrick’s, and the FDA

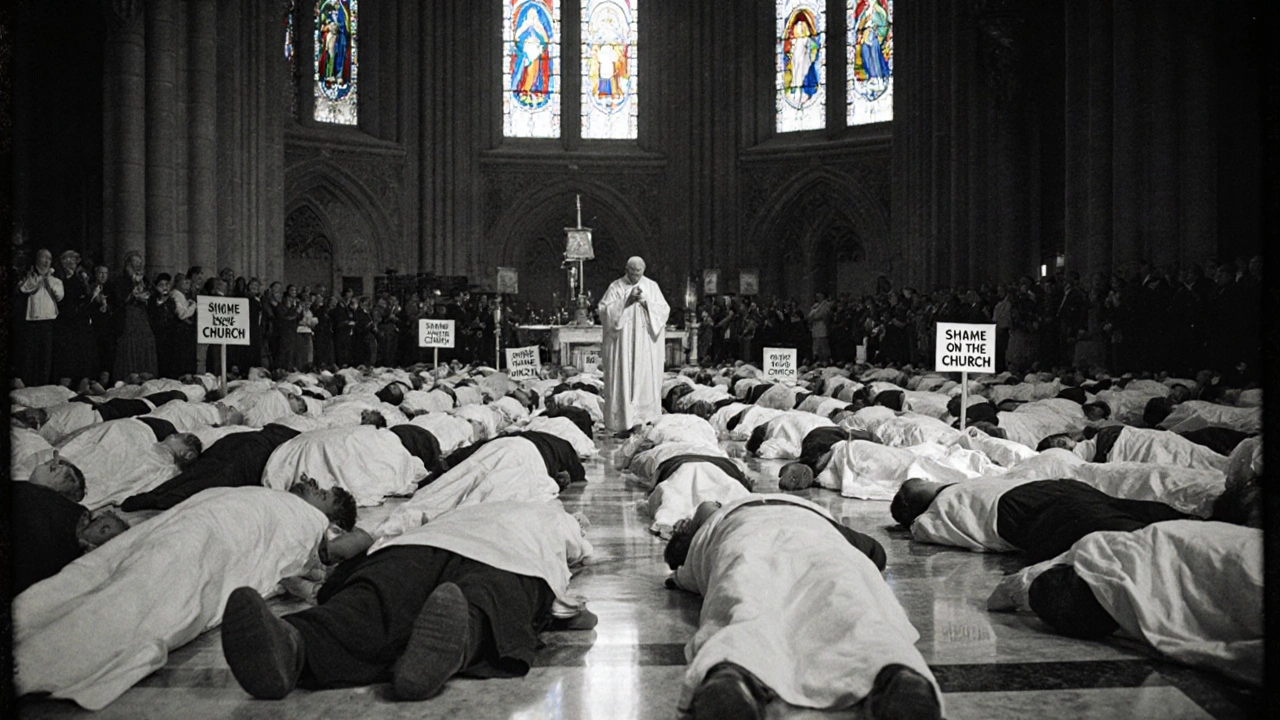

Their first big move was on Wall Street, March 24, 1987. Two hundred and fifty activists blocked traffic, chained themselves to the New York Stock Exchange, and held signs that read: "DRUG COMPANIES PROFIT FROM OUR DEATH." They weren’t just angry-they were precise. They wanted Burroughs Wellcome to lower the price of AZT. Six months later, they did. A 20% cut. It wasn’t charity. It was a win. Then came the churches. On December 10, 1989, 4,500 people marched into St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City during Mass. They lay on the floor, coughing, moaning, holding signs: "SHAME ON THE CHURCH." The Catholic Church had blocked condom education, called HIV a moral issue, and refused to fund prevention. The police arrested 111 people that day. The headlines screamed. The silence broke. And then, the FDA. On October 11, 1988, 1,600 activists surrounded the FDA headquarters in Rockville, Maryland. They carried coffins. They blocked entrances. They chanted: "SEIZE CONTROL OF THE FDA!" The agency had taken six to seven years to approve a single drug. People were dying while waiting for paperwork. Within four years, the FDA created the accelerated approval pathway. For AIDS drugs, approval time dropped to under three years. By 1995, it was down to 1.2 years. That’s not bureaucracy. That’s activism.Women, Needle Exchanges, and the White House

Men weren’t the only ones dying. But for years, women weren’t even counted. The CDC’s definition of AIDS only included symptoms that mostly affected men. So if a woman had Kaposi’s sarcoma or pneumonia-common in women with HIV-she wasn’t officially diagnosed with AIDS. That meant she couldn’t get Social Security, Medicaid, or disability. Her husband could. She couldn’t. That changed because of WHAM!-the Women’s Health Action Movement, a subgroup of ACT UP. In 1993, they forced the CDC to rewrite the definition. Suddenly, thousands of women were recognized as having AIDS. Benefits followed. Lives were saved. Needle exchanges were another battleground. In the late 80s, IV drug users were getting HIV at alarming rates. But federal law banned funding for needle programs. The Clinton administration refused to change it-even as overdose deaths climbed. In 1998, ten ACT UP activists broke into the office of Sandra Thurman, the White House’s AIDS policy coordinator. They chained themselves to her desk. They stayed for hours. Nine were arrested. Eighteen months later, the administration reversed its position. Federal funding for needle exchanges began.

From New York to South Africa

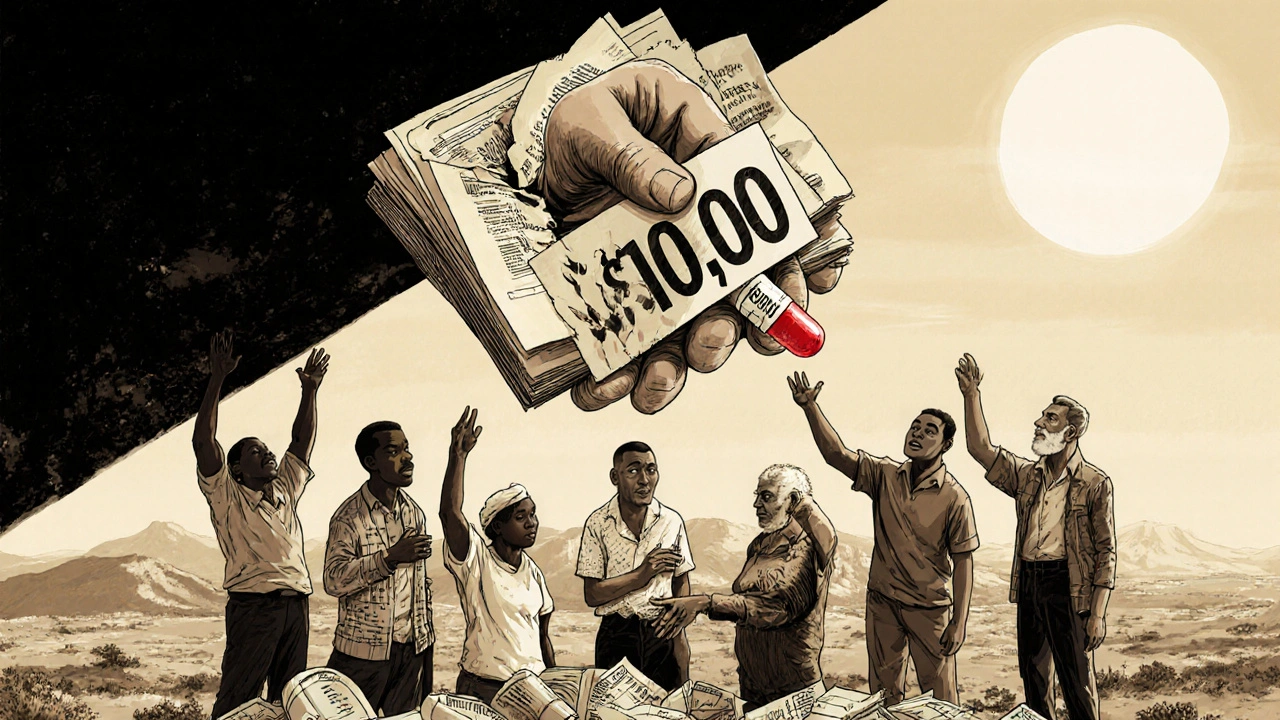

ACT UP wasn’t just a New York thing. By 1991, there were chapters in over 150 cities-from Los Angeles to Edinburgh to Cape Town. In Scotland, activists blocked traffic outside the Scottish Office. They demanded funding go to areas with the highest HIV rates. Within a year, services in those areas improved by 37%. But their biggest global win came in 1999. Pharmaceutical companies were suing South Africa for making cheap generic versions of HIV drugs. The price? $10,000 per patient per year. In a country where most people lived on less than $2 a day, that was a death sentence. ACT UP in New York and Philadelphia joined forces with South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign. They organized protests outside drug company headquarters. They flooded the media. They made it impossible to ignore. In 18 months, the companies dropped the lawsuit. Generic drugs dropped the price to $300 a year. Millions gained access. That’s not medicine. That’s justice.How They Changed Medicine Forever

ACT UP didn’t just win policy battles. They rewrote the rules of medical research. Before ACT UP, clinical trials were run by doctors and scientists-mostly men, mostly white, mostly not living with HIV. Patients were subjects. Not partners. ACT UP demanded a seat at the table. They pushed the NIH to create the first-ever Patient Advocate program in 1990. People with HIV were hired to review trial designs, suggest endpoints, and help decide who got in. They asked: "Why test a drug that takes six months to work when people are dying in six weeks?" They changed the questions. And the answers. That model didn’t stay in HIV research. Today, it’s standard for cancer, Alzheimer’s, and rare diseases. The NIH estimates that these changes saved 14 million lives globally by speeding up access to treatment.

They’re Still Here

You might think AIDS is over. It’s not. As of 2023, 9.2 million people living with HIV still can’t get treatment. In the U.S., 35 states still have laws that criminalize HIV exposure-even when there’s no risk of transmission. PrEP, the pill that prevents HIV, is still too expensive for many. Trans people of color are still being denied care. ACT UP still exists. There are active chapters in 37 cities. In New York, they’re protesting insurance denials for PrEP. In Paris, they’re demanding affordable HIV tests. In Los Angeles, they’re fighting HIV criminalization. And their tactics? They’re everywhere now. Black Lives Matter used their die-ins. The COVID-19 Treatment Action Group copied their FDA protests in 2020. When people are ignored, they don’t wait. They act.What They Taught Us

ACT UP didn’t win because they were right. They won because they were relentless. They turned grief into power. They turned silence into noise. They didn’t ask for a seat-they built their own table. Their legacy isn’t just in laws or drugs. It’s in the idea that health is a human right-and that rights aren’t given. They’re taken. The next time you hear someone say "change takes time," remember: it didn’t take time for ACT UP. It took courage. And it took action.What was ACT UP and how did it start?

ACT UP, or the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, was formed on March 12, 1987, in New York City after activist Larry Kramer gave a speech calling for direct action against government inaction during the AIDS crisis. It began with about 300 people who refused to accept the deaths of their friends and loved ones as inevitable. The group was non-partisan, grassroots, and focused on using civil disobedience to force policy changes in healthcare, pharmaceutical pricing, and public education.

How did ACT UP get drug prices lowered?

ACT UP targeted pharmaceutical companies directly. Their first major action was a protest on Wall Street against Burroughs Wellcome, which was selling AZT-the only approved AIDS drug at the time-for $10,000 a year. Activists disrupted trading, held signs, and demanded a price cut. Within six months, the company lowered the price by 20%. This set a precedent: protests could force corporations to change pricing when lives were at stake.

Why did ACT UP protest at St. Patrick’s Cathedral?

The Catholic Church publicly opposed condom use and comprehensive sex education, which were critical tools to stop HIV transmission. On December 10, 1989, over 4,500 ACT UP members entered St. Patrick’s Cathedral during Mass, lay on the floor as if dead, and held signs condemning the Church’s silence. The protest resulted in 111 arrests and forced national conversation about religion, morality, and public health.

How did ACT UP help women with HIV?

Before 1993, the CDC’s definition of AIDS only included conditions more common in men, like Kaposi’s sarcoma. Women with HIV who developed pneumonia or cervical cancer were labeled as having "AIDS-Related Complex" (ARC) and denied benefits. ACT UP’s Women’s Health Action Movement (WHAM!) campaigned relentlessly, leading the CDC to expand its definition to include women-specific symptoms. This allowed thousands of women to qualify for Social Security and medical aid.

Did ACT UP influence global health policy?

Yes. In 1999, ACT UP chapters in New York and Philadelphia joined forces with South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign to pressure pharmaceutical companies to drop a lawsuit against South Africa’s plan to produce generic HIV drugs. The companies withdrew the lawsuit, allowing generic versions to be sold for $300 a year instead of $10,000. This opened treatment to millions in low-income countries and became a model for global health justice.

Is ACT UP still active today?

Yes. As of 2023, ACT UP has active chapters in 37 cities, including New York, Los Angeles, and Paris. They now focus on expanding access to PrEP, fighting HIV criminalization laws in 35 U.S. states, and pushing for global treatment equity. Nearly 2 million people still die of AIDS each year, and activists say the fight isn’t over.

How did ACT UP change medical research?

ACT UP forced the NIH to create the first Patient Advocate program in 1990, giving people living with HIV direct roles in designing clinical trials. They insisted that research questions reflect real needs-not just scientific curiosity. This model of community involvement became standard in cancer, Alzheimer’s, and rare disease research. The NIH credits this shift with saving an estimated 14 million lives globally through faster drug access.