Justice Disparity Calculator

The justice system in Jim Crow Alabama was designed to protect white men and punish Black people. Between 1880 and 1951, only 12 white men were executed for raping Black women in the South. Meanwhile, 455 Black men were executed for allegedly raping white women—many based on nothing but accusation.

This calculator shows the historical disparity. The system didn't fail to deliver justice—it was deliberately constructed to deny Black women justice while punishing Black men.

The Disparity

Black men were executed 37.9 times more frequently than white men for similar alleged crimes.

Why This Happened

The legal system was built on white supremacy. Rape of Black women was often ignored while allegations against Black men were treated as fact.

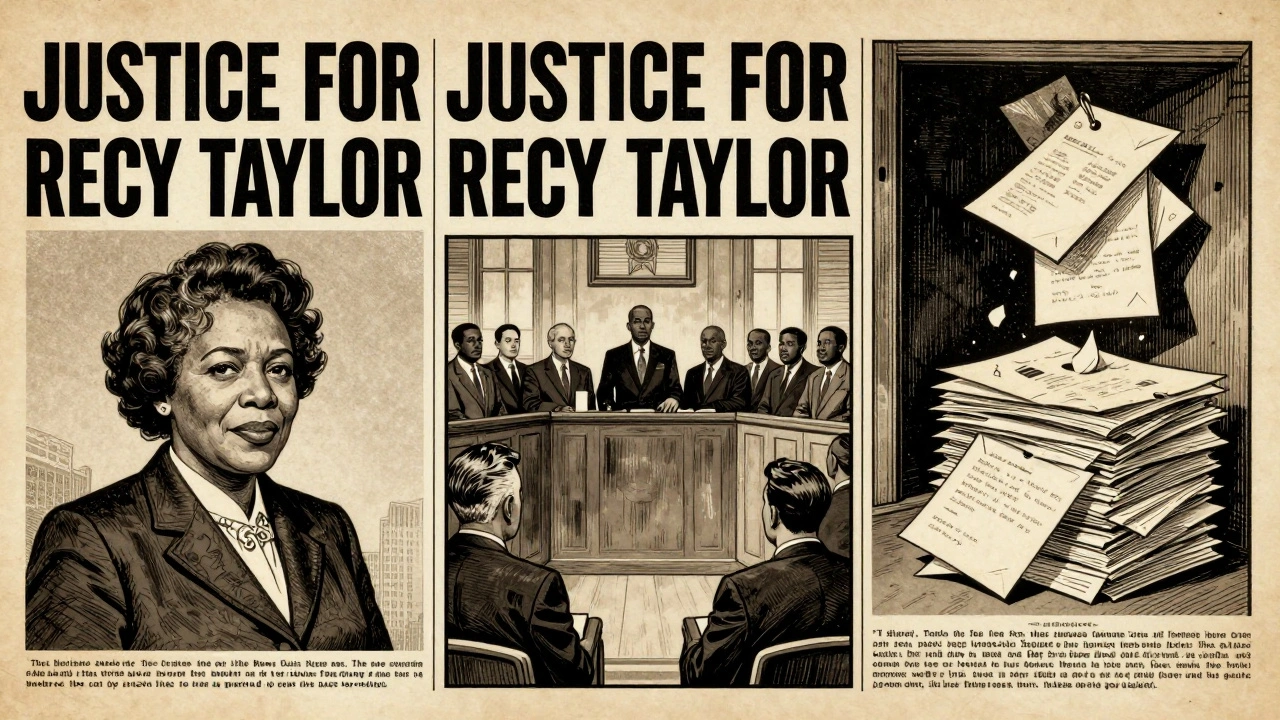

Recy Taylor was assaulted by seven white men. The justice system failed her completely.

Alabama finally passed an apology for failing to prosecute Taylor's attackers.

The Legacy

Today, Black women are still 2.5 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than white women. They're less likely to be believed and less likely to see their attackers prosecuted.

Recy Taylor's story shows that justice doesn't come from courts alone—it comes from people who demand it. Her case was the first organized campaign to challenge sexual violence as a civil rights issue.

This historical disparity reminds us that the system wasn't broken—it was designed this way. And the patterns continue to this day.

On a dark night in September 1944, Recy Taylor, a 24-year-old Black mother and sharecropper, was walking home from church in Abbeville, Alabama, when seven armed white men pulled her into a car at gunpoint. They drove her to a secluded stretch of woods, took turns raping her, and then left her blindfolded on the side of the road. She didn’t scream. She didn’t fight back. She knew what would happen if she did. This wasn’t an isolated incident-it was the norm. But Recy Taylor did something no one expected: she told the truth.

The System Was Designed to Fail Her

The local sheriff, Howell L. Gramble, didn’t even try to arrest the men. When Taylor identified them by name, he dismissed her claims. He called her a "whore." He said she had venereal disease. He claimed he’d already investigated and arrested everyone involved-even though no one had been arrested. No lineup. No evidence collection. No follow-up. The men who raped her were known to him. One was a U.S. Army private. Another was the son of a local landowner. The system wasn’t broken-it was working exactly as intended.Two grand juries, both made up of all-white, all-male citizens, heard the case. The first met for five minutes and refused to indict. The second, convened after national pressure mounted, heard the same evidence-and again said no. Four of the seven attackers admitted to having sex with Taylor. But they claimed she was a willing participant. One man, Joe Culpepper, later gave a detailed confession that matched Taylor’s account: they kidnapped her, threatened her with guns, and raped her in sequence. None of it mattered.

Rosa Parks Didn’t Wait for Permission

Within days, the NAACP sent Rosa Parks to Abbeville. She wasn’t just an organizer-she was a veteran of fighting sexual violence against Black women. She’d spent years documenting cases like Taylor’s, trying to get justice where none existed. Parks didn’t go to Abbeville to comfort Taylor. She went to build a movement.She started the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor. Within weeks, it became the most powerful campaign of its kind in a decade. Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier ran 27 major stories on the case. Letters poured into Alabama’s governor’s office-over 10,000 of them-from churches, unions, and women’s groups across the country. Even Eleanor Roosevelt spoke out. For the first time, the rape of a Black woman became a national scandal.

But the backlash was swift. Taylor’s home was firebombed in December 1944. Death threats followed her everywhere. She and her family were forced to flee Alabama. The state offered no protection. The same men who attacked her walked free. The justice system didn’t just fail her-it punished her for speaking up.

Why This Case Changed Everything

This wasn’t just about one woman. It was about a pattern. Between 1880 and 1951, only 12 white men were executed for raping Black women in the entire South. Meanwhile, 455 Black men were executed for allegedly raping white women-many based on nothing but accusation. The law didn’t protect Black women. It weaponized their bodies to uphold white supremacy.The Taylor case was different because it was organized. It didn’t rely on pity. It didn’t ask for mercy. It demanded accountability. The Committee for Equal Justice didn’t just focus on Taylor. They began documenting every case of sexual violence against Black women in Alabama. They turned individual trauma into collective resistance. That strategy became the blueprint for the Montgomery Bus Boycott a decade later.

Rosa Parks didn’t suddenly decide to refuse to give up her seat in 1955. She’d been doing this work for years. She’d fought for Jeremiah Reeves, a Black teenager falsely accused of raping a white woman. She’d built networks of Black women who shared stories, collected affidavits, and kept pressure on officials. The bus boycott didn’t come out of nowhere. It was the next step in a campaign that began with Recy Taylor.

The Silence That Lasted Decades

For over 60 years, Recy Taylor’s story was buried. Textbooks skipped it. Movies ignored it. Even in civil rights histories, she was a footnote-if mentioned at all. The mainstream narrative preferred to focus on marches and speeches, not the quiet, brutal violence that shaped Black women’s lives every day.But the truth doesn’t stay buried forever. In 2011, 67 years after the assault, the Alabama Legislature passed a formal apology. House Resolution 6 acknowledged the state’s failure to prosecute her attackers. It called her an "American hero." It admitted the judicial system had betrayed her. The apology came when Taylor was 91. She never saw justice. But she lived long enough to see the state admit it had lied.

Her story didn’t end there. In 2017, the documentary The Rape of Recy Taylor brought her name to a new generation. When she died at 97 later that year, The New York Times and The Washington Post ran front-page obituaries. For the first time, millions of people learned who she was-not as a victim, but as a woman who refused to be erased.

What This Case Teaches Us Today

Recy Taylor’s story isn’t history. It’s a mirror. Today, Black women are still 2.5 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They’re still less likely to be believed. Still less likely to see their attackers prosecuted. The names change-Tarana Burke, Breonna Taylor, Tamika Palmer-but the pattern doesn’t.The lesson from Recy Taylor isn’t that justice failed. It’s that justice doesn’t come from courts. It comes from people. From the women who gather in churches and living rooms to share stories. From the journalists who refuse to look away. From the organizers who turn grief into action. Rosa Parks didn’t wait for permission to act. She didn’t wait for the system to change. She built a new one.

Recy Taylor spoke up when silence was safer. She didn’t get a conviction. But she got something more powerful: a movement. And that movement didn’t die. It just passed the torch.

Why wasn’t Recy Taylor’s case ever prosecuted?

The case was never prosecuted because the legal system in Jim Crow Alabama was designed to protect white men, not Black women. Two all-white, all-male grand juries refused to indict the attackers, despite multiple confessions and Taylor’s clear identification of the men. The sheriff dismissed her claims, made false statements about the investigation, and failed to even conduct a lineup. The state had no interest in punishing white men for assaulting Black women-it had every interest in maintaining racial hierarchy.

How did Rosa Parks get involved in Recy Taylor’s case?

Rosa Parks was the secretary of the NAACP’s Montgomery chapter and had spent years investigating sexual violence against Black women. When news of Taylor’s assault reached the NAACP, Parks was immediately dispatched to Abbeville to gather testimony and organize support. Her work on this case laid the foundation for her later activism, including her role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. She used the same strategies-documenting stories, mobilizing media, pressuring officials-that she would later apply to fight segregation on buses.

What impact did the Black press have on the Recy Taylor case?

The Black press turned a local crime into a national movement. Newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier published 27 major articles on the case between September 1944 and March 1945. They gave Taylor a voice, exposed the corruption in Alabama’s justice system, and connected her case to a broader pattern of sexual violence. This coverage pressured the governor to appoint a special prosecutor and generated over 10,000 letters demanding justice. Without the Black press, the case would have vanished.

Why is Recy Taylor considered a catalyst for the civil rights movement?

Recy Taylor’s case was the first large-scale, organized campaign to challenge sexual violence as a civil rights issue. The Committee for Equal Justice built a national coalition across race and class lines, used media strategically, and forced political leaders to respond. These tactics became the model for future movements, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Historians now recognize that Parks’ activism didn’t begin with the bus-it began with Taylor.

Did the state ever offer any form of justice to Recy Taylor?

Yes-but only after 67 years. In 2011, the Alabama Legislature passed House Resolution 6, formally apologizing to Recy Taylor for the state’s failure to prosecute her attackers. The resolution acknowledged the two grand juries’ refusal to act despite credible evidence and called her an "American hero." No one was ever punished, but the apology was the first official recognition that the system had committed a grave injustice.