Consent Scenario Simulator

A classmate asks to borrow your drawing, but you're not finished. They keep asking even after you say "No, I'm not done." What do you say?

Why Consent Education Starts in Kindergarten

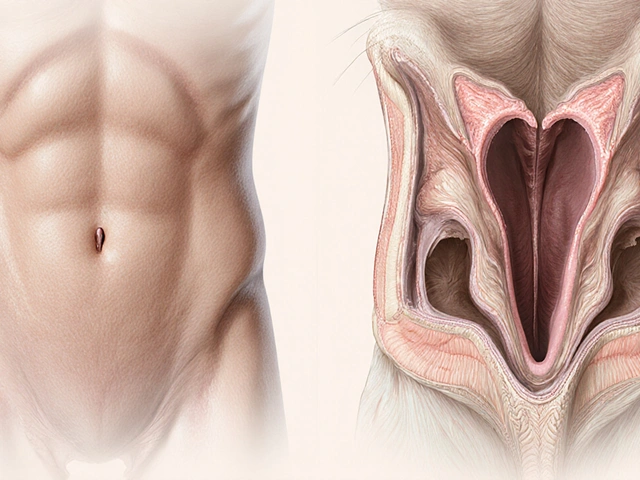

Most people think consent is about sex. But it starts long before that-with a child saying no to a hug, or a teacher asking if it’s okay to help tie their shoe. Consent isn’t a topic for high school health class. It’s a daily skill, learned early and reinforced often. In schools across California, Oregon, and New Jersey, kids as young as five are learning that their body belongs to them. No one gets to touch them without permission-not even a relative, not even a teacher. That’s not radical. It’s basic.

By third grade, students are naming their personal space. By sixth grade, they’re talking about what happens when someone says ‘maybe’ or stays quiet. By ninth grade, they’re mapping out how alcohol, power, or fear can make consent impossible. This isn’t theory. It’s practice. And it’s working. In districts that fully implemented Oregon’s K-12 consent standards, reports of boundary violations in middle school dropped by 19% in just two years.

What Consent Actually Means-Beyond ‘No’

Too many people think consent is just about saying no. But real consent is about saying yes-and knowing how to say it clearly. The California Healthy Youth Act defines it as ‘an ongoing affirmative communication that demonstrates a conscious and voluntary agreement.’ That means consent isn’t a one-time nod. It’s a conversation. It can be taken back. It needs to be free of pressure.

Imagine a student who’s been told to ‘be nice’ to a classmate who keeps invading their space. That student learns to say, ‘I don’t like that,’ but gets scolded for being ‘rude.’ Now imagine the same student, taught that their comfort matters, and given phrases like, ‘I need space right now,’ or ‘Can we talk about this later?’ That student isn’t just learning boundaries-they’re learning agency. And that changes everything.

SafeBAE’s curriculum, used in over 300 schools, teaches consent as part of healthy relationships-not as a warning label. Students practice scenarios: What if someone says yes but looks scared? What if they’re laughing nervously? What if they’re too tired to say anything? These aren’t hypotheticals. They’re real moments that happen in locker rooms, at parties, in group chats.

How Schools Are Building Communication Skills

Consent education isn’t just about what to say. It’s about how to listen. Schools that do this well teach active listening as part of the curriculum. Students learn to read body language-not as a skill to ‘catch lies,’ but to recognize discomfort. A crossed arm. Averted eyes. A forced smile. These aren’t secrets. They’re signals.

In Washington state, eighth graders analyze how power affects consent. Who has more influence in the room? The popular kid? The coach? The teacher? The older sibling? Students learn that consent can’t exist when someone fears consequences. If you say yes because you’re scared of being left out, that’s not consent. That’s coercion.

Teachers use role-playing, not lectures. One exercise: Two students stand back-to-back. One says, ‘I want to hug you.’ The other can say yes, no, or ask for time. Then they switch. No judgment. No correction. Just practice. Over and over. By the time students are 16, they’ve had dozens of these conversations in safe spaces. That’s why schools in Maryland report students are 40% more likely to speak up about discomfort by eighth grade.

Why This Isn’t Just a Health Class Issue

Consent doesn’t live in the health classroom. It lives in the hallway, the cafeteria, the group project, the text thread. That’s why the best programs spread it across subjects. In English class, students read stories where characters misread signals. In art, they design posters about personal space. In history, they examine how gender norms have shaped who gets to say no.

A 2021 Stanford pilot study found that when consent was taught only in health class, students remembered 58% of the material after six weeks. When it was woven into English, social studies, and even math (through data analysis of survey results on peer behavior), retention jumped to 85%. That’s not magic. It’s repetition in context.

One teacher in Chicago had students write letters to their future selves: ‘What do you want people to know about your boundaries?’ Another in Philadelphia led a debate: ‘Should a teacher be allowed to hug a student, even if the student says yes?’ These aren’t distractions. They’re deepening understanding.

The Real Barriers-Teachers, Politics, and Fear

Here’s the truth: Most teachers want to teach this. But they don’t feel ready. A 2020 survey found only 38% of health educators felt ‘very prepared’ to lead consent lessons. Why? Because they were never trained. No one showed them how to handle a student crying after a role-play. No one gave them scripts for when a parent says, ‘This isn’t what I sent my kid to school for.’

That’s why organizations like SafeBAE now offer full lesson kits-slide decks, videos, printable worksheets, even scripts for parent meetings. They’ve made it easy. But the bigger problem is politics. In 2022, 37% of school districts in conservative states canceled or softened consent lessons because of pressure. In liberal districts, that number was 8%.

Some parents worry this teaches kids to be sexual. It doesn’t. It teaches them to be safe. It teaches them that silence isn’t consent. That pressure isn’t love. That their body isn’t a gift to give. It’s their own.

What Works-And What Doesn’t

Not all consent education is equal. Programs that focus only on ‘say no’ or ‘don’t get drunk’ fail. Why? Because they treat students like victims, not agents. The best programs do three things:

- Start early-before puberty, before dating, before social pressure kicks in.

- Use consistent language-‘yes means yes,’ ‘no means no,’ ‘maybe means no,’ ‘silence means no’-across all grades.

- Include everyone-boys, girls, nonbinary students, LGBTQ+ youth. Consent isn’t a girl’s issue. It’s a human one.

California’s model is the gold standard. It requires materials to be inclusive of all sexual orientations and gender identities. It bans shame. It doesn’t say, ‘Don’t have sex.’ It says, ‘If you do, make sure it’s wanted.’

Meanwhile, states that wait until high school or college? They’re too late. Research shows students who get consent education before age 12 are 30% less likely to experience sexual violence by age 18. That’s not a guess. That’s data from Harvard and the CDC.

What Comes Next

Seven states introduced consent education bills in 2023 and 2024. But full national adoption? Experts say it won’t happen until 2030-2035. Why? Because change moves slowly when fear drives policy.

But it’s moving. More schools are training teachers. More districts are adopting SafeBAE or similar programs. More parents are asking, ‘What are they teaching my kid?’ And when they hear the answer-‘They’re learning how to respect themselves and others’-they stop pushing back.

The goal isn’t to create perfect students. It’s to create people who know their worth, who listen to others, and who don’t need a law to tell them when something’s wrong.

How You Can Support Consent Education

If you’re a parent: Ask your school what they teach about boundaries and consent. Don’t assume it’s covered. Ask for the curriculum. Ask if it includes younger grades. Ask if it’s inclusive.

If you’re a teacher: You don’t need to be an expert. Use free resources from SafeBAE or the California Department of Education. Start small-one lesson, one conversation. You don’t need to fix everything. Just begin.

If you’re a student: Speak up. If your school doesn’t teach this, say so. Write a letter. Start a club. You’re not too young to demand better.

Consent isn’t a lesson. It’s a practice. And it starts the moment a child learns their voice matters.