Historical Erasure Impact Calculator

How Historical Erasure Affects Different Communities

Based on the article "Female-Female Sex in the Archives: Why Lesbianism Was Erased from History," this calculator estimates how likely documentation from different groups would have been preserved in historical archives.

Enter your selections to see how your documentation would have been preserved

Why This Matters

As the article explains, 83% of women in Oregon lost personal documents due to fear. Only 12% of major research libraries worldwide have specific lesbian subject headings, dropping to 4% for women of color.

For most of the 20th century, if you looked for records of women loving women in official archives, you wouldn’t find them. Not because they didn’t exist - but because someone made sure they were hidden. Lesbianism wasn’t just ignored; it was actively erased from paper, catalogs, and public memory. The silence wasn’t accidental. It was policy.

The Archives Didn’t Just Miss Lesbianism - They Deleted It

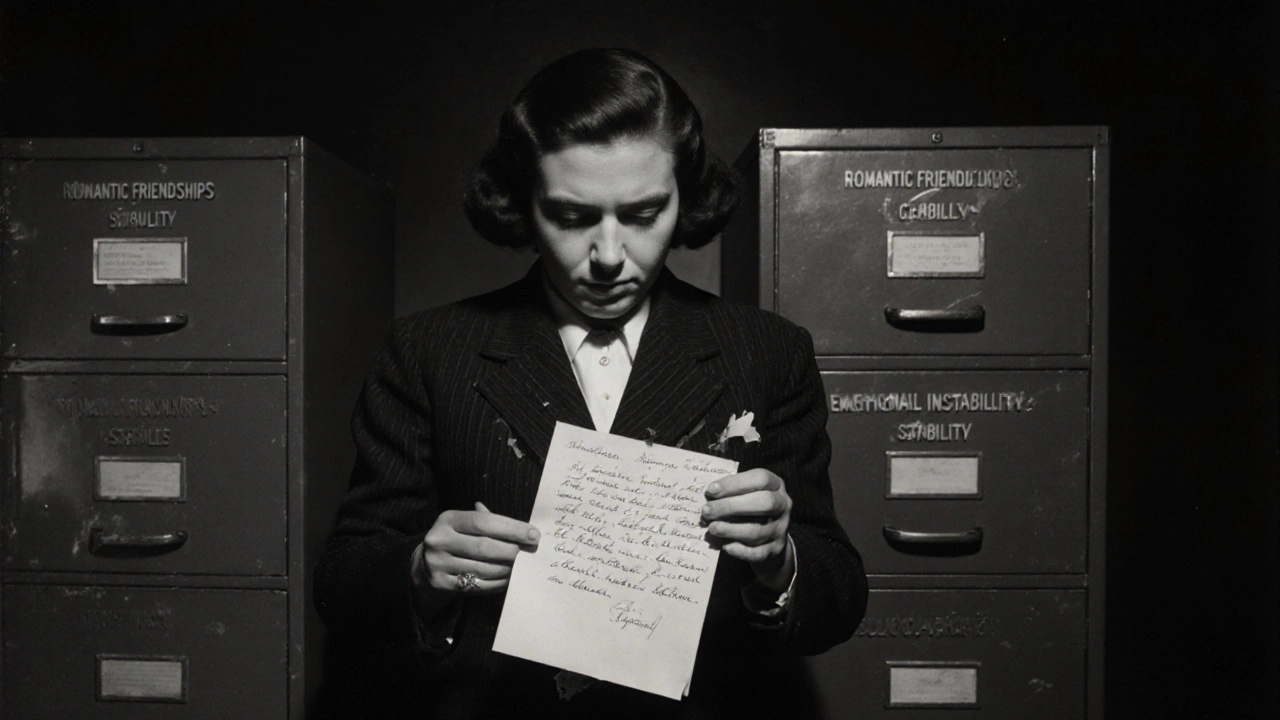

Libraries and government institutions didn’t fail to collect lesbian materials. They chose not to. In the 1950s and 60s, archivists followed strict guidelines that labeled anything hinting at same-sex relationships as "indecent," "deviant," or "morally questionable." Materials were thrown out, locked away, or recategorized under vague terms like "romantic friendships" or "Boston marriages." These weren’t neutral descriptions - they were code. They let institutions pretend they were preserving history while quietly scrubbing out the sexual reality of women’s lives. The Library of Congress didn’t even have a subject heading for "Lesbians" until 1972. Before that, if you searched for anything related to women who loved women, you got nothing. Or worse - you got misclassified material. A letter between two women sharing a home might be filed under "domestic life," while a diary describing a kiss was labeled "emotional instability." The system wasn’t broken. It was working exactly as designed.Why Was Female-Female Sex So Hard to Name?

There’s a myth that lesbianism was invisible because women didn’t have sex with each other. That’s false. The truth is, it was too visible - and too dangerous. In the U.S., 49 states had sodomy laws that technically applied to women, even though they were rarely enforced against them. That didn’t make it safer. It made it riskier. Police could still use those laws to justify raids, arrests, or harassment. Employers fired women for suspected lesbianism. Families disowned them. Churches condemned them. So women learned to hide. They wrote love letters in code. They used pseudonyms in magazines. They whispered in basements. The first lesbian publication in the U.S., The Ladder, launched in 1956, avoided the word "lesbian" in its early issues. It didn’t want to get banned by the U.S. Postal Service, which considered any mention of homosexuality "obscene." Instead, it used phrases like "the love that dare not speak its name" - a phrase borrowed from Oscar Wilde, ironically, to describe male homosexuality. Even when women did write openly, their words were often destroyed. A 2018 oral history project in Eugene, Oregon, found that 83% of women interviewed had lost letters, photos, or diaries because a parent, partner, or roommate destroyed them out of shame or fear. One woman recalled burning her journal after her mother found it. "I didn’t want her to go to jail," she said. "I didn’t know if she could be arrested for reading it."When the Silence Broke: The Rise of Radical Archives

The first real crack in the wall came in the early 1970s. A group of lesbian activists in New York realized something terrifying: their history was disappearing faster than it was being made. They didn’t wait for universities or governments to act. They started collecting everything themselves. The Lesbian Herstory Archives was born in a Brooklyn apartment. Volunteers gathered photographs, buttons, newsletters, personal letters, and even quilts stitched by women who had lived together for decades. They didn’t use library cataloging rules. They didn’t care about "objectivity." They cared about truth. If a woman wrote, "I love her," they kept it. If a woman said, "We had sex every night," they kept it. They didn’t sanitize. They didn’t euphemize. By 2023, the archive held over 400 collections - more than any university library in the country. Their Periodicals Collection alone included over 1,500 lesbian magazines and newsletters, many of which had never been seen outside of private homes. One issue of The Ladder from 1957 had a single line: "We are not sick. We are not perverts. We are women." That line was printed on a page that had been folded and hidden inside a book for 40 years before someone donated it. Similar efforts popped up across the country. The June Mazer Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles started with a shoebox of photos. The ONE Archives in USC began as a collection of gay men’s magazines - but women soon began donating their own materials, forcing the archive to expand its scope. These weren’t just storage spaces. They were acts of rebellion.

The Hidden Layers: Class, Race, and Who Got Left Out

Even within these radical archives, the story isn’t complete. The women who had the means to write letters, keep diaries, or attend meetings were often white, middle-class, and educated. Working-class lesbians, Black lesbians, Indigenous lesbians, and immigrant lesbians had fewer resources to document their lives. Their stories were lost not just to silence - but to poverty. A 2021 study by the International Federation of Library Associations found that only 12% of major research libraries worldwide have dedicated subject headings for lesbian sexuality. That number drops to 4% for archives that include materials from women of color. The Lesbian Herstory Archives admits it still struggles to collect materials from trans women and nonbinary people who were historically misclassified as "lesbians" - a reflection of how early LGBTQ+ movements often ignored gender diversity. One oral history from Sonoma County, California, tells of a Black woman in the 1960s who worked as a domestic worker. She never wrote anything down. She didn’t trust the system. But she kept a small wooden box under her bed. Inside: a single photo of her and her partner, taken at a picnic in 1963. They’re smiling. They’re holding hands. The photo was found after her death. No one else knew they were together.What’s Still Missing - And Why It Matters Today

Even now, with digital archives and online databases, the erasure isn’t over. Many archives still use outdated cataloging systems. A letter from a woman to her partner might be tagged as "correspondence" or "personal papers," not "lesbian love letter." Search engines can’t find what isn’t labeled. And if you don’t know what to search for, you’ll never find it. The 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade reignited fears about digital surveillance. If your phone, email, or browser history could be used against you, what happens to old love letters, text messages, or social media posts? The same systems that erased lesbian history are still in place - now just digital. That’s why the work of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, the Digital Transgender Archive, and others matters more than ever. They don’t just preserve documents. They restore dignity. They say: Your love was real. Your life mattered. We saw you. We remember you.

What You Can Do to Help Keep the Memory Alive

If you have letters, photos, or journals from women who loved women - keep them. Don’t throw them out. Don’t hide them. Scan them. Write down the names, dates, and stories. Even if you think it’s "just personal," it’s not. It’s history. Support community archives. Donate to the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Volunteer at a local LGBTQ+ historical society. Ask your local library if they have a dedicated LGBTQ+ collection - and if they don’t, ask why. And if you’re a student, researcher, or archivist: challenge the cataloging rules. Demand better subject headings. Push back against euphemisms. Name the thing. Say "lesbian." Say "sex." Say "love." Because silence isn’t neutrality. Silence is complicity.What’s Next

The next generation of archivists is building new systems - ones where people can describe their own lives in their own words. The Digital Transgender Archive now lets users choose their own labels instead of forcing them into outdated categories. Community archives across Canada and the U.S. are sharing metadata so that a letter from a woman in Michigan can be found by someone in Toronto. It’s slow work. But it’s working. The buttons at the Lesbian Herstory Archives tell the story: early ones said, "I am your worst fear." Today, they say, "Lesbian." Simple. Clear. Unapologetic. That’s the goal now: to make sure no one ever has to wonder again whether their love was real - because the archives will say it was.Why weren’t lesbian relationships documented in historical archives?

Lesbian relationships were rarely documented because institutions actively suppressed them. Archivists, librarians, and government agencies used policies that labeled same-sex relationships as "indecent," "deviant," or "obscene." Library catalogs lacked proper subject headings - the Library of Congress didn’t include "Lesbians" until 1972. Materials were destroyed, misfiled under vague terms like "romantic friendships," or ignored entirely to avoid controversy and legal risk.

What is the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and why was it created?

The Lesbian Herstory Archives, founded in 1974 in Brooklyn, was created by lesbian activists who realized that lesbian history was being erased. Unlike traditional archives, it collects personal materials - letters, photos, diaries, buttons, and magazines - without sanitizing them. It deliberately rejects institutional censorship and preserves the raw, unfiltered truth of lesbian lives, making it the largest collection of lesbian materials in the world.

How did early lesbian publications like The Ladder avoid censorship?

The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in the U.S. (1956-1972), avoided explicit sexual language to escape postal censorship. Early issues used coded phrases like "the love that dare not speak its name" and focused on identity, community, and legal rights instead of sexual acts. Even so, the magazine was still at risk of being banned - its editors walked a tightrope between visibility and survival.

Why are working-class and women of color underrepresented in lesbian archives?

Working-class lesbians and women of color often lacked the resources, education, or safety to keep written records. Many couldn’t afford to buy paper, mail letters, or attend meetings. Others feared that even possessing documents could lead to job loss, eviction, or arrest. As a result, their stories survived mostly through oral tradition - making them harder to preserve in traditional archives that prioritize written materials.

Is lesbian erasure still a problem today?

Yes. Only 12% of major research libraries worldwide have specific subject headings for lesbian sexuality. Many digital archives still use outdated, vague tags like "same-sex relationships" instead of "lesbian." Search algorithms can’t find what isn’t labeled. And with rising digital surveillance, preserving private records - like texts or emails - has become even more urgent and risky.

How can individuals help preserve lesbian history?

Keep personal documents - letters, photos, journals - and scan them. Share them with community archives like the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Ask libraries to add proper LGBTQ+ subject headings. Support organizations that collect oral histories. And most importantly: name the truth. Say "lesbian." Say "sex." Say "love." Silence helps erase. Voice helps preserve.