When people talk about abortion in the U.S. today, they often reach back to history to justify their position. One name that keeps popping up is Henry de Bracton a 13th-century English jurist whose legal treatise shaped centuries of English common law. But what did he actually say about abortion? And how is it being used-or misused-in modern courtrooms?

Bracton wrote De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae around 1235. It wasn’t a law passed by Parliament. It was a scholar’s attempt to organize what judges were already doing. He didn’t invent rules-he recorded them. And when it came to abortion, he made a clear distinction: before quickening and after quickening.

Quickening meant the moment a pregnant woman first felt the fetus move. In Bracton’s time, that usually happened between 18 and 25 weeks. Before that? The fetus wasn’t considered alive in the legal sense. He wrote that if someone gave a woman poison to end a pregnancy before quickening, it was a misdemeanor-a misprision. But if the fetus was already moving, and someone killed it, that was homicide. The penalty? Death.

But here’s the twist: Bracton wasn’t the only voice. His book was one of many. Another medieval text, Britton, written around the same time, said something completely different: "For an infant killed within her womb, she may not bring any appeal... no one being bound to answer an appeal of felony." In other words, the law didn’t even treat it as a crime worth prosecuting. The Mirror of Justices, also from the 1200s, flat-out rejected the idea that abortion was homicide at any stage.

So why does Bracton get all the attention today? Because he’s the one who used the word "homicide." That’s the word modern opponents of abortion want to point to. But ignoring the other texts? That’s not history. That’s cherry-picking.

Quickening Wasn’t About Fetal Rights-It Was About Theology

Bracton didn’t come up with quickening out of thin air. He got it from church teachings. The idea that a soul entered the body at a certain point came from Aristotle, filtered through medieval theologians like Gratian. Back then, people believed a male fetus became animated at 40 days, a female one at 80 to 90. That’s why penitentials-church guides for confessing sins-gave different punishments depending on how far along the pregnancy was.

But these weren’t criminal penalties. They were spiritual ones. A poor woman who aborted because she couldn’t feed another child might get a year of fasting. A noblewoman who hid an affair might get seven years of penance. The punishment wasn’t about the fetus. It was about sex, shame, and social order.

Legal historian James Brundage showed this clearly: medieval canon law treated abortion as a sin tied to fornication, not as a crime against a person. The real offense wasn’t killing a baby-it was having sex outside marriage and then trying to cover it up.

Abortion Was a Crime Against Husbands, Not Fetuses

There’s another layer most people miss. In medieval England, women didn’t own property. Their children were their husband’s heirs. If a woman ended a pregnancy, especially if she was married, she might be seen as stealing her husband’s future inheritance. That’s why some scholars say abortion was treated as a crime against men-not the unborn.

Think about it: if a woman was accused of abortion, the case often came up because her husband claimed she’d tried to prevent him from having a legitimate son. It wasn’t about protecting life. It was about protecting lineage.

This isn’t just theory. The Cambridge University Press analysis from 2017 found that medieval laws around abortion were part of a broader system designed to control women’s bodies to ensure male heirs. The law didn’t care if the fetus was alive. It cared if the husband got his son.

What About the Mother’s Life?

Here’s something you won’t hear in modern political debates: medieval law allowed doctors to kill a fetus to save the mother.

Embryotomy-cutting up the baby inside the womb to pull it out piece by piece-wasn’t seen as murder. It was seen as a necessary evil. If the mother was dying in childbirth, and the baby was still alive inside, the law didn’t force her to die to save the fetus. The mother’s life came first.

That’s not a modern idea. That’s medieval. Canon lawyer Ivo of Chartres, writing in the 11th century, said mercy should guide judgment. And in practice, women who needed this procedure were rarely punished.

Compare that to today. Some modern laws say a woman can’t get an abortion even if her life is at risk unless the fetus is already dead. That’s not history. That’s a reversal.

Bracton Didn’t Last-Blackstone Fixed It

Bracton’s view lasted for centuries. Judges in the 1500s and 1600s still quoted him. But by the 1700s, even his biggest fans started to question him.

William Blackstone, the most influential legal scholar of the 18th century, wrote in his Commentaries on the Laws of England that killing a fetus before birth could never be murder. Why? Because the victim hadn’t been born yet. You can’t murder someone who isn’t a person under the law.

Blackstone called it a "heinous misdemeanour," not homicide. He was correcting Bracton, not following him. And Blackstone was the law for America’s founders. Thomas Jefferson read him. So did John Adams.

So when modern courts cite Bracton as proof that abortion was always illegal, they’re ignoring the very legal tradition that shaped the U.S. Constitution.

The Real Law Didn’t Change Until 1803

England didn’t make abortion a criminal offense until 1803, with Lord Ellenborough’s Act. Before that, it was mostly handled by the church. Even then, the law didn’t ban abortion outright. It only punished abortions after quickening with death. Before that? Transportation to Australia.

The U.S. didn’t criminalize abortion nationwide until the 1860s. And even then, most states allowed it before quickening. The idea that abortion was always banned? That’s a myth invented in the 1970s to push a political agenda.

Modern historians-15 of them, all published in peer-reviewed journals since 2022-have made this clear. The American Historical Association filed a brief in the Dobbs case showing that medieval law didn’t treat abortion as a crime against life. It treated it as a sin against sex, a crime against inheritance, and sometimes, a medical necessity.

Why This Matters Today

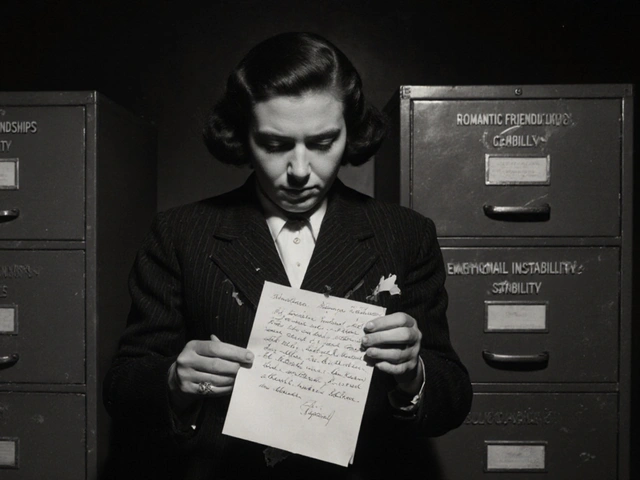

Justice Alito’s draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization cited Bracton as proof that abortion was historically criminalized. But he didn’t mention Britton. He didn’t mention Blackstone. He didn’t mention embryotomy. He didn’t mention that the law focused on husbands, not fetuses.

That’s not history. That’s propaganda.

Today, 87% of U.S. state abortion laws are built on the idea of fetal personhood-the belief that life begins at conception. But that idea didn’t exist in medieval England. It was invented in the 1970s by religious activists. Bracton’s quickening? That was about movement, not soul. About biology, not theology.

History doesn’t give us easy answers. It gives us complexity. And if we want to make real law, we need to face that complexity-not pick the parts that sound convenient.