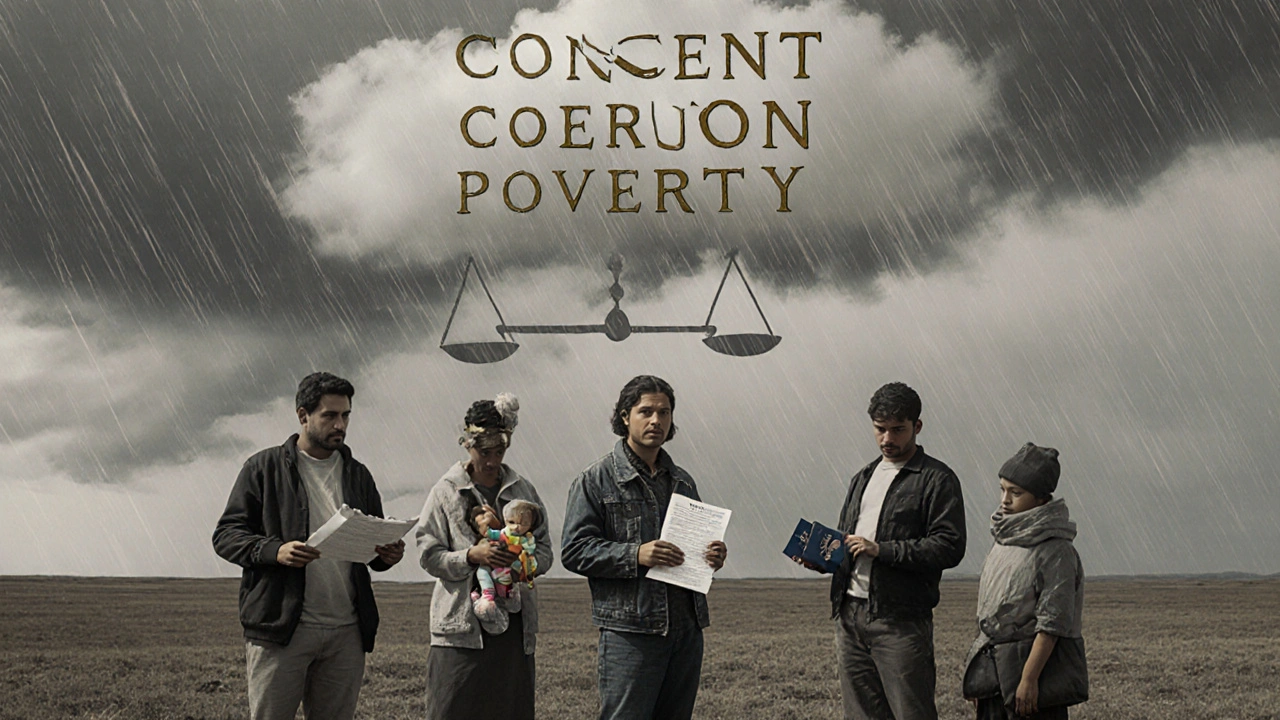

Consent Spectrum Calculator

This calculator helps you understand how various contextual factors influence consent in migration situations. The Palermo Protocol defines trafficking as involving force, fraud, or coercion where consent is irrelevant. However, in reality, consent exists on a spectrum shaped by circumstances like poverty, options, and deception.

Adjust Factors Affecting Consent

Move sliders to see how different circumstances impact the spectrum of consent

Consent Spectrum Analysis

Visual representation of how factors impact consent

Every year, thousands of people cross borders hoping for a better life. Some are helped by smugglers who charge a fee. Others are lured by fake job offers, trapped in debt, or forced into labor or sex work. But here’s the problem: the law doesn’t always see the difference between them. And that’s where things get messy.

The Legal Line That Doesn’t Match Reality

The United Nations’ Palermo Protocol, adopted in 2000, tries to draw a clear line between human trafficking and migrant smuggling. Trafficking, it says, happens when someone is moved through force, fraud, or coercion - and consent doesn’t matter. Smuggling, on the other hand, is when someone willingly pays to cross a border illegally. Simple, right? Not even close. In practice, consent isn’t a switch you flip - it’s a slow fade. A woman in rural Moldova sees an ad for a waitressing job in Italy. She calls. She’s interviewed. She signs a contract. She leaves with her documents. No one points a gun at her. No one threatens her family. But she’s desperate. Her husband lost his job. Her kids are hungry. She knows the pay will be low, but it’s better than nothing. When she gets to Italy, she’s told the job doesn’t exist. She’s forced into prostitution. She’s told she owes $15,000 for her trip. According to the law, she’s a trafficking victim. But did she consent? She did - to the job, to the trip, to the risk. She just didn’t consent to being trapped. That’s the gap. The law says consent is irrelevant if coercion follows. But what if the coercion was already there - in the poverty, in the lack of options, in the fact that every door but one was locked?Children Don’t Consent. Adults Just Think They Do

The Palermo Protocol makes a special rule for kids under 18: no matter what, if they’re moved for exploitation, it’s trafficking. Consent doesn’t count. That’s fair. A 15-year-old can’t legally consent to sex work or factory labor. But what about a 22-year-old woman from Guatemala who agrees to go to Arizona with a man she met online? He promises marriage. He gives her a plane ticket. She believes him. When she arrives, he takes her documents, locks her in an apartment, and forces her to work on the streets. She didn’t consent to that. But she did consent to the trip. She did consent to the relationship. The law says her consent to the journey is meaningless now. But what if she had known? Would she have stayed? Maybe. Maybe not. But she didn’t know. And that’s the problem with the legal model - it assumes consent is either fully given or fully absent. Real life doesn’t work like that. Studies show that in many labor trafficking cases - especially among migrant workers - the initial agreement feels real. A man from Cambodia signs up for construction work in Thailand. He’s told he’ll earn $500 a month. He gets $150. He’s told he can quit anytime. He can’t. His passport is gone. His boss threatens to call immigration. He’s been there six months. He hasn’t sent money home. He’s ashamed. He stays. Is he a victim? Yes. Did he consent? He thought he did. The law calls him a victim. But the system still treats him like a criminal if he’s undocumented. He’s stuck between two broken systems: one that says he’s a victim, and another that says he broke the law by crossing illegally.72% of Trafficking Victims Are Immigrants - And the System Blames Them

In the United States, 72% of identified trafficking victims are immigrants. Most are women. Many entered legally on tourist visas and overstayed. Others crossed borders without papers. Either way, their immigration status makes them vulnerable. They’re afraid to report abuse. They’re afraid they’ll be deported. They’re afraid no one will believe them. But here’s the irony: the same laws meant to protect them often punish them. If a woman is trafficked into sex work and arrested, she’s charged with prostitution - even if she was forced. If a man is trafficked into agriculture and reports his employer, he’s flagged for immigration violations. The system doesn’t see him as a victim. It sees him as a rule-breaker. This isn’t accidental. It’s built in. The legal definition of trafficking depends on proving coercion - but coercion is hard to prove when the victim is afraid to speak up. When they’ve been told they’ll be deported. When they’ve been told no one will help them. When they’ve been told they owe money they can’t pay back.

Consent Isn’t a Binary. It’s a Spectrum.

Think of it like this: imagine you’re offered two jobs. One pays $15 an hour with benefits. The other pays $30 an hour, but you have to work 12-hour days, live in a cramped room, and hand over your passport. You’re broke. Your rent is due. You take the second job. Two weeks in, your boss says you can’t leave. You’re trapped. You didn’t sign up for that. But you did sign up for the $30 job. That’s trafficking. But under the law, the moment you said yes to the $30 job, you became a participant in a risky deal - not a victim. Until the coercion starts. But the coercion started the moment you had no other choice. Researchers call this the “consent/coercion seesaw.” At one end: a child kidnapped off the street. At the other: a skilled worker who signs a transparent contract and crosses the border legally. Most cases? They’re in the middle. A woman agrees to work as a nanny because she’s told she’ll get to stay in the U.S. She’s not told she’ll be locked in. She’s not told she’ll be paid $50 a week. She’s not told she can’t call her family. She consented to the job. She didn’t consent to the prison. But the law only sees the second part.Why the System Won’t Change

Why hasn’t the law caught up? Because changing it means admitting something uncomfortable: most people who get trafficked aren’t kidnapped. They’re not lured by strangers. They’re not tricked by fairy tales. They’re making decisions under extreme pressure. And that makes the problem harder to solve. If consent is always invalid when someone is poor, then every low-wage migrant worker could be considered a trafficking victim. That would mean millions of people. Governments don’t want that. It would collapse border controls. It would force countries to rethink labor laws, immigration policy, global inequality. Instead, the system keeps its simple binary: victim or criminal. Safe or guilty. Forced or willing. It’s easier. It’s cleaner. And it lets us ignore the real root causes: poverty, gender inequality, lack of legal pathways for migration, and the global economy that profits from cheap, disposable labor.

What’s Changing - Slowly

Some experts are pushing back. Feminist scholars argue that treating all women in sex work as victims ignores their agency - but also ignores the systems that leave them with no real choices. Others, like researchers studying transgender migrants, point out that the trafficking framework often excludes queer and non-binary people entirely. New studies from 2024 and 2025 are looking at how refugee populations get trapped in trafficking networks. They’re finding that people who flee war zones often end up in situations that look like smuggling - but feel like slavery. Their consent was never real because they had no other options. Some countries are starting to change how they identify victims. Instead of asking, “Were you forced?” they’re asking, “What were your choices?” They’re looking at the whole picture: family pressure, debt, language barriers, lack of legal status, isolation. It’s slow. It’s messy. But it’s starting.The Real Issue Isn’t Consent - It’s Power

The truth is, consent only matters when you have power. If you’re starving, your consent to a job is meaningless. If you’re undocumented, your consent to stay quiet is survival. If you’re a woman in a country where men control your money, your consent to leave with a stranger is desperation dressed up as hope. The Palermo Protocol was meant to protect people. But it’s become a tool to sort them - into victims we care about, and criminals we ignore. The people who need help the most? They’re the ones caught in the gray. The ones who said yes - but only because they had no other option. Until we stop asking whether someone consented, and start asking why they had so few choices - we won’t fix trafficking. We’ll just keep labeling people.Can someone consent to being trafficked?

Legally, no - under the UN Palermo Protocol, consent is irrelevant if force, fraud, or coercion is involved. But in real life, many people agree to situations that later become exploitative. They may consent to a job, a trip, or a relationship, not realizing the full danger. The law treats this as trafficking, but the person’s initial decision is often shaped by poverty, lack of options, or deception - not free choice.

What’s the difference between human trafficking and migrant smuggling?

Smuggling is about moving someone across a border illegally, usually with their consent and for a fee. Trafficking involves exploitation - forced labor, sex work, or servitude - and uses coercion, fraud, or abuse of power. The key difference is intent: smugglers want to move people; traffickers want to control and profit from them. But in practice, the line blurs, especially when people are misled or trapped after arriving.

Why do so many trafficking victims stay silent?

Many are afraid of being deported, arrested, or punished. Others fear retaliation from traffickers. Some believe no one will help them. Many are isolated, don’t speak the language, or are deeply in debt. Some were told they’d be jailed if they spoke out. The system often treats them as criminals first - not victims - which makes reporting even harder.

Are all migrant workers who are exploited victims of trafficking?

Not necessarily. Some workers face poor conditions, low pay, or abuse - but without force, fraud, or coercion, they may not meet the legal definition of trafficking. However, many experts argue that if someone has no real alternatives due to poverty or immigration status, their consent isn’t truly free. The law doesn’t always reflect this reality.

What can be done to improve how trafficking is identified?

Instead of focusing only on whether someone was forced, officials should look at the full context: Was the person in debt? Did they have access to legal work? Were they isolated? Were their documents taken? Are they afraid to leave? These are signs of vulnerability - not just coercion. Shifting the focus from consent to power and choice can help identify more victims and offer real support.