Ottoman Legal Discretion Calculator

How Ottoman Law Responded to Same-Sex Interactions

Ottoman law didn't punish desire, but punished exposure. The legal system focused on public morality, social status, and the violation of gender roles. This calculator helps you understand how different factors affected outcomes.

Enter your parameters and click calculate to see Ottoman legal outcomes

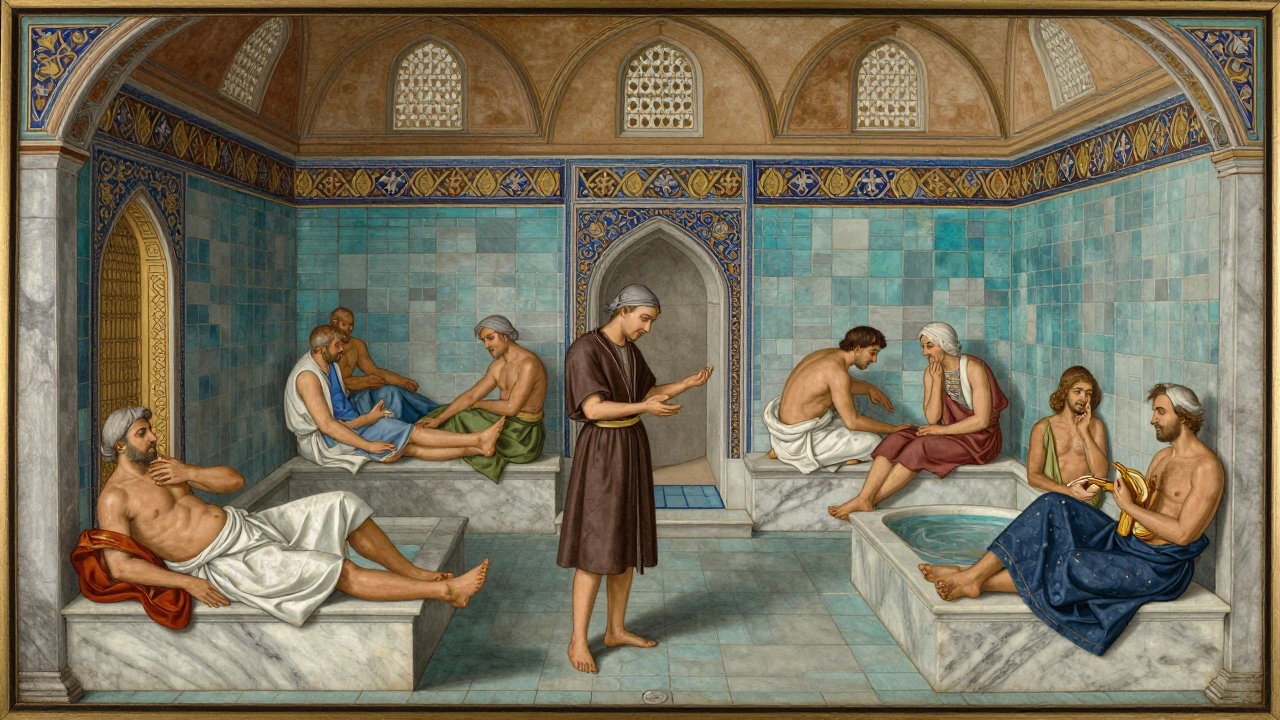

When you think of an Ottoman bathhouse, you might picture steam rising from marble floors, men scrubbing each other’s backs, and the quiet hum of conversation in a warm, humid room. But beneath that surface of hygiene and ritual, something else was happening-something rarely written about, never openly discussed, and carefully hidden from the eyes of law and religion. The male attendants known as telks weren’t just cleaning bodies. In a society where same-sex relations were technically illegal, they moved through spaces where intimacy and power blurred, and where touch became a silent language.

The Hamam as More Than a Bath

Ottoman bathhouses, or hamams, weren’t luxury spas. They were essential public infrastructure. By the late 1600s, Istanbul alone had over 1,200 of them, built next to mosques, markets, and schools. Their main purpose was religious: Islamic law required full-body washing before prayer, and most homes didn’t have running water. But the hamam quickly became a social hub. Men gathered there after Friday prayers. Merchants closed deals over steam. Families celebrated births and weddings. And in the back rooms, away from prying eyes, something more private unfolded.The telks-usually teenage boys or young men from poor families-entered service between ages 12 and 16. They worked for years, scrubbing, massaging, and applying oils to clients. Their job was physically demanding: they had to move quickly between hot and cold rooms, lift heavy bodies, and maintain constant contact. This wasn’t just cleaning. It was intimacy. And in a culture that strictly separated genders and punished open same-sex behavior, that intimacy carried weight.

What the Law Said vs. What Happened

Sharia law, the foundation of Ottoman justice, banned sexual acts between men. Punishments could include fines, public flogging, or even death-depending on the ruler, the era, and whether the act was seen as public or private. But here’s the catch: the law didn’t punish desire. It punished exposure. As historian Leslie Peirce pointed out, discretion was the most important rule. If you kept it quiet, you were rarely touched.Court records from the 1500s show only 17 prosecutions for same-sex acts in Istanbul between 1541 and 1575. By the late 1600s, that number rose to 43-but most of those cases involved coercion, assault, or men who broke gender norms by taking a "passive" role. The telks, often younger and lower-class, rarely faced punishment. Their clients did. If a man was caught acting like the "receiver," he risked being labeled morally weak. The telk? He was just doing his job.

There’s no evidence in Ottoman archives that telks were paid extra for sexual services. No receipts. No witness statements. No contracts. Instead, their wages were fixed-5 to 15 akçe per day, roughly the cost of a loaf of bread. Payment was folded into the bathing fee, not a separate transaction. That’s not how sex work works today. But in a society where money and touch were entangled in complex social hierarchies, it made sense.

European Fantasies and Ottoman Silence

Western travelers in the 1600s wrote wildly different stories. Jean de Thévenot, a French diplomat, claimed telks offered "immodest services" for coin. Others described erotic scenes, half-naked boys, and hidden pleasures. But Ottoman writers? They said nothing. Evliya Çelebi, the famous 17th-century traveler, spent pages describing the architecture, the music, the social life of the hamam-but not a single word about sex.Why the disconnect? Because European observers were looking for something they already believed existed: the "exotic Orient," full of decadent, sensual pleasures. They projected their own fantasies onto a space they didn’t understand. Meanwhile, Ottoman artists painted bath scenes showing men being scrubbed, talking, resting-no erotic poses, no suggestive glances. The truth was mundane. The myth was sensational.

Even 19th-century paintings like Jean-Léon Gérôme’s "The Turkish Bath"-with its naked, reclining men and suggestive lighting-were made in Paris, not Istanbul. They weren’t documentation. They were fantasy. And those images stuck. Today, when people imagine Ottoman bathhouses, they see what Europeans wanted to see, not what actually happened.

Power, Class, and the Limits of Consent

To call telks "sex workers" implies a transactional exchange: money for sex. But the reality was messier. Telks were servants. They had little power. Their bodies were not their own. A client could ask for more than scrubbing. A telk couldn’t say no without risking his job-or worse. Ottoman legal codes warned that a telk who "solicited inappropriate touching" could be flogged. But if a client initiated it? He was the one who faced consequences, if caught.Historian Craig Proxy calls this the "discretion economy." No one talked about it openly. No one needed to. The steam hid everything. The silence protected everyone. A touch might linger a second too long. A hand might brush a thigh. A glance might hold too long. These weren’t always sexual. But in that environment, they could be. And because they were never named, they were never fully controlled.

Modern scholars like Dr. Scott Kugle argue that applying today’s labels-"sex work," "homosexuality," "gay"-to the past is misleading. People then didn’t think of themselves as having a fixed sexual identity. They acted in ways shaped by context: status, age, need, opportunity. A wealthy man might seek closeness with a young telk, not because he was "gay," but because he was lonely, bored, or curious. The telk didn’t choose this life because he was "prostituting himself." He chose it because he had no other options.

The Real Legacy of the Hamam

The hamam wasn’t a brothel. It wasn’t a gay bar. It was a place where people came to wash, talk, rest, and sometimes-when no one was watching-touch in ways that broke the rules. The telks weren’t sex workers in the modern sense. They were young men caught in a system that used their bodies for labor, then punished them if they were seen as too intimate.By the time the Ottoman Empire fell in 1922, the hamam’s role had changed. The new Turkish Republic banned mixed-gender bathing and pushed modern hygiene standards. The old social order vanished. Today, most hamams in Turkey are tourist attractions. The telks are gone. The steam is still there, but the secrets have dried up.

What remains is a quiet lesson: history doesn’t always show us what happened. It shows us what people were allowed to say. And sometimes, the most important truths are the ones buried under silence.

Why This Matters Today

Understanding the telks isn’t just about the past. It’s about how we label people today. When we call them "sex workers," we risk reducing their complex lives to a single act. When we call them "victims," we erase their agency. When we call them "queer pioneers," we force modern identities onto people who never had those words.The telks existed in a world where touch could be a form of survival, not just desire. Where power shaped intimacy. Where silence was the only protection. And where the law looked away-until someone got caught.

That’s not just Ottoman history. It’s a pattern we still see: marginalized people doing necessary work, their humanity hidden behind legal codes, moral panic, and cultural stereotypes. The hamam didn’t create same-sex interactions. It just gave them space to breathe.

Were telks considered sex workers in Ottoman times?

No, telks were not classified as sex workers in Ottoman legal or social terms. They were servants employed to perform bathing and scrubbing services. While intimate physical contact occurred in the private steam-filled environment of the hamam, Ottoman records show no evidence of explicit payment for sexual acts. Sexual interactions, when they happened, were discreet, situational, and rarely documented as commercial transactions. Modern scholars reject the term "sex work" for telks because it imposes today’s categories onto a pre-modern context where identity, consent, and economics operated differently.

Was same-sex activity legal in the Ottoman Empire?

Same-sex sexual acts were technically illegal under Sharia law, with punishments ranging from fines to execution. But enforcement was inconsistent and focused on public behavior, coercion, or violations of gender norms-not private, consensual encounters. Courts rarely prosecuted adult men for discreet same-sex activity, especially if they maintained traditional masculine roles. The real risk was exposure, not the act itself. This created a culture of silence where such interactions occurred but were never formally acknowledged.

Why do Western sources describe Ottoman bathhouses as sexually explicit?

Western travelers and artists in the 17th-19th centuries often projected Orientalist fantasies onto Ottoman culture. They imagined the hamam as a space of exotic decadence, fueled by stereotypes of the "sensual East." Paintings like Gérôme’s "The Turkish Bath" and travelogues by French and British writers exaggerated or invented erotic scenes. Ottoman sources, in contrast, avoided any mention of sexuality, focusing instead on religious, social, and hygienic functions. The discrepancy reflects cultural bias, not historical fact.

Did women have similar roles in the hamam?

Yes, but differently. Women’s hamams had attendants too-often older women or female servants-who helped with bathing, hair washing, and postpartum care. These women also formed tight social networks, hosted bridal rituals, and even acted as mediators in family disputes. While same-sex interactions occurred among women, Ottoman records show far fewer legal cases involving them. This may reflect greater social tolerance for female intimacy, or simply less documentation. Unlike telks, female attendants weren’t typically young men in a liminal social position-they were part of established domestic roles.

How do modern historians know what happened in the hamams?

Historians rely on legal court records, travel accounts, medical texts, and Ottoman tax registers-not on paintings or romanticized stories. Court documents from Istanbul and Aleppo reveal complaints about "improper touching," dismissals of telks for misconduct, and rare prosecutions for public indecency. Art and literature offer clues, but only when cross-referenced with official records. The absence of direct references to sex in Ottoman writings is itself evidence: it shows how deeply discretion was embedded in social norms. No one wrote about it because everyone already knew.

Why is it important not to call telks "sex workers"?

Using the term "sex worker" today implies consent, agency, and a commercial transaction-all concepts that don’t cleanly apply to the telks. They were young, poor, and bound by class and age hierarchies. Their work involved physical intimacy, but it wasn’t chosen as a profession for income. Calling them sex workers flattens their lived reality into a modern label that ignores power, coercion, and cultural context. Better to say they were servants whose work created spaces where discreet intimacy could occur-not because they were selling sex, but because their bodies were the tools of their labor.