They came in the middle of the night, sometimes without warning, sometimes with a knock that sounded like a threat.

For decades, gay bars in America weren’t just places to drink or dance-they were the only safe spaces many LGBTQ+ people had. And yet, every weekend, the risk was real: police could burst in, drag people out by their hair, force them to prove their gender on the spot, and arrest them for the crime of existing. These weren’t random acts. They were systematic. They were legal. And they were designed to humiliate.

In the 1950s and 60s, if you were gay, lesbian, or transgender, you were considered mentally ill, morally corrupt, or a security threat. The U.S. government fired hundreds of federal workers just for being suspected of homosexuality. Bars that served LGBTQ+ patrons were labeled "disorderly houses" by state liquor boards. That meant they couldn’t get liquor licenses. So who ran them? The mafia. And who protected them? Police officers, paid off with cash bribes-up to $3,000 a month, which is over $25,000 today.

But here’s the twist: even when the mafia paid, the raids still happened. The police didn’t shut the bars down-they showed up to make a spectacle. They’d line patrons up against the wall, check IDs, demand proof of gender by forcing people to lift their skirts or pull down their pants. They’d arrest anyone wearing "inappropriate clothing." Women in pants. Men in makeup. Drag queens. Trans women. Young people with nowhere else to go. All of them were treated like criminals.

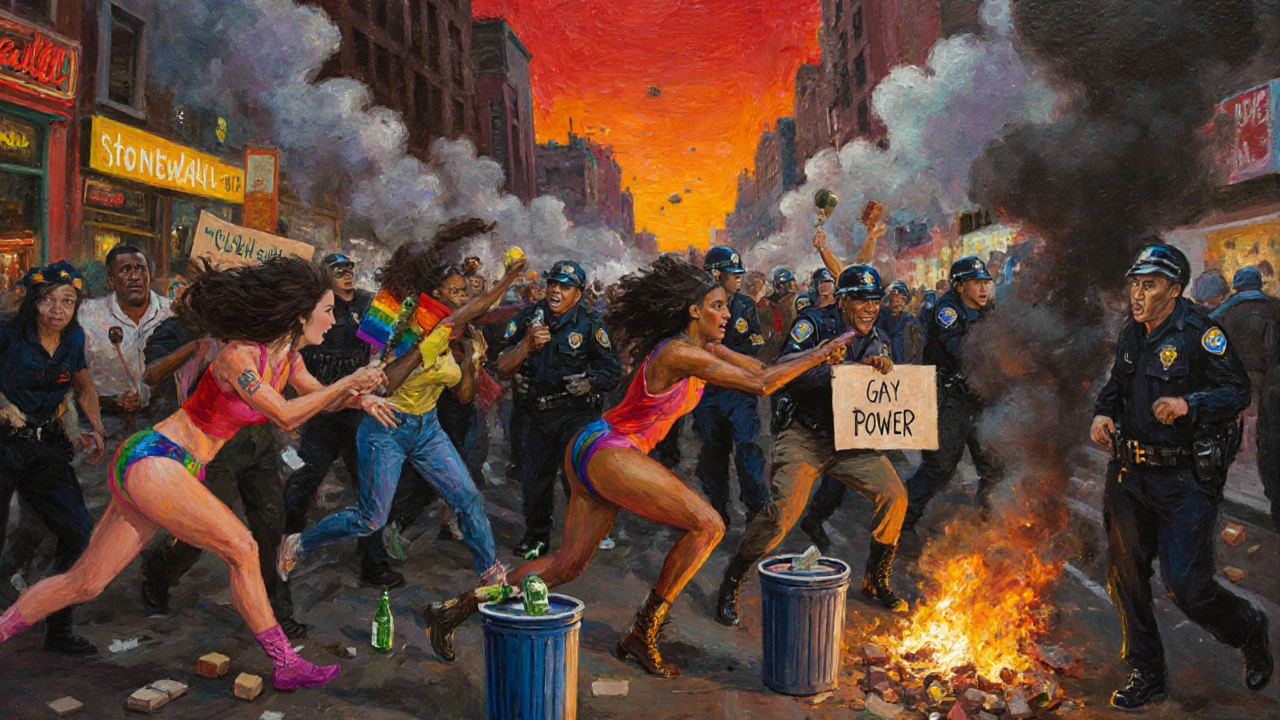

The Stonewall Inn Raid Wasn’t the First-But It Was the Last Straw

On June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City. It wasn’t supposed to be different. The bar had been raided just four days earlier. The mafia usually got a heads-up. This time, they didn’t.

Patrons were stunned. But this time, they didn’t comply.

People started yelling. Someone threw a coin at a cop. Then a bottle. Then a brick. A garbage can rolled into the street. The crowd swelled. People who had spent years hiding-street kids, trans women of color, Black and Latino drag queens-stood their ground. For five nights, they fought back. They didn’t have weapons. They had rage. And they had each other.

Marsha P. Johnson, a Black trans woman who was there, later said: "We were tired of being treated like criminals for loving who we loved. They’d come in and line us up against the wall, check our IDs, make us show our 'female' or 'male' parts depending on how we looked that day."

Stonewall wasn’t the first time LGBTQ+ people resisted. There had been smaller protests before-flyers handed out after raids, quiet meetings in basements, petitions signed in secret. But this time, the resistance spread. The Gay Liberation Front formed. The first Pride march happened a year later, on the anniversary of the raid. And for the first time, people didn’t whisper. They shouted.

After Stonewall, the Raids Didn’t Stop-They Got Worse

Many people think Stonewall ended police raids. It didn’t. It just changed how people responded.

In 1970, police raided The Snake Pit in New York. Over 160 people were arrested. One man, Diego Viñales, jumped out a window to escape. He broke his back. He was Argentinian. He feared deportation. He survived. But he never returned to the U.S.

Decades later, in 2009-exactly 40 years after Stonewall-police raided the Rainbow Lounge in Fort Worth, Texas. No warrant. No warning. They forced 20 people into plastic handcuffs. Two were taken to the hospital with serious injuries. One woman had a panic attack so severe she couldn’t breathe.

In Atlanta, the same year, 48 officers stormed the Eagle, a gay bar. They made 200 patrons lie face-down on broken glass and wet floors. One man, Nick Koperski, said: "I’m thinking, this is Stonewall. It’s like I stepped into the wrong decade."

These weren’t mistakes. They were tactics. Police used SWAT teams, media crews, even the U.S. Border Patrol. In Fort Lauderdale, 100 armed officers showed up to raid a club where no alcohol was even being served. A youth group had rented the space. The sheriff brought his wife.

The Legal System Was the Weapon-And Then It Became the Shield

For years, the law was used to justify the violence. Liquor boards banned service to "homosexuals." Courts upheld arrests for wearing "inappropriate clothing." Police didn’t need warrants. They didn’t need probable cause. They had moral authority-and that was enough.

But after the 2009 raids, something shifted. Community groups demanded investigations. In Atlanta, an independent review found that 24 officers had violated the law. They had detained people without cause. They had lied in reports. The city had to pay damages. It was the first time a police department was held accountable for targeting a gay bar.

These cases became legal blueprints. They helped build the foundation for Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, which struck down sodomy laws nationwide. They fed into Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, which legalized same-sex marriage. And in 2020, Bostock v. Clayton County ruled that firing someone for being gay or trans violated federal civil rights law.

But legal victories don’t erase trauma. Dean Spade, a legal scholar and trans activist, put it plainly: "The tactics of criminalization have evolved but not disappeared."

Who Paid the Price?

Behind every raid, there were names. Faces. Stories lost to history.

Diego Viñales. Frederick William Paez, murdered on the 11th anniversary of Stonewall. Countless others who took their own lives after being humiliated on live TV during a raid. People who lost jobs. Families who disowned them. Kids who ran away and slept on streets because their homes weren’t safe.

And then there were the ones who fought back. Marsha P. Johnson. Sylvia Rivera. Stormé DeLarverie-the butch lesbian who swung a bat at a cop and sparked the first wave of resistance at Stonewall. They weren’t leaders in the traditional sense. They were the most marginalized: trans women of color, sex workers, homeless youth. The people society told to stay quiet.

They didn’t have lawyers. They didn’t have money. But they had courage. And that’s what changed everything.

What Changed-and What Didn’t

Liquor boards no longer call gay bars "disorderly houses." Same-sex marriage is legal. Workplace discrimination is banned in many places. The Stonewall National Monument stands in New York as a tribute.

But raids still happen. Underreporting is still rampant. Trans women of color are still targeted at higher rates than anyone else. The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs recorded 176 hate-related homicides between 2013 and 2018-62% of them were people of color.

And in 2025, the fear hasn’t vanished. When police show up at a queer bar, people still flinch. When someone walks in wearing a dress or a beard, they still look over their shoulder. The law has changed. But the trauma lingers.

What happened in those bars wasn’t just about alcohol. It was about dignity. About the right to exist without fear. The right to be seen-not as a criminal, but as a human.

The fight didn’t end with Stonewall. It didn’t end with marriage equality. It’s still happening-in courtrooms, in city halls, in the quiet moments when someone walks into a bar and wonders if tonight will be the night they’re dragged out.

But now, when that happens, people don’t just disappear. They speak up. They record it. They organize. They remember.

Because the ones who fought back at Stonewall didn’t just change the law.

They changed the story.

Why were gay bars targeted by police in the first place?

Gay bars were targeted because LGBTQ+ people were seen as morally corrupt or a threat to public order. In the 1940s and 50s, government investigations labeled homosexuality as a "security risk." Liquor boards used this to deny bars serving queer patrons licenses, making them illegal. Police then raided these spaces under the guise of enforcing "public decency" laws, even though the same behavior was tolerated in straight bars.

Was the Stonewall uprising the first time LGBTQ+ people resisted police raids?

No. Resistance happened regularly before Stonewall-quiet protests, flyers, legal challenges-but they were rarely documented or sustained. What made Stonewall different was the scale, the duration, and the fact that the most marginalized people-trans women, drag queens, homeless youth-led it. Their anger was visible, collective, and unapologetic, which made it impossible to ignore.

How did the mafia get involved in gay bars?

Because LGBTQ+ people were denied legal access to bars, the mafia stepped in to fill the gap. They ran underground clubs, paid off police to avoid shutdowns, and sometimes even provided protection. But the bribes didn’t stop raids-they just made them predictable. Police would raid to maintain appearances, even when they were paid, because the public expected "law enforcement" to act.

Why did police raids continue into the 2000s?

Even after legal victories, bias and institutional power remained. Police departments still viewed LGBTQ+ spaces as "disorderly" or "high-risk." In 2009, raids in Atlanta, Fort Worth, and Fort Lauderdale showed that outdated attitudes hadn’t disappeared. Officers used excessive force, entered without warrants, and targeted patrons based on appearance-not behavior. The outrage these raids provoked proved that the public was finally ready to demand accountability.

What legal changes came from these raids?

The resistance to raids laid the groundwork for major legal victories. The 2003 Lawrence v. Texas case overturned sodomy laws, citing the right to privacy. The 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges decision legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. And in 2020, Bostock v. Clayton County ruled that firing someone for being gay or trans violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. These were direct results of decades of organizing sparked by police violence.

Are police raids on LGBTQ+ spaces still happening today?

Official raids like those in the 1960s or 2009 are rare now, but harassment continues. Trans women of color are still disproportionately targeted during street stops and in detention. Many LGBTQ+ people avoid bars or public spaces out of fear. Underreporting is high, especially among undocumented and non-binary individuals. The legal protections exist, but enforcement and cultural change lag behind.