Ever wonder why humans have chins? Or why women’s clitorises exist outside the vaginal canal? Or why men experience orgasms even when they don’t reproduce? These aren’t just quirks-they’re evolutionary leftovers that got repurposed. Welcome to the world of spandrels-features that didn’t evolve for their current use, but ended up being useful anyway.

What Exactly Is a Spandrel?

The term comes from architecture. In medieval churches like St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, spandrels are the triangular spaces between arches. They weren’t designed to be decorative. They just happened because you needed arches to hold up a dome. Later, artists painted mosaics on them. The spandrels weren’t made for art-they became art by accident. Evolutionary biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin borrowed this idea in 1979. They argued that not every body part evolved because it gave an advantage. Some are just side effects-byproducts-of other changes. Think of them as evolutionary accidents that got lucky. A spandrel isn’t an adaptation. It’s not shaped by natural selection for its current job. It’s a structural side effect. But here’s the twist: once it exists, nature can use it. That’s called exaptation. A feature evolves for one reason, then gets reused for another. The spandrel didn’t ask for this. It just showed up-and got drafted.The Human Chin: A Spandrel in Your Face

Humans are the only primates with chins. All other apes have sloping jaws. So why do we have this bony protrusion under our lower lip? Some thought it helped with chewing. Others said it’s for speech. But none of those explanations hold up. The chin doesn’t improve bite force. It doesn’t help articulate sounds. In fact, it makes our jaws weaker. A 2000 study in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology looked at how our faces changed over time. As human skulls shrank-probably due to dietary shifts and less need for powerful jaws-the lower jaw didn’t shrink evenly. The front part stuck out. That bump? It wasn’t selected. It was forced by the way our bones grew. A spandrel. And yet, here it is. We’ve made it part of our identity. In some cultures, a strong chin signals dominance. In others, it’s considered attractive. The chin didn’t evolve to be admired-but now it is. That’s exaptation in action.Female Hyenas and the Pseudo-Penis

Female spotted hyenas have a clitoris so large it looks like a penis. It’s fully erectile, can urinate and mate through it, and even gives birth through it. It’s one of the most bizarre anatomical oddities in the animal kingdom. At first glance, it seems like a mistake. But it’s not. Female hyenas need high levels of testosterone to dominate their social groups. That testosterone doesn’t just make them aggressive-it also masculinizes their genitalia. The clitoris swells because the same hormones that build muscle and aggression also affect tissue development. This trait didn’t evolve to be a penis. It evolved because powerful females survived better. The enlarged clitoris? A side effect. A spandrel. And yet, it became central to their social structure. Males have to carefully navigate this anatomy to mate. Females control reproduction through it. The spandrel didn’t plan this. But evolution did.

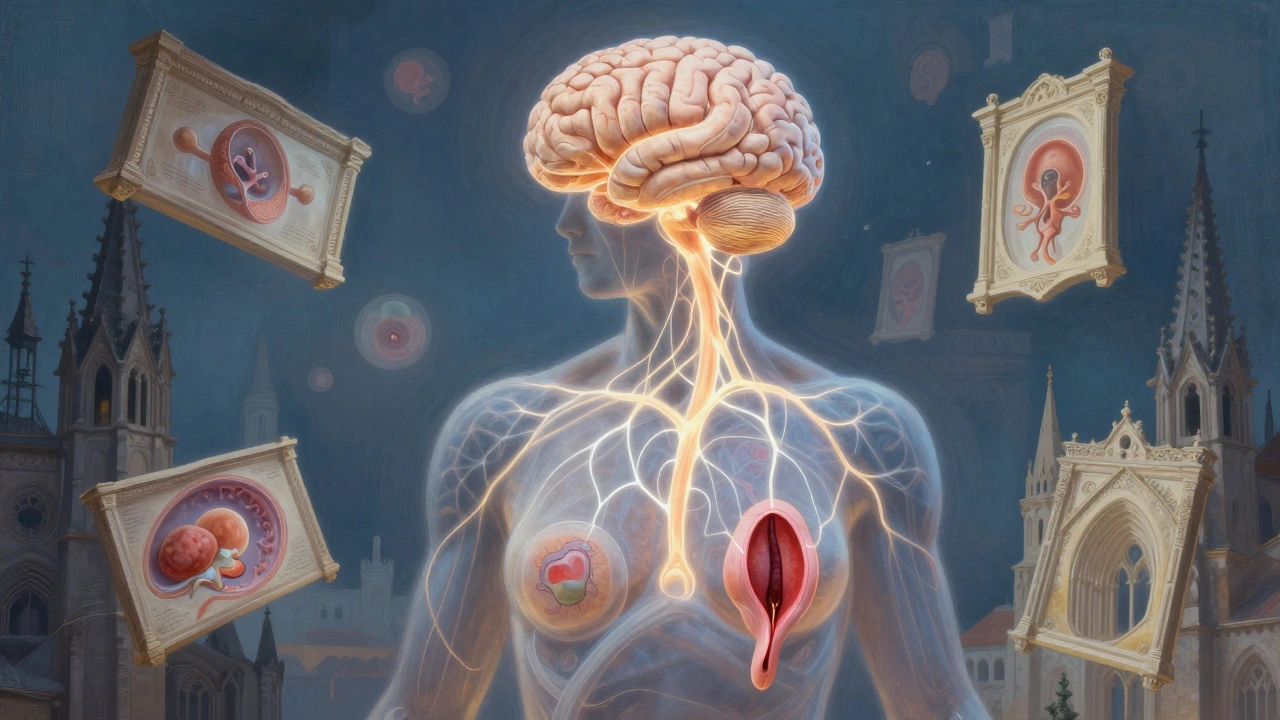

The Human Clitoris and Orgasm

Here’s where it gets personal. The clitoris exists because it’s part of the same developmental pathway as the penis. In the womb, all embryos start with the same genital blueprint. Whether it becomes a penis or a clitoris depends on hormones. The clitoris isn’t there for reproduction. It’s not needed for pregnancy or childbirth. It’s there because it’s the female version of a structure that *is* used for reproduction in males. In males, orgasm triggers ejaculation-directly linked to reproduction. In females, orgasm has no clear reproductive role. Sperm doesn’t need it. Fertilization happens whether she climaxes or not. So why does it exist? The answer? It’s a spandrel. The neural wiring for orgasm evolved in males because it made reproduction more likely. That same wiring got turned on in females because the embryonic structures are shared. It’s not a mistake-it’s a consequence. And yet, here’s the twist: female orgasm is incredibly common. It’s pleasurable. It strengthens bonds. It’s linked to pair bonding, stress reduction, and even better sleep. Evolution didn’t select for female orgasm. But once it was there, it became useful. That’s exaptation again. This isn’t just theory. A 2019 study in Evolution found that female orgasm frequency correlates with relationship satisfaction, not fertility. It’s not about babies. It’s about connection. The spandrel became a tool for intimacy.Male Orgasm: A Spandrel That Works Too Well

Men have orgasms because they trigger ejaculation. That’s adaptive. But here’s the catch: men can orgasm without ejaculation. They can orgasm without sex. They can orgasm while sleeping. They can orgasm after vasectomy. They can orgasm while masturbating to fantasies that have nothing to do with reproduction. The mechanism is so powerful, it overrides logic. A man can climax while thinking about something completely unrelated to mating. Why? Because the nervous system doesn’t care about context. It just responds to stimulation. The ability to orgasm evolved because it made reproduction more likely. But now, it’s detached from reproduction entirely. It’s a spandrel that got hijacked by culture, media, and fantasy. We use it for pleasure, stress relief, even self-soothing. It’s no longer just a reproductive tool. It’s a universal human experience.Why This Matters

The spandrel concept forces us to stop assuming every trait has a purpose. We’re wired to think everything exists for a reason. But biology doesn’t work that way. Features can be accidents that turn into advantages. Orgasm isn’t just about reproduction. The chin isn’t just for looks. The hyena’s clitoris isn’t just a deformity. Understanding spandrels helps us stop blaming bodies for not being “designed” perfectly. It helps us see why female pleasure exists even if it’s not necessary for reproduction. It explains why men have such intense orgasms even when they’re not trying to make babies. It also helps us be kinder to our own bodies. If you’ve ever felt weird about your anatomy-too sensitive, too responsive, too strange-know this: you’re not broken. You’re an evolutionary accident that turned out beautifully.

How Do Scientists Prove Something Is a Spandrel?

It’s not easy. You can’t just say, “This doesn’t seem useful.” You need evidence. One method is fossil history. If a feature appears before its supposed function, it’s likely a spandrel. The shoulder hump of the giant Irish deer existed long before it was used for sexual display. The hollow space in coiled snail shells existed before it was used to protect eggs. Another method is comparative anatomy. If a trait shows up in species that don’t use it for the same purpose, it’s probably not an adaptation. The clitoris appears in all female mammals-even those that don’t orgasm. That suggests it’s a shared developmental byproduct, not a selected trait. The third method is developmental biology. If a trait emerges from a shared embryonic pathway, it’s likely a side effect. The clitoris and penis come from the same tissue. The chin emerges from jawbone reshaping. These aren’t designed-they’re built.What Critics Say

Not everyone buys it. Richard Dawkins called spandrels “adaptations we haven’t figured out yet.” He argued that if a trait exists, natural selection probably shaped it-even if we don’t see how. But that’s the problem with adaptationism. It assumes every trait must have a purpose. That’s like saying every shadow on the wall was painted on purpose. Sometimes, the shadow is just from a window. You don’t need to explain the shadow-you need to explain the window. The spandrel concept doesn’t deny natural selection. It just says: not everything is chosen. Some things are just… there. And that’s okay.What This Means for You

If you’ve ever felt like your body doesn’t make sense-especially when it comes to pleasure, desire, or anatomy-you’re not alone. Evolution didn’t design you to be efficient. It cobbled you together from old parts, accidents, and leftovers. Your ability to feel pleasure? That’s a spandrel. Your capacity for emotional connection through touch? That’s a spandrel. Your chin? A spandrel. Your orgasm? A spandrel. And that’s beautiful. You’re not a perfectly engineered machine. You’re a living archive of evolutionary accidents that somehow turned into meaning. The next time you feel pleasure, remember: it didn’t evolve to make you happy. It evolved because of something else. But now? It’s yours. And that’s more powerful than any adaptation ever could be.Are spandrels the same as vestigial organs?

No. Vestigial organs are features that used to be useful but have lost their function-like the human appendix or tailbone. Spandrels are features that never had a function to begin with. They emerged as side effects and were later co-opted. A spandrel isn’t broken-it never had a job to begin with.

Can a spandrel become an adaptation?

Yes-that’s called exaptation. A spandrel is the original byproduct. Once it’s used for a new purpose and natural selection starts shaping it for that purpose, it becomes an adaptation. The human chin started as a spandrel. Now, in some cultures, it’s selected for in mate choice. That’s exaptation turning into adaptation.

Why is the female orgasm considered a spandrel?

Because it doesn’t improve reproductive success. Women can conceive without orgasm. The clitoris and orgasmic response evolved as a byproduct of male orgasm development in the womb. Since the same embryonic tissue forms both, female orgasm is a side effect-not a selected trait. Its current role in bonding and pleasure is a later co-option.

Do all animals have spandrels?

Almost certainly. Every organism is built from existing genetic and developmental blueprints. Changes in one part often force changes in others. The hollow space in snail shells, the human chin, the male nipple-all are likely spandrels. They’re not rare. They’re universal.

Is the concept of spandrels still accepted today?

Yes. A 2025 survey of evolutionary biologists found 92% consider spandrels a fundamental concept. While debate continues over how common they are, no serious scientist denies their existence. The key insight-that form doesn’t always equal function-is now central to evolutionary biology.