The Mann Act wasn’t passed to stop human trafficking. At least, not the kind we think of today. When Congress passed the White-Slave Traffic Act in 1910, it was responding to a panic that had little to do with forced prostitution and everything to do with race, fear, and control. The law made it a crime to transport a woman across state lines for what lawmakers called "any other immoral purpose." That phrase-vague, sweeping, and loaded-became a weapon. It turned consensual relationships into federal crimes. It targeted Black men in interracial relationships. And it laid the groundwork for how the federal government could police private behavior under the guise of commerce.

What the Mann Act Actually Did

The Mann Act, officially the White-Slave Traffic Act of 1910, made it illegal to transport any woman or girl across state or international borders for "prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose." The punishment? Up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine-roughly $150,000 today. The law didn’t require proof the woman was forced, tricked, or underage. It didn’t even require proof she was a prostitute. All prosecutors needed was evidence she crossed a state line with a man, and that their relationship didn’t fit the moral standards of the time.

The law was built on the Commerce Clause, giving Congress power over interstate travel. That legal trick let the federal government step into bedrooms and relationships that had always been handled by local authorities. It didn’t matter if the woman was an adult, willing, or even married to the man. If she traveled with him and their relationship was deemed "immoral," he could be locked up.

The Jack Johnson Case: When the Law Became a Racial Weapon

Jack Johnson wasn’t just a boxer-he was the first Black heavyweight champion of the world. And in 1910s America, that made him dangerous. His relationships with white women were seen as a threat to racial hierarchy. In 1912, he began dating Lucille Cameron, a white woman from Chicago. The next year, federal agents arrested Johnson under the Mann Act, claiming he transported her across state lines for "immoral purposes."

The truth? Cameron was his girlfriend. She wasn’t a prostitute. She wasn’t coerced. She even wrote letters to the court defending him. But none of that mattered. The jury convicted him in 1913. Johnson fled the country, living in exile for seven years in Canada, Europe, and South America. He returned in 1920 to serve a year in prison. His case wasn’t an exception-it was the rule. The Mann Act became a tool to punish Black men for loving white women during the Jim Crow era.

Johnson was pardoned by President Donald Trump in 2018, over a century after his conviction. The pardon didn’t erase the law’s legacy-it just acknowledged how badly it had been used.

How the Law Turned Consensual Sex Into a Crime

In 1913, the Supreme Court made it official: consensual sex could be prosecuted under the Mann Act. In Caminetti v. United States, two men-Drew Caminetti and Maury Diggs-were convicted for taking their mistresses from Sacramento to Reno. They weren’t trafficking them. They weren’t forcing them. They were just having affairs. The women were adults. They went willingly. But the Court ruled that "immoral purpose" included extramarital relationships. That decision opened the floodgates.

By the 1920s, Mann Act prosecutions were common. Men were arrested for driving their girlfriends across state lines. Women were sometimes charged as accessories. The law didn’t care about consent. It cared about social order. And in that era, social order meant keeping white women "safe" from Black men, immigrants, and anyone who didn’t fit the mold of respectable, Protestant, heterosexual life.

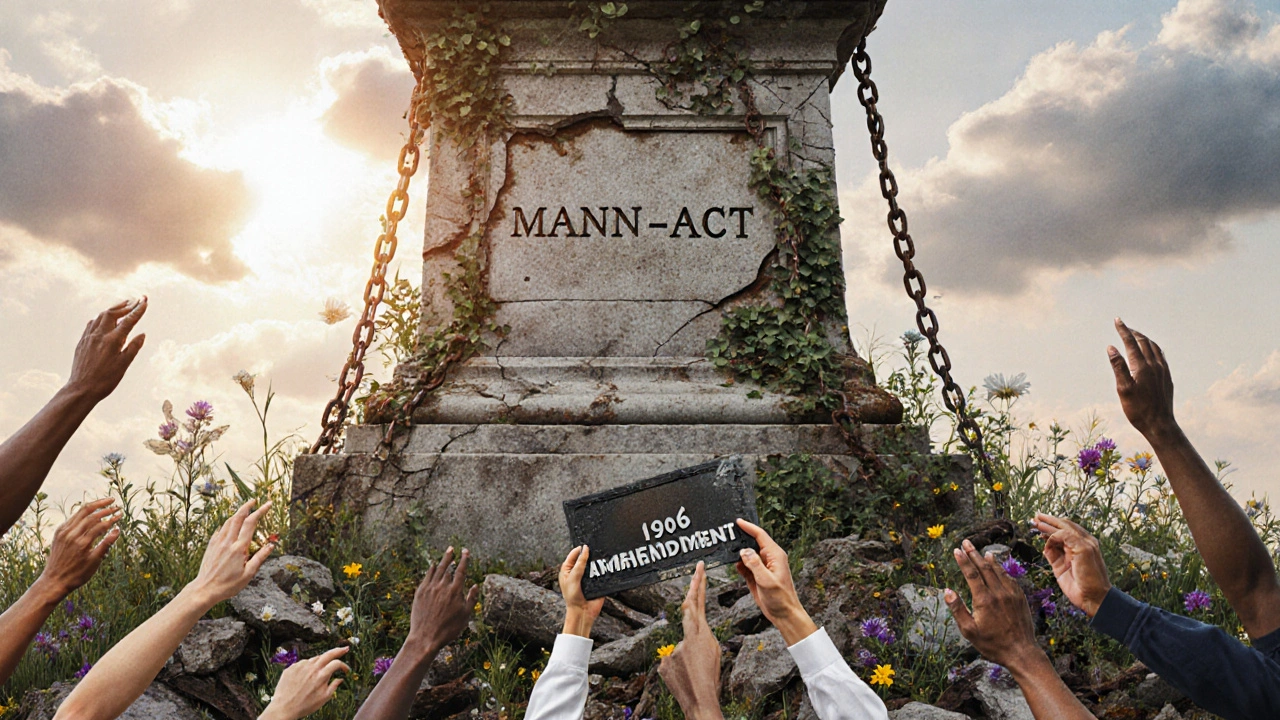

The 1986 Amendment: A Narrowing, Not a Repeal

By the 1970s, public opinion had shifted. The law was seen as outdated, even absurd. In 1986, Congress finally fixed the worst part: the phrase "any other immoral purpose." It was replaced with "any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense." That meant the law could no longer be used to punish adultery, cohabitation, or consensual relationships.

Now, prosecutors had to prove the sex was illegal-like involving minors, prostitution, or incest. That narrowed the law dramatically. But it didn’t kill it. The Mann Act still exists. It’s still on the books. And today, it’s used mostly in cases involving child sex trafficking, often alongside the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000.

How the Mann Act Compares to Modern Anti-Trafficking Laws

Modern trafficking laws focus on force, fraud, or coercion. The TVPA, passed in 2000, requires prosecutors to show the victim was exploited, not just traveling with someone. The Mann Act didn’t need any of that. All it needed was movement across a state line and a judge’s idea of what was "immoral."

Today, federal prosecutors use the Mann Act in fewer than 250 cases a year-down from over 300 in 2010. Most involve minors. Some involve adults in illegal sexual activity. But the days of locking up men for dating white women are over. The law’s scope is now limited, but its shadow remains.

Why the Mann Act Still Matters

The Mann Act wasn’t just a bad law. It was a mirror. It showed how quickly fear can turn into legislation. It showed how federal power can be stretched to control personal behavior. And it showed how easily moral panic can be weaponized against marginalized groups.

It was passed during the Progressive Era, a time of sweeping reforms. But while progressives pushed for child labor laws and women’s suffrage, they also pushed laws like the Mann Act to police sexuality and race. The same people who fought for social justice also helped create tools of racial control.

Today, the Mann Act is a reminder that laws meant to protect can also oppress. It’s proof that vague language in legislation doesn’t just create loopholes-it creates weapons. And it’s a warning: when we let moral outrage drive policy, we risk punishing the innocent to satisfy the fears of the powerful.

What Happened to the Women?

Most histories focus on the men prosecuted under the Mann Act. But what about the women? In the early years, women could be charged as accessories. If a woman traveled with a man and authorities decided their relationship was "immoral," she could be arrested too. Some were pressured to testify against their partners. Others were sent to reformatories under the guise of "rescue."

There’s little record of how many women were prosecuted. Most were poor, working-class, or women of color. Their voices were rarely preserved. We know about Lucille Cameron because she was connected to a famous man. But what about the hundreds of others who disappeared into court records with no names, no stories, no defense?

Was the Mann Act really used to target interracial relationships?

Yes. The law was frequently used to prosecute Black men in relationships with white women during the Jim Crow era. The most famous case was boxer Jack Johnson, convicted in 1913 for dating Lucille Cameron, a white woman. Prosecutors didn’t need to prove coercion or prostitution-just that they traveled together. Similar cases happened across the country, especially in the South and Midwest, where racial tensions were high.

Did the Mann Act stop human trafficking?

Not really. There’s little evidence it reduced forced prostitution. Instead, it was used to criminalize consensual relationships. Modern anti-trafficking laws like the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 focus on force, fraud, and coercion-which the Mann Act never required. Today, the Mann Act is rarely used for trafficking cases and mostly applies to child exploitation.

Is the Mann Act still in effect today?

Yes. The law still exists under 18 U.S.C. §§ 2421-2424. But after the 1986 amendment, it can no longer be used to prosecute consensual adult relationships. Today, it’s primarily used in cases involving minors or illegal sexual activity, often alongside the TVPA. Prosecutors must now prove the sexual activity was criminal under state or federal law.

Why did Congress pass the Mann Act if it wasn’t about trafficking?

The law was passed during a moral panic over "white slavery," a term used to describe fears that white women were being kidnapped into prostitution. But historians agree this crisis was largely imagined. It was fueled by racism, xenophobia, and anxiety over immigration and changing gender roles. Politicians used the law to appear moral and tough on crime-even though it targeted consensual behavior more than trafficking.

How did the Mann Act expand federal power?

Before the Mann Act, regulating personal behavior like relationships or sexuality was a state issue. The law used the Commerce Clause-the power to regulate interstate commerce-to justify federal intervention in private conduct. The Supreme Court upheld this in Caminetti v. United States, setting a precedent that allowed Congress to use commerce power for moral regulation. This helped pave the way for future federal laws that intruded on personal life.

What’s Next for the Mann Act?

Some legal scholars argue it should be repealed. With the TVPA and PROTECT Act covering trafficking and child exploitation more effectively, the Mann Act feels like a relic. Others say it’s still useful as a backup tool in complex trafficking cases where interstate movement is clear.

But its real value today isn’t in prosecution-it’s in education. The Mann Act teaches us how laws can be twisted by fear. How language can be weaponized. How justice can be distorted by prejudice. It’s not just history. It’s a lesson in how power works.